There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen,’ observes Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known by his alias Lenin, the founder of Soviet Russia. Long confined to the margins of Russian politics, where he watched the obstinate endurance of an anachronistic tsardom and the fratricide of European socialists at the turn of the twentieth century, Lenin knew the twists and turns of history intimately—most especially, its dizzying compression in revolutionary times.

Violently supplanting a centuries-old monarchy at the tail-end of the First World War, his Bolshevik utopia lasted only decades, first collapsing under the weight of Stalinist repression and, in the second half of the century, suffering irredeemable sclerosis under its placid successors.

Contemporary China has self-consciously reinvented itself in opposition to the Soviet experience. While Mao Zedong dismissed Lenin’s heirs as imperialist wolves in proletariat clothing, his successors painstakingly sought to avoid Soviet stagnation and, more crucially, Gorbachev’s disastrous—in their eyes—gambit of political liberalisation.

On his deathbed, Deng Xiaoping was asked about his greatest legacy. His reported response was both astonishing and understandable. Contrary to conventional expectations, it was not Deng’s decision ‘to open up the [Chinese] economy’, for which he is best known, but instead that he ‘resisted the temptation to go all the way and open up also the political life to multi-party democracy’.

This was no small matter, since, as Slavoj Zizek writes, ‘the tendency to go all the way was pretty strong in some Party circles and the decision to maintain Party control was in no way preordained’.

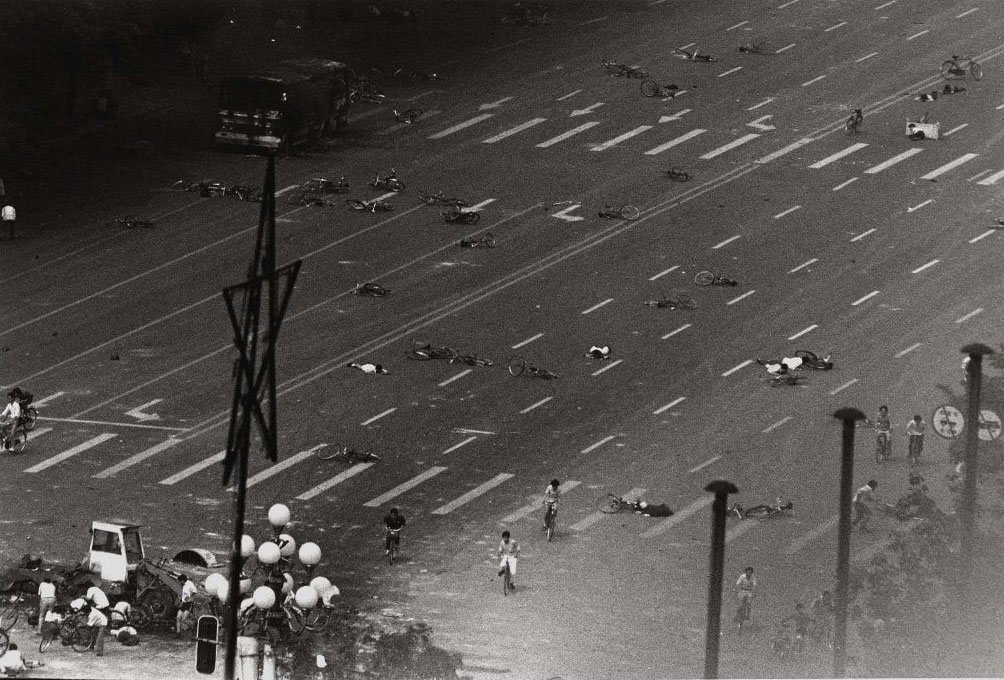

And this is precisely the context within which the communist regime’s brutal response the pro-democracy Tiananmen protests in 1989 should be understood. Both the West, and likely the brave students, misunderstood Zhongnanhai’s political calculus.

In stark contrast to Gorbachev and reformist forces in the Soviet bloc, who advocated a perestroika and glasnost agenda of comprehensive liberalisation, Mao’s heirs meticulously exploited economic liberalisation for national development while largely shunning any meaningful democratic opening.

Despite the best efforts of liberals such as Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang to push for political liberalisation, the Chinese communist insiders ultimately coalesced around violent crackdown on any democratic dissent.

As leaked internal documents, the ‘Tiananmen Papers’, illustrate, the primary consideration of the Chinese Communist Party was (and remains) regime survival. At its very core, there was hardly any ideological receptivity to genuine political opening beyond the limited circle of liberal reformists, who were purged following the Tiananmen protests.

Andrew Nathan, a China expert, notes that the Tiananmen episode was ‘a sign of what was to come in China as, in later decades, the party resorted to ever more sophisticated and intrusive forms of control to combat the forces of liberalisation’.

More importantly, it also highlighted the communist regime’s willingness to risk international isolation, and even serious economic reversal, if necessary. The West initially responded with tough diplomatic language and targeted sanctions, but it didn’t take long before the Clintonite liberals passionately advocated for greater economic engagement with China.

The lesson Beijing took from the episode was this: you can get away with brutal crackdowns and human rights violations, and that the West is either naive or cynical enough eventually to welcome China back into the fold of globalisation.

Hence the two decades of full-spectrum economic engagement with China, beginning in late-1990s and slowing to a halt with Donald Trump’s trade war today. China comfortably sailed on the crest of US-led economic globalisation and, in the process, rapidly transformed into the greatest threat to Western hegemony since the dawn of modernity.

Ideologically, these were Lenin’s ‘decades where nothing happens’ and, worse, when the West behaved as if nothing happened during the 1989 students protests in Beijing and more than hundred cities across the country.

And yet, history has its way of punishing geopolitical amnesia and ideological complacency. The Hong Kong protests, also led by students, seem like Lenin’s ‘weeks where decades happen’. The large-scale mass gatherings—a most potent expression of democratic resistance to Beijing’s authoritarian shadow—have laid bare the universality of what Alexis de Tocqueville characterised as an irresistible ‘social impulse’ for democracy.

Unfortunately, the spectre of the Tiananmen crackdown, which has been faithfully commemorated by Hongkongers, is once again haunting us. After showing a degree of tolerance for dissent—not too dissimilar from the initial weeks of the pro-democracy protests in 1989—the communist regime seems to be reaching for the hammer of repression.

The ‘national security law’ recently passed by the National People’s Congress is likely a prologue to a more violent crackdown in Hong Kong. Drafted with zero consultation with the people of Hong Kong and their representatives, the new measures pave the way for China’s feared ministries of Public Security and State Security to directly participate in any campaign of repression.

Back in 2015, the NPC defined terrorists as ‘whoever propagates terrorism or extremism by way of preparing or distributing books, audio and video materials or other items that propagate terrorism or extremism or by way of teaching or releasing information’. It’s almost certain that similarly amorphous definition would be applied in Hong Kong’s case, which would likely include any act against Chinese ‘state power’.

Today, unlike in 1989, the US has lost much of its moral and geopolitical capital, while much of the world is slipping into economic recession and social upheaval amid the coronavirus pandemic. Meanwhile, Beijing boasts a mighty military and a gigantic economy, which is expected to recover ahead of its peers.

Thus, the communist regime could once again calculate, and with greater self-confidence and strategic certainty, that it can crack down heavily on democratic dissent and get away with it. Given Hong Kong’s status as a global hub, however, this could trigger a chain of unintended consequences, further crystalising a liminal global resistance to China’s bid for hegemony.

During his historic speech at the United Nations in 1974, Deng Xiaoping warned, ‘If one day China should change her colour and turn into a superpower, if she too should play the tyrant in the world, and everywhere subject others to her bullying, aggression and exploitation, the people of the world should identify her as social-imperialism, expose it, oppose it and work together with the Chinese people to overthrow it.’ That fateful day may have arrived already.

![]()

- Tags: China, Free to read, Notebook, Richard Heydarian