If you’ve followed what’s happened in Myanmar the past two years, the photos of the Assumption Church in Chan Thar village probably won’t shock you. They show its 129-year-old belltower blackened by upward licks of smoke, a mound of grey ash at its entrance, smoke from the remains of a nearby convent rising against a cobalt sky. When soldiers set fire to the compound last month, it was only the latest in a cascade of desperately cruel acts, all with the aim of crushing resistance to the coup of 1 February 2021. They beheaded two men in the same Sagaing village last June.

Beheadings, shootings, beatings, airstrikes: horrors on near daily display for anyone wanting to look, alongside less gruesome strategies of arrest and harassment designed to punish civil disobedience and silence expressions of online and offline dissent. Religious buildings have been key targets: churches but also Buddhist monasteries, notwithstanding the generals’ claim to serve as Buddhism’s protector. Fire has been a key tool, as it was during the 2017 campaign against the Rohingya, which the US last year said constituted a genocide.

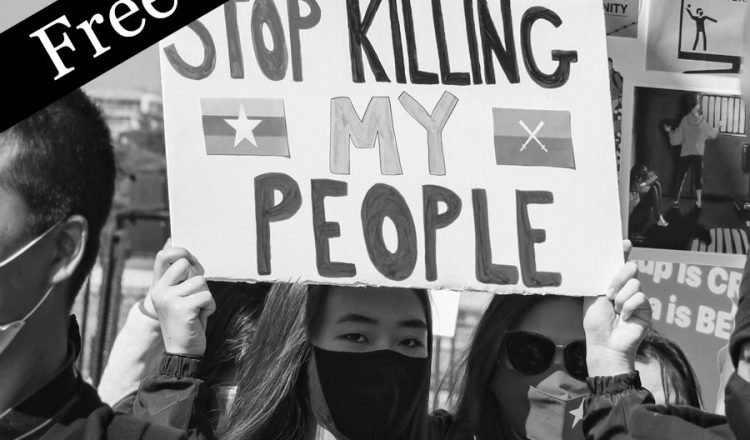

Satellite images of scorched villages show the situation most clearly. Some 30,000 structures are thought to have been burned since the coup—from Karen State in the east to Chin State in the west, where airstrikes in January sent hundreds fleeing across the mountainous Indian border. Just as this Christian-majority region has been a stronghold of the resistance, so the Chin diaspora have been key advocates labouring to raise Myanmar’s plight to international consciousness. In the run-up to the recent passage through Congress of the US Burma Act, which promises deepened sanctions and expanded aid, Chin churches across the American heartland showed videos instructing congregants on how to lobby their local representatives.

Catholic doctrine on the Assumption teaches that, at the end of her life, Mary was taken up—assumed—into heaven, her body and soul intact. There were Old Testament precedents; on account of his zeal, the prophet Elijah was taken up in a chariot of fire. Mary’s assumption is said to anticipate the future salvation of humanity. In Myanmar, many have taken salvation into their own hands. In 2021, once the initial waves of protest were met with bullets from the military, or Sit-Tat, and indifference from an international community that some hoped would be their saviour, the Spring Revolution took a guerrilla turn.

Across the country hundreds of People’s Defence Force (PDF) groups have been at war with the Sit-Tat ever since. Sagaing has been a hotbed, east of the Chin Hills and west of Mandalay. Once spared much of the cruelty that the Sit-Tat has for decades inflicted on Myanmar’s borderlands, this central Anya (or “upstream”) region is now also a target for collective punishment.

“They arrived around 8 a.m. on Saturday,” one Chan Thar resident told The Irrawaddy. “They torched houses the whole day. They then stayed in the church compound, and left this morning after torching the church.” It was the soldiers’ fourth arson attack in the village since last May, reducing its houses from 600 to fewer than forty. Its mostly Catholic population descend from Portuguese mercenaries and traders who arrived in the sixteenth century, centuries before the three Anglo-Burmese wars that brought Burma under the Raj.

The most famous of these Portuguese, the Lisbon-born Filipe de Brito, came via Goa and served the King of Arakan with such distinction that he was made Governor of the growing shipping port of Syriam—now Thanlyin, a township across the Bago River from today’s Yangon. Other Portuguese mercenaries joined him, as did Jesuit priests. Conversions followed. In 1602, de Brito went out on his own, coming into conflict not only with his former Arakan master but with the King of Ava, Anaukpetlun.

De Brito’s troops shared something of the Sit-Tat’s approach to religion, looting pagodas, destroying Buddha images, and melting down bells for weapons. When Anaukpetlun captured Syriam in 1613, his men impaled de Brito and marched hundreds of surviving Portuguese prisoners north to Ava. It was their descendants who, after generations of intermarriage, built the Assumption Church in 1894. Also a descendant is Cardinal Charles Bo, the current Archbishop of Yangon. Criticised for his ongoing dealings with the junta, Bo’s hosting of the coup leader Min Aung Hlaing at a recent Christmas Mass, only a month after soldiers burnt houses in the Cardinal’s own home village, came as little surprise.

More surprising perhaps are the findings of a recent report detailing the extent to which the Sit-Tat has become self-sufficient in the domestic production of many of the weapons it uses against its own people, as well as the degree to which this production is relying on raw materials supplied by companies from a dozen foreign countries. “The West, in lieu of arming the resistance,” one analyst wrote of the report’s implications, “could increase pressure on its allies in Taiwan, Ukraine, Israel and Singapore to end all support.”

From Filipe de Brito to Min Aung Hlaing, violence in Myanmar has long had an outside: connections to circuits of capital and commerce—and, occasionally, concern—extending from its Anya heartland to its maritime and mountain borders, and far beyond.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Michael Edwards, Myanmar