San Po Kong is one of Hong Kong’s most “local” places, with a fifty-year history as an industrial area. Purposely built, in its prime it was a hive of factories, car workshops and print houses. Each night, its street-side restaurants would feed thousands of workers and their families — locals and mainlanders alike.

In the 1990s, however, as Hong Kong transformed from a manufacturing and export centre to a financial services centre, the industrial heart of San Po Kong began to move north. Over the years, the empty units and low rents have attracted art galleries, recording studios, coworking spaces, fitness centres, offices, cake kitchens, breweries and display rooms, among other ventures. Many of the area’s buildings have been renovated for commercial use; San Po Kong has been reassigned by the government as a future business centre in Kowloon East. On the main street, cafes and fancy bakeries are opening where ten years ago there were only cha chaan teng.

I first came to San Po Kong in 2009, when I started editing the literary magazine Fleurs des lettres. The area was still largely industrial, but there were only a few local eateries on the main street, serving fish balls, milk tea and instant noodles. Most of the buildings were old, high with the smell of worked metal and wood. Trucks and vans packed the damp alleys, leaving office workers, like me, to squeeze past them to get to work.

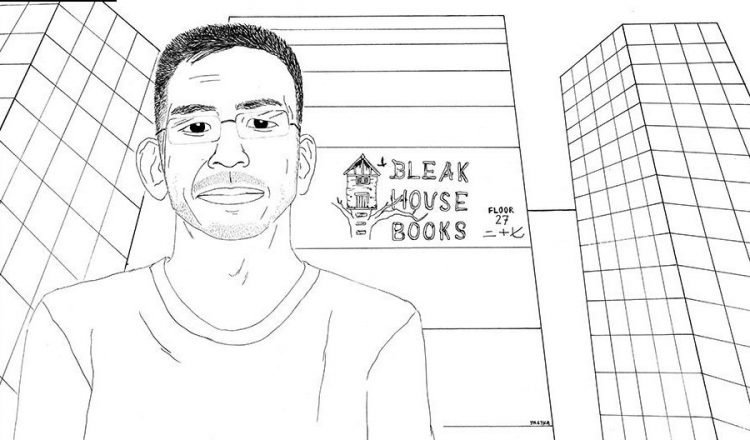

Only recently have glass-paned commercial buildings begun to replace the factories and godowns. Now, on Pat Tat Street, Bleak House Books occupies the twenty-seventh floor of a refurbished office building. Named after the Dickens novel, the bookshop opened last year, after more than three months of preparation and shopfitting. I had seen Albert Wan, the owner, setting up the wooden shelves, pricing and placing every book according to category.

As a bookstore selling English-language books, Bleak House does not necessarily speak directly to the local community, most of whom speak Cantonese and read Chinese. Yet the forty-year-old Wan, a former civil rights lawyer from Atlanta, Georgia, chose to drop anchor here and set up his first bookshop.

“My wife and I didn’t know San Po Kong before we came here,” Wan said. “But we didn’t want our shop to be inside a fancy arts building. This is not the best place to be in terms of retail business, but we like it.”

Disillusioned with the US government and the country’s legal system, Wan quit his fifteen-year-old law practice and settled in Hong Kong with his wife, who teaches here. He started selling books on weekends, at a stall in one of city’s English-speaking residential areas, but he soon felt the need to have a stable space of his own. “A bookshop is not just a retail business but a business that can engage with and be part of the community,” he said. “A bookshop can do that.”

Bleak House is stocked with rare signed copies of English classics, translations of Chinese and Japanese literature, and a variety of thrillers, detective stories, art books, comics, and children’s books, among other genres. It tries to balance the tastes of well-read readers of English with those of local readers who read English to various degrees. One can find books from inspiring independent publishers alongside well-known classics and New York Times bestsellers. “We like to curate for our customers,” Wan said, “so they will be inspired by something new, something they didn’t know they wanted.”

Bleak House also hosts book clubs, poetry readings and evening talks, drawing readers to this former industrial area, which is often deserted outside office hours. The shop is more spacious than most others in Hong Kong, with armchairs that offer a relaxing place to read. “Many shops are cluttered, putting out as many things as they can,” Wan said. “We don’t want our shop to be like that. But this goes against the ‘Hong Kong way’, in which profit is given priority.

“Running a bookstore is hard — it’s not easy to make a profit. We hope to cover expenses, to maintain a certain level of revenue. We’ve been doing better recently, which is a good sign.”

This has been a year of upheaval for Hong Kong — even remote industrial areas like San Po Kong are not immune: pro-democracy protesters have clashed with government supporters at a nearby Lennon Wall, and recently a citizen from the area interrupted the wedding ceremony of a police couple. Next to San Po Kong is Wong Tai Sin, where there have been major protests since July.

In 1967 San Po Kong was the site of another protest, when workers from a plastic-flower factory rallied for their rights. The police clamped down, firing tear gas and shooting wooden bullets. Some of the workers were injured and some were arrested and charged with gathering illegally or fighting.

The protests in Hong Kong this summer, however, are something larger. After years of suppression by the British government, and now by the Chinese authorities, the people of this former colony have woken up and have formed a strong and consolidated movement. San Po Kong is embracing this change, evolving from an industrial area in decline to a vibrant community of arts and culture.

![]()

- Tags: Albert Wan, Bleak House, Hong Kong, Issue 17, Lok Man Law