Photo: Brant Cumming

My first job in China was for the country’s most important state media outlet. Xinhua started life as the Red China news agency of Mao’s Communist army and became the official state newsagency once the Communists won the civil war in 1949. To this day, it remains in pretty much the same role.

At twenty-five, I was given the job of ‘foreign expert’, which meant I was an expert in speaking my own language. Not a high bar—but it got me a one-year work visa along with some very valuable insights into the strengths and weaknesses of China’s state-run media outlets.

On my first day, a senior editor took me around the office to introduce me to my new colleagues. Most were polite; they’d seen quite a few of these ‘foreign experts’ come and go. One woman in her early twenties shook my hand and said, ‘Nice to meet you’, then asked ‘Why is the Western media so negative towards China?’ It seemed like a bit of an abrupt question, and I fobbed it off. But then two more colleagues came up and asked the same thing.

In 2010, the Olympics—and protests that followed the torch relay—were still very fresh. State media, as well as some netizens, had begun picking apart Western media coverage of the torch relay but also of China more generally. The narrative didn’t come from nowhere—there were plenty of assumptions and mistakes in Western reporting to seize upon. And there was also a perception gap between daily life in China and how the country was portrayed in overseas media reports.

The idea that the Western media were out to ‘smear’ China was a pretty baked-in assumption in China. Many of the world’s media were blocked or heavily restricted. And part of the reason Xinhua hired me is because Beijing had thrown a few billion dollars at its state media giants to try to increase China’s voice in the international arena.

The authoritarian nature of China is familiar to people outside the country. The more outrageous examples are pretty obvious. Blocking and banning views and information sources that the party can’t control. Arresting people for expressing dissenting opinions and sometimes jailing them. Outlawing any form of group organising that the party isn’t in charge of—things like independent labour unions, civil society groups that express dissenting political views and so on.

We’ve seen recent examples at a personal level involving Australians. Cheng Lei, the Australian CGTN presenter, was disappeared, locked in a cell and cut off from lawyers, family and the outside world for six months while they interrogated her to build a state secrets case. She’s still in a detention centre now, and still hasn’t been charged.

Living there, I saw, too, on a daily basis the smaller things that showcased the party’s absolute obsession with controlling others: banning tattoos on television, banning celebrity gossip sites for promoting bad values, banning foreigners and ethnic minorities speaking dialects from live-streaming platforms and, in the case of Hong Kong, limiting free speech and destroying the quasi-democracy that the city still had, because a huge proportion of Hongkongers weren’t complying with Beijing’s wishes.

Aside from the state, I also saw the humour that many people have about all this, the cynicism, the measures they use to get around these things. There are more moderate voices in Chinese state media, who from time to time pick holes in some of the foreign media coverage of China—and rightfully so, at times.

.

There has been a fair bit of reporting out of Canberra in recent years that appears to take the word of Australia’s security agencies, or government sources, or sometimes US sources at face value. Things like secret dossiers about Wuhan, database lists of Communist Party members, supposed spies seeking to defect. It’s not that these stories shouldn’t be pursued, but the motivations of the sources pushing these stories need to be questioned as well. It’s not good enough to prepare it all from the perspective of Australian security agencies and then try to get a last-minute comment from the Chinese embassy.

We rightfully cast a cynical eye on China’s government. Sometimes I feel we need to apply similar cynicism to our government when doing these sorts of stories. Take for example the situation that saw myself and the Australian Financial Review’s Mike Smith get rushed out of China. The only reason we were visited by police and had an exit ban imposed was because it was retaliation for raids the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) carried out on four Chinese state journalists in Sydney. But the Australian public was left in the dark about ASIO’s actions, as were we. So that context cast things in a very different light, and it was at no point revealed by the Australian side. It was revealed by the Chinese side only after we were safely back here.

Clearly, both China and the West have grievances about one another’s media. Diplomats in Beijing used to tell me that it was commonly raised by Chinese counterparts during meetings. The Chinese side didn’t expect that the Australian government could control the media, I was told, but had an expectation that the Australian government would push back publicly about some of the ‘negative’ coverage. And on the Chinese side, that same government would, through its propaganda agencies, continually whack Western governments in its English-language media, particularly the Global Times.

With the expansion of digital spaces, these divisions have become more protracted as Western media struggle to contest the Chinese language space—not just in China, but globally. Through both censorship and protectionism, the Chinese state has funnelled an entire population towards a single messaging platform: WeChat. The others are all banned—Whatsapp, Facebook, Twitter etc. WeChat has also become the primary distribution channel for news—everyone from Chinese state media to small time bloggers uses WeChat public accounts to get their news out. It’s of course the indispensable app for first generation Chinese migrants, and that’s why the major political parties make such use of it when campaigning in elections.

But everything on WeChat is subject to the Communist Party’s censorship, whether by algorithm or human intervention. And therefore many of the most popular sites and accounts for Chinese language news anywhere—not just in China—are on WeChat and are being censored by Beijing. We’re talking local news about Australia for Australian citizens.

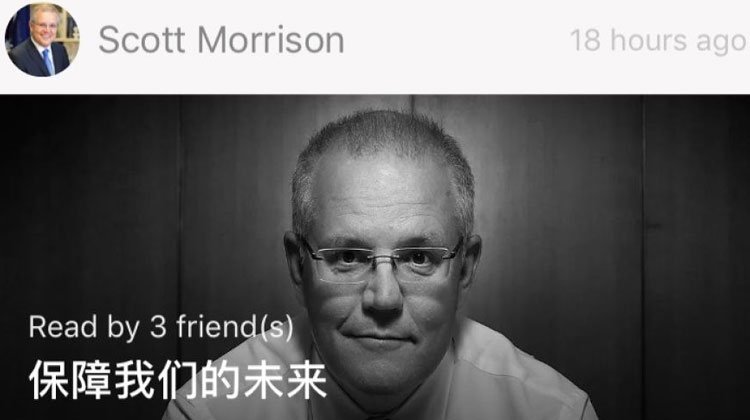

A good example is the recent uproar when a low level official in China’s government posted a provocative picture on Twitter about the Australian SAS war crimes investigation. The news in Chinese on those Australian WeChat accounts was being funnelled through the Chinese government’s censorship guidance. You might remember when Prime Minister Scott Morrison used his own WeChat account to give his response, in Chinese, directly to Chinese Australians, WeChat censored it and deleted it.

It is real problem to have a foreign government creating a digital ecosystem to control the narrative for some Australians in Australia.

China pioneered the decoupling of the internet within its borders and, through WeChat’s censorship, is continuing to promote a restricted information world. As Morrison’s recent failure to use the platform showed, engaging on WeChat is a mug’s game, and hopefully our political parties will become more aware of that in the future.

![]()

This is an edited extract of a China Matters ‘Rethinking China’ lecture given in Sydney on 24 February 2021. You can watch the lecture at this link https://chinamatters.org.au/events-3/lecture-series/feb-2021-bill-birtles/

- Tags: Bill Birtles, China, Free to read, Notebook