Wat Phra Kaew, a new royal pagoda, is under construction near the palace. It promises to be very beautiful. The courtyard in the centre of which the pagoda will stand is ringed by an immense cloister with wooden columns. A large sala will provide sanctuary to numerous pilgrims.

The supreme patriarch of monks is overseeing construction. He is an old man of seventy-five, with nothing in his costume to distinguish him from the other monks. We are introduced to him. He shakes us by the hand most amiably and declares himself delighted to converse in Siamese with Mr Mitchell-Innes, one of our travelling companions. The venerable monk, who speaks a pure form of Siamese, lived for many years in Bangkok, where he studied Pali, a tongue in which he is said to be highly versed.

The supreme patriarch informs us that he has 3,000 Cambodian monks under his jurisdiction. I have someone ask him if he has old sacred books. He responds in the affirmative and makes an appointment for them to be shown to us.

Whenever the venerable monk goes abroad in a coach, everyone squats as he passes along the street. This is a sign of veneration in Cambodia.

The native courthouse is nearby. A hearing is coming to an end. Both parties in a civil case are still sitting on their mats, and the three native judges are at their table. The president of the court shakes us by the hand and leads us on a visit of the remand jail. It is a kind of police station, with camp beds. There are four or five prisoners in each section. Although only on remand, they are in irons on one foot. The fairly light chain is left free during the day. But at night, one end is attached to a ring set into the ground or the wall.

There is a school, where numerous children learn our tongue under the direction of French teachers and native assistant teachers.

On a vast plot stands the pagoda reserved for cremations. Flames rise. We will be able to attend a funeral ceremony. A mound was built of solid masonry, five or six metres square. At each angle, immense wooden columns support four overhanging roofs twenty metres high. In the centre, the corpse of an old woman is in the final stages of burning. The shape of the body can still be clearly discerned. All that is left is twisted bones. A sinister-looking old man approaches with a pitchfork, kindles the fire and pushes fragments closer together to hasten combustion. Near him, a family representative wears a broad white scarf. White is the colour of mourning among the people of the Far East.

A pot of reddish clay placed next to the pyre attracts our attention. It contains rice, cooked and then distributed among the ravens in equal parts in each of the pagoda’s four corners.

Some fifty metres beyond the pyre, under a sala of bamboo, the deceased woman’s family squats in silence, their faces turned towards the pagoda. The woman’s two daughters are dressed entirely in white, their heads shaved. Before them are rattan baskets containing bananas, mangoes and oranges they will present to the monks once the funeral ceremony is over. Grandparents, parents and husbands are mourned for three years. A widow may not remarry before the three years have elapsed. During that period, those in mourning shave their heads every two weeks. They may not wear any jewellery or ornaments, and they are required to continue wearing white clothing.

We leave this gloomy compound with heavy hearts. All around us, ravens caw through the air and, in the swamps, giant toads emit their sonorous bellows.

We wake to the clang of metal. In the street, men are doing corvée. They are bound at the ankles by iron shackles linked by a fairly loose chain that will not hamper their movements excessively. A rope tied around their waist allows them to lift the chain in the middle and thus walk without too much difficulty. These are Cambodian convicts. There is only one kind of punishment: jail, for terms of varying lengths.

It is six o’clock in the morning. Near the hotel, on a vast square, the market is in full swing, spread out under stylish metal hangars. It is always a curious sight.

An enormous crowd makes a fiendish din. Vegetables and fruit of every kind are available, notably areca and bamboo shoot salad, beautiful eggplant, fresh lotus and even banana flowers that will be dressed as a salad; one odd-looking vegetable is shaped like the nozzle of a watering can, with in each hole a blackish seed that barely rises above the round surface. I am told these are lotus seeds, to which Cambodians are especially partial.

Here is a splendid spread of offal, which a boy fans continuously to keep the flies at bay. The offerings are displayed in large bowls; everything is very clean and as carefully ordered as on the best offal stands in our own Halles Centrales. Barbers work side by side with money changers, who count ligatures of sapeques*, and mobile food vendors around whom squatting coolies enjoy jellies and spicy stews. A woman is preparing golden dumplings and appetising flat cakes. Another adroitly rolls cigarettes made of fine local tobacco, more golden in colour than that of Bangkok.

Large blackish fish, looking somewhat like our red mullets, frolic in deep basins as if trying to escape their confinement with prodigious leaps. Once a buyer has made their choice, the fishmonger stuns the poor creature with a violent blow of a stick; from then on, it will wriggle only in the skillet.

Here are large sacks containing rice, pure white and of high quality. The weighing method is most curious. A rudimentary Roman scale consists of a bamboo stick marked with notches. The merchandise is suspended to a hook at one end while a weight slides along the notches, looking for the point of equilibrium around a mobile axis.

We saunter through the arcaded shops next to the market. For the monks, it is the collection hour. They go alone or in groups, bare-footed and bare-headed, clad in their yellow habits, holding on their hip their bowl, or baht, of which only the metal lid is visible. The body of the receptacle is covered with cloth wrapping that hangs down below the bowl itself.

The monk positions himself under an arch and waits, speechless and motionless. If no one comes to him, he withdraws. But most of the time, one of the shop’s occupants advances towards him, holding an earthenware pot. With a large spoon, he places a large quantity of rice in the baht while the supplicant mutters a prayer in a low voice between clenched lips. If it is a woman who dispenses alms in this manner, the monk turns his head away. Poor darling: he knows that the flesh is weak!

I follow two young novices, two nen aged fifteen and sixteen, highly nimble and very engaging of person. Within a few minutes their bowls are full. When they give up their robes, which they can do at will, they will find a companion without any difficulty among the friendly young women who rushed to serve them.

I hear shouts. It is a Chinese woman, somewhat brutally castigating a little cherub a few months old. The father hears, too: he grabs the child, and, with one vigorous blow of the fist, sends the heartless mother to the ground.

Next to her is another Chinese woman, who, with much shouting and a rattan cane in her hand, remonstrates harshly with a bambino aged five or six, who whines most convincingly with his fists in his eyes. The cane strikes the ground, and the boy prostrates himself before the author of his days. For several minutes, he waits for permission to rise, and at last escapes, delighted to be let off so lightly. His eyes are dry, and he smiles. Children! They are the same everywhere!

In the sky, enormous flocks of herons advance in triangular formation, then suddenly change into infantrymen and rearrange themselves in single file. Battalion succeeds battalion. There are thousands of them.

Here is a handsome building in the European style with on its frontispiece the wording Trésor du Cambodge. Next to that is a superb bridge with a most unusual railing. It consists of the scaly body of a snake or dragon made of stone, the naga dear to the Khmer, who consider it a god. On either side of the bridge, the naga spreads its seven heads like a fan.

Let us walk across the bridge to a verdant, well-maintained hillock. We follow a gently sloping path. Here are monasteries; cages with tigers, snakes, monkeys and otters; a wide stone staircase guarded by naga, lions with horrible maws, warriors armed with clubs. All of this is of recent construction, just like the pagoda that rises at the top of the hillock. On one of the terraces, a superb bas-relief in cement represents a battle. It is a copy of one of the most beautiful motifs in Angkor Wat.

The pagoda is open. It contains bas reliefs in red and golden cement, as well as more representations of Angkor. On the shutters are odd-looking paintings showing kings, genies and bayadères. The design is most attractive. Here is an insignificant Buddha, no clocks, but paper parasols.

Behind the pagoda is the great phnom. We stand in front of the construction that gave its name to the city.

Phnom Penh has two etymologies. Some claim that it means “full mountain”, while others argue instead, and with greater likelihood, that it recalls a wealthy widow named Penh who had this phnom, or artificial mount, erected and surmounted by a pyramid to atone for the sins committed by her husband. In his admirably exhaustive work on Cambodia, Mr Moura reports being shown a tenth-century text in which it is mentioned that this phnom was erected in the year of Pra Put Sacrach 1529 (985 or 986 AD).

The phnom consists of an immense ribbed bell resting on a square base and built of masonry, covered with plaster and whitewashed. On each corner, monsters and warriors are at prayer. The spire seems to rise about twenty metres above the base. The entire mount dominates the city by about sixty metres. A pretty vista can be enjoyed from this spot even though the horizon is partly blocked by vegetation.

Dotted around the pagoda, smaller phnom contain the ashes of wealthy Cambodians.

The pagoda, which was consumed by fire on several occasions, has just been restored and most skilfully rebuilt, following its original design, thanks to the good offices of a Frenchman, Mr Fabre.

Let us not forget that we are not on French soil but in a protectorate. Norodom reigns, surrounded by a council of ministers presided over by the resident superior. The monarch receives annual emoluments of 300,000 piastres, to which should be added various dues for customs and monopolies. The king collects perhaps 500,000 or 600,000 piastres in total poor devil!

Cambodia is the land of venality par excellence. For native functionaries, appointments are — and especially were — merely a chance to drain the workers’ small fortunes. The king retains the right to grant appointments, so no trick is left unused to conciliate the monarch.

The palace buildings, which we can enter and visit, seem singularly dilapidated and in pitiful condition. We are shown the entrance to the harem. Every night at about eleven o’clock or midnight, His Majesty takes his leave of the harem’s women and crosses the courtyard to return to his private apartments. Music plays on this occasion.

Ah, the harem! What power it wields and, especially, what influence it once had on the kingdom’s destinies!

Our own kings’ courtiers used to attend the monarch’s morning levee. It is here, in the relative familiarity of conversation, that every rumour from the town or the court found an echo, intrigues were hatched, and favours dispensed.

In Phnom Penh, it is the king himself who is off to attend to the ladies coucher. As you can imagine, conversation must play a major part in the late hours the old monarch spends each day among these yellow-skinned sirens. It is also here that intrigues play out, that such or such favourites, wilier and more enticing tonight, fired up by particular amounts of dollars familiar to them, lay siege to the king to obtain the appointment of a functionary to the post he solicits. It is here also that the beautiful Siamese ladies introduced on purpose miss no opportunity to maintain in the king’s heart feelings of affection towards the land they left behind but continue to serve.

These charmers of Phnom Penh number 400 or 500. This little world swarms and is difficult to rule, the ladies being money-grasping and, it must be said, far removed from royal favours. Scandalous court gossip is the only topic of conversation.

The story is recounted of the fortitude with which old Norodom received injections of Brown-Séquard’s fluid, which the Navy physician Dr Pinard, later succeeded by Dr Pineau, came to administer each day. Apparently, the result was astonishing. Like Goethe’s Faust, a chirpy Norodom could sing to the God of Spring: “Bring on the pleasures, the young mistresses!” The ladies spoke of nothing less than of raising a bronze statue by subscription to the worthy, learned regenerator, their lord and master. Alas, thrice alas! The effect of the precious fluid was short-lived, and a reaction ensued, violent to the point of endangering our royal breeder’s life. It became necessary to give up the syringe! Our beauties were inconsolable!

But perhaps not. Listen to these adventures, scrupulously related, that took place under the hot sun of 1898.

His Majesty Norodom had at his court two Chinese boys, most engaging of person, with languorous, almond-shaped eyes and whom the requirements of service occasionally brought into contact with the ladies of the court — at a respectable distance, naturally.

For the shepherd, introducing the wolf into the sheep pen is the supreme folly, all the more so when the ewes are not repelled by the wolf and when the wolf itself, not ferocious in the least, appears in the form of a suitor full of promise. Troubling glances were exchanged with two of the royal favourites. Our boys knew the protocol. Thanks to the complicity of a servant girl, they had billets-doux conveyed to the objects of their passion requesting to be allowed to love. This is absolutely authentic! How could the ladies refuse in the face of so many respectful submissions? The boys were permitted to love, so love they did.

One evening, trembling and burning with desire, the two adored ones managed to slip among the ladies in waiting as they left the harem. Soon, the Sons of Heaven pressed them between their yellow arms. Oh, Norodom! Yellow, do you hear me? Poor you! You slept, you wretch, even as the stars were at their most brilliant and the mocking moon stretched its luminous crescent over your royal bed. It seems the guards who watch over the Phnom Penh palace do not protect kings.

Unluckily, on their return, the two couples were spotted just as the boys were giving their partners a boost; satiated with love, they were returning to their quarters by jumping over the wall like little porpoises after a nocturnal escapade. Scandal! Sacrilege! Infamy! Dark dungeons! Damp straw! Legs in iron while awaiting death.

Outraged, His Majesty was already searching through sacred volumes for which of fifty-four types of death he would choose for his unworthy servants, when it was pointed out to him that Chinese citizens did not come under his jurisdiction and could be tried only by the courts of the French Protectorate. He had no choice but to submit. No official grievance seems to have been lodged. His Majesty was forced to drain the bitter cup.

This is how an awe-inspiring Cambodian monarch was punished for taking Chinamen into his service.

Yet, Norodom’s cup of woe was not yet drained to the dregs.

This time, it is on the steps of the throne that we find the hero of the adventure. It seems that one of the king’s favourites was beginning to show a degree of roundness that could not be easily explained. The days of Brown-Séquard were long past. A meditative Norodom probed his heart and his loins. No, he was not the culprit. After a long and rigorous investigation, during which frightful threats turned the poor girl’s hot blood to ice, the king learned that the child’s father was his own son, one of his most cherished offspring and incomparably skilled at training fighting cocks. Whom can one trust, dear Lord, if today’s children no longer respect papa’s wife? Laden with chains, the prince now awaits his fate in one of the palace’s chambers.

The monarch is most perplexed, for, if we are to believe tradition, he was once guilty of a similar transgression and still bears the marks of the rattan strokes his royal father arranged to be most generously administered for the occasion. Like father, like son.

Tonight is a time of festivities at the palace. A French illusionist, Master Léopold of Paris, is charged with entertaining the court. The Resident Superior is gracious enough to invite me to accompany him. I would not miss such a chance for the world.

In the meantime, we visit the white elephant, one of the kingdom’s principal characters Captured last year, the young animal has not yet made its formal entrance to the pleasant capital. It is on the occasion of the Queen Mother’s cremation that he will be received with all the regard due to his rank. Unperturbed, he awaits the happy day in a straw hut a few kilometres from the city. This is where we are admitted to the honour of admiring the animal.

Tempted by the sight of appetising bananas, the sacred animal drops all disdain. He kneels and offers wais with his trunk. This elephant is a darling. It is a little lighter of skin than the Bangkok elephants. Long, somewhat thin reddish hairs grow on its forehead and along its spine. Its eyes are whitish, and I count eighteen toenails.

Young and cheerful of temperament, the little elephant never stops provoking his mahouts. He would love to run, gambol and fool around. Alas, his exalted status ties him to the stables. A dozen monks in yellow robes are encamped nearby. Silent and respectful, they contemplate the animal.

The time has come to head for the palace. Lantern carriers attend to the Resident Superior and his guests in the formal courtyard now invaded by an enormous crowd. Conversations in every direction make a formidable racket. There must be thousands and thousands of spectators.

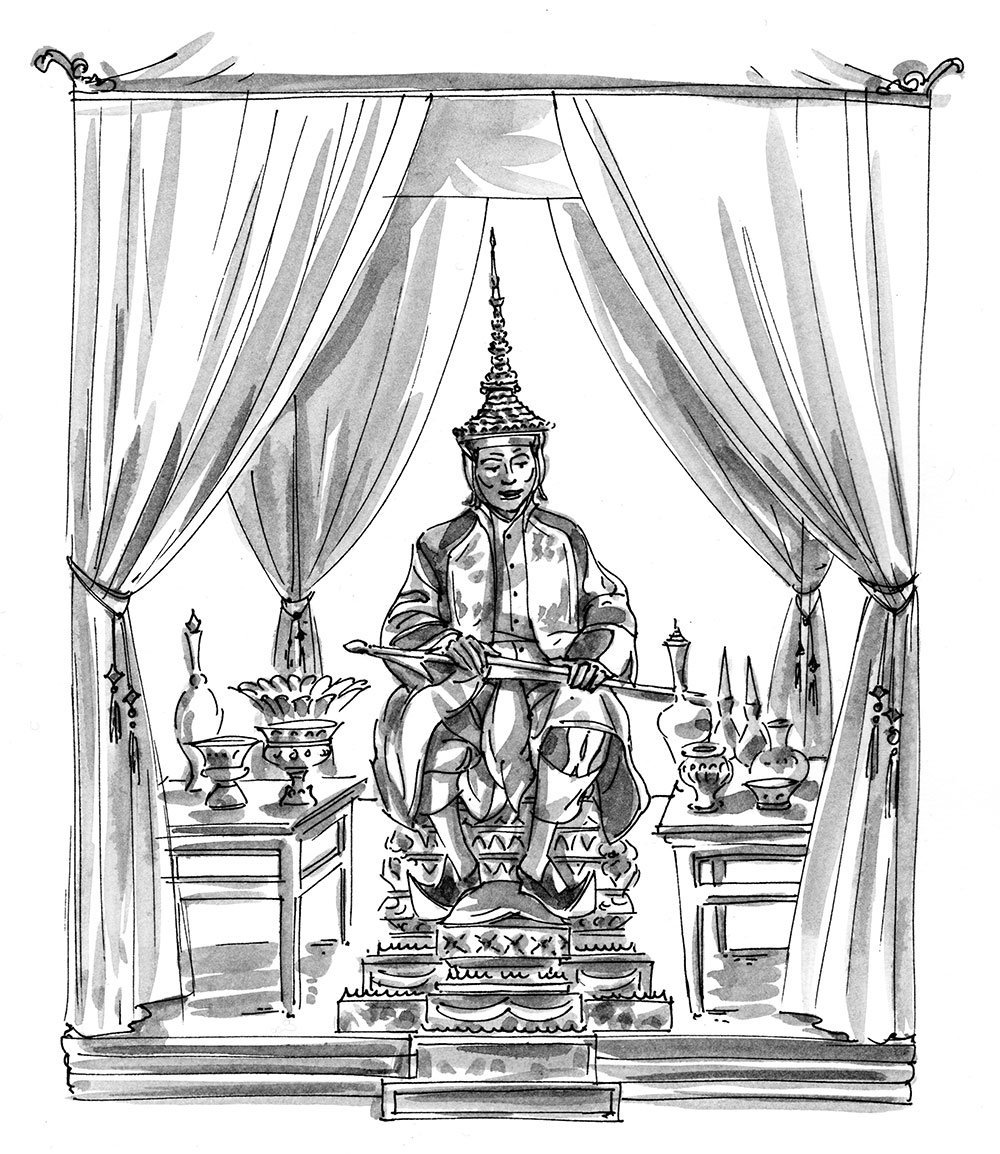

A small stage stands at the back of an immense hangar, sky blue with white clouds on the vaulted roof. Here comes Norodom, a short, emaciated old man, a smile on his wrinkled, astute face. A trace of a moustache shades his lip, but the rest of his face is clean-shaven. Stooping slightly, the king is all amiability and true graciousness towards France’s representative. He wears a white coat buttoned from top to bottom, flared breeches of black silk that end at the knees, black stockings encasing thin calves, and varnished shoes. On his head is a velvet cap with a golden tassel and adorned with a superb diamond crescent. On his coat, he wears a heavy, odd-looking chain of solid gold. On his fingers are enormous rings and, in his hand, a wooden cane of a type I have never seen before, its knob a large ruby set in a gold frame. Also made of gold (and enamel) are the binoculars the king offers us, as are the betel case, the spittoon, and all the utensils spread out on the table facing the royal armchair, in gilded wood and bearing the crown with a cipher on it (it is said that the letter N seen on the furniture and tableware is that of Napoleon III).

His Majesty most graciously offers excellent cigars and ice-cold beer.

On the left, between Norodom and the theatre, squat the royal pages, attentive to their master’s slightest wishes. One of them holds the royal sword, a superb piece of goldwork, as far as I can judge from this distance.

But the most exceptional spectacle is that unfolding to our right. The full troop is gathered: in high spirits at finding themselves almost free, the ladies cackle and jabber, making enough racket to make all the concierges in the Marais district of Paris jealous. There are hundreds of them, mostly very pretty, with smouldering eyes and superb shoulders barely veiled by a silk krama. This entire world looks at us, laughing and exchanging mocking comments. Unfortunately, we are seated a little too far away. Numerous diamonds sparkle in the ladies’ ears.

The illusionist wishes to begin his patter. He requests silence. Nothing doing. In vain, the king himself turns to his handsome lady friends. In vain also, old mamas armed with long rattan canes tap the most determined among them on the shoulder. The attempt to silence these ladies is abandoned. Léopold decides to put up with it. He addresses the king alone. An interpreter translates his every word.

Card tricks, sleights of hand — the king is having fun.

At the sight of the Davenport brothers’ “Spirit Cabinet” trick, the king cannot contain himself. He steps forward and ascends the stage to verify for himself the knots that tie the illusionist’s hands and feet. Behind the monarch stands his latest offspring, a small prince of eight or nine years old, a favourite son who follows him everywhere.

But where the king’s enthusiasm and that of the crowd are given free rein is during the cinematographic performance. They applaud, they scream: it is sheer bedlam!

The old rascal is licking his chops and leaping in his armchair at some of the more risqué tableaux — especially Le bain de la Parisienne, which seems to titillate him to the highest degree. The ladies had better watch out!

*A coin issued by France from the late 19th century for use in Indochina

![]()