Credit: Provided to Mekong Review

Counter-Cartographies: Reading Singapore Otherwise

Joanne Leow

Liverpool University Press: 2024

.

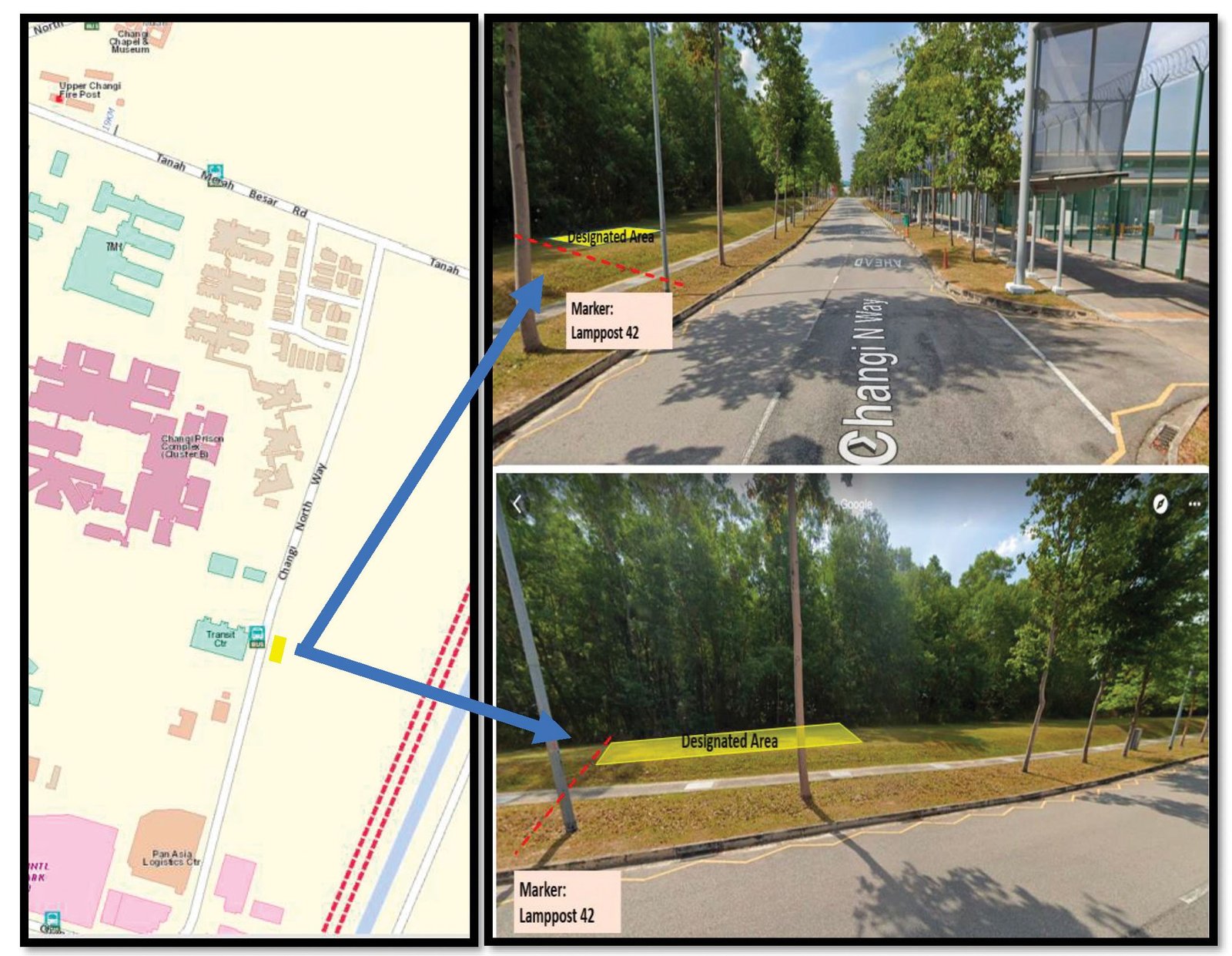

In 2022, when Singapore resumed executions after a two-year hiatus, Rocky Howe, an abolitionist activist, applied for a permit to stage a protest outside Changi Prison. The police rejected him at first, which wasn’t surprising, but his subsequent appeal succeeded , which was. Then he saw the conditions they’d stipulated: the protest location had been shifted to a road behind the prison complex, on a patch of grass next to a specific lamppost—a map was attached to the police’s letter, a bright yellow rectangular box marking out the designated area. Only four participants would be permitted, but the organiser was still expected to “deploy a cordon to demarcate the designated area for the assembly” and hire a licensed security officer to maintain order. Participants would be allowed to hold handheld lights and a portrait of the death row prisoner Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam (even though, by the time these instructions were conveyed, Nagaenthran had already been executed). There had to be a sign at the edge of the designated area saying “Only Pre-approved Participants Allowed”—specifications were provided for the size of the paper (A4), the font (Arial) and the size of the text (size 48). This “assembly” could only be held on the specified date at the specified time of “2349hrs to 2359hrs”—a grand total of ten minutes. “Pre-event publicity” would not be allowed, nor could journalists be invited to cover this ten-minute four-person demonstration. Any deviation from these conditions would turn the protest into an illegal assembly.

Most Singaporeans will never apply for protest permits in their lifetime, but this permit Howe obtained (and ended up not using, given the conditions) illustrates how much power the state has over physical space in the country. Under the Public Order Act, all protests—even solo ones—require police permits, to which conditions can be attached. The authorities are able to dictate where Singaporeans can be, when and for how long. They are empowered to regulate how citizens express themselves in physical space.

To be Singaporean is to know that public space is really more like state space, and you can’t hold on to things. Buildings and parks appear and disappear, constructed and demolished by the industrious and back-breaking efforts of a massive low-wage migrant labour force. Beloved landmarks can vanish, their social significance subordinated to the priorities of urban planners. If there isn’t enough space, land can be (politically) willed out of the sea as “reclaimed” land—key features of Singapore’s much-admired city skyline stand on ground that previously did not exist.

It’s this power that fascinates the Singaporean academic, writer and poet Joanne Leow in her monograph, Counter-Cartographies: Reading Singapore Otherwise. She points out the enormous amount of control the state has over physical space in the city-state, from the power given to the government by the Land Acquisition Act to spectacular missions to dominate nature, as seen in the climate-controlled domes of Gardens by the Bay. Every bit of Singapore and its islands are mapped and zoned, factored into a Master Plan that the government reviews every five years. “This involved paradoxical issues of scale: even as the government took control of ever larger swathes of land, it micro-managed them in ever smaller plots and zones,” she writes, arguing that this makes political power legible, reminding citizens over and over how little input they are allowed in the face of state agendas. Singapore is internationally celebrated as a well-designed, efficient city, attributed to the skill of far-sighted political leadership, but it’s important to remember that this supposed far-sightedness is, in large part, made possible by how long the People’s Action Party (PAP) has been in power—sixty-five years and counting—and the amount of power it wields.

“Lee’s vision of a tropical garden city was an authoritarian fantasy of a ‘clean and green Singapore’, in effect marrying the lushness of an ideal tropics with the purity and orderliness of a regimented and regulated society,” Leow writes with reference to Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first prime minister and “gardener in chief”. “A corollary to urban planning and zoning, the tropicalization of Singapore’s built environment was directly linked to Lee’s mission to cultivate the populace itself.”

Photo by Wren on Unsplash

It’d be depressing if all Leow did was point out the overwhelming extent of Singaporean state power, but the second half of the monograph’s title is “reading Singapore otherwise”. One might not be able to evade the state entirely, but people don’t live at the bird’s eye view level of the maps that civil servants pore over and fiddle with. Lives unfold on the ground, surrounded by the messy minutiae of the everyday, in nooks and crannies that cannot realistically be policed by external forces. The work that Leow conducts close readings of—spanning the mediums of film, multimedia, poetry, fiction, theatre and graphic novel—are examples of (mostly) Singaporeans who, if not directly confronting the establishment, at least refuse to conform to top-down formulations of how to live on this island.

These are attempts, Leow argues, to “excavate, circumvent, wayfind and confabulate” outside of the state’s politically motivated narratives and boundaries. Some of the works she analyses—like Tan Pin Pin’s documentary, To Singapore With Love, effectively banned in Singapore, Sonny Liew’s epic Eisner-winning graphic novel, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, or Alfian Sa’at and Marcia Vanderstraaten’s play, Hotel—I was already familiar with before reading this monograph. Others, like the multidisciplinary artist Charles Lim Yi Yong’s SEA STATE series, ila’s transmedial work, ‘A Fluid Borderless Past’, or Tan Shzr Ee’s semi-autobiographical book, Lost Roads: Singapore, I discovered through Leow’s eyes. These pieces variously unearth parts of Singapore those in power prefer to bury (excavate), evade official regulations to create their own meaning (circumvent), explore alternate routes away from state-sanctioned paths (wayfind) or imagine different possibilities for Singapore’s past and present (confabulate). These artists refuse to accept state narratives—always so prevalent in Singapore—wholesale; instead, they’re determined to direct our attention to what lies beneath a veneer of managed success. Take Leow’s reading of Lost World, a short film by Kalyanee Mam, a Cambodian filmmaker and the only non-Singaporean whose work is analysed in this monograph. In it, Vy Phalla, a villager from Cambodia’s Koh Kong province, travels to Singapore to see the results of the sand-dredging that has destroyed the natural environment of her home. Leow writes: “Taking the sand and plants in her hands, [Phalla] sees what others cannot as they admire the technological feats of the Gardens [by the Bay] and Singapore’s ecocidal infrastructural project of reclaimed land: that they are ruins and ruination that extend beyond its own borders and continue to affect ecosystems and communities that had been rendered invisible.”

Counter-Cartographies doesn’t make for easy, casual reading; it’s an academic text written in the language and conventions of that field, obviously different from the poetry, fiction and non-fiction Leow writes elsewhere. (I still think of her creative nonfiction piece, ‘Journalism and Jiujitsu: The Gentle Arts of a Dictatorship’, written for Catapult in 2016 about her experience as a journalist and news presenter in Singapore, from time to time.) But the ideas at its core are inherently relatable—for all the efforts of powerful institutions, people will find ways to live their lives despite, and perhaps also in spite of, predetermined margins. Whether academic, artist, filmmaker, poet, writer, journalist or activist, there will always be Singaporeans who find ways to express difference in a city that seeks to manipulate, manicure and micro-manage. It is as Leow says about Alfian Sa’at’s book of flash fiction, Malay Sketches: “The panoply of fictional spaces in this collection, as produced through the social lives of minority Malay characters, resists the planned and zoned maps of the country, producing a way through this city without maps but with memories, bodily sensation, and an awareness of the structures of power that govern their living space.”

Successive PAP governments have succeeded in imposing order (read: control) over the country in many ways, from public housing policies that prioritise heterosexual, married citizen couplings to mapping out spaces and willing them into being over decades and generations. But as the films, stories and art Leow studies show, no amount of official cartography can obliterate human agency, curiosity, memory, love and yearning. In “reading Singapore otherwise”, Leow has drawn our attention to people who are living, being, otherwise.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Issue 36, Joanne Leow, Kirsten Han, Singapore