I almost don’t notice Laxman at first.

It’s the end of a twelve kilometre walk on Bangalore’s roads; roads that loathe pedestrians with a passion. My ears are ringing from the relentless peak hour honking on Hosur Road and I fear that the shafts of yellow light shooting out from the cars and scooters crawling past me may damage my sight permanently.

Despite the cool weather—it was supposed to rain heavily through the day but didn’t—a fine film of sweat sticks to me, like cling wrap speckled with dust and grime. They’ve hitched a ride as I wended my way north towards HSR Layout, a suburb of southeast Bangalore. All I can think of is a cold beer and a shower.

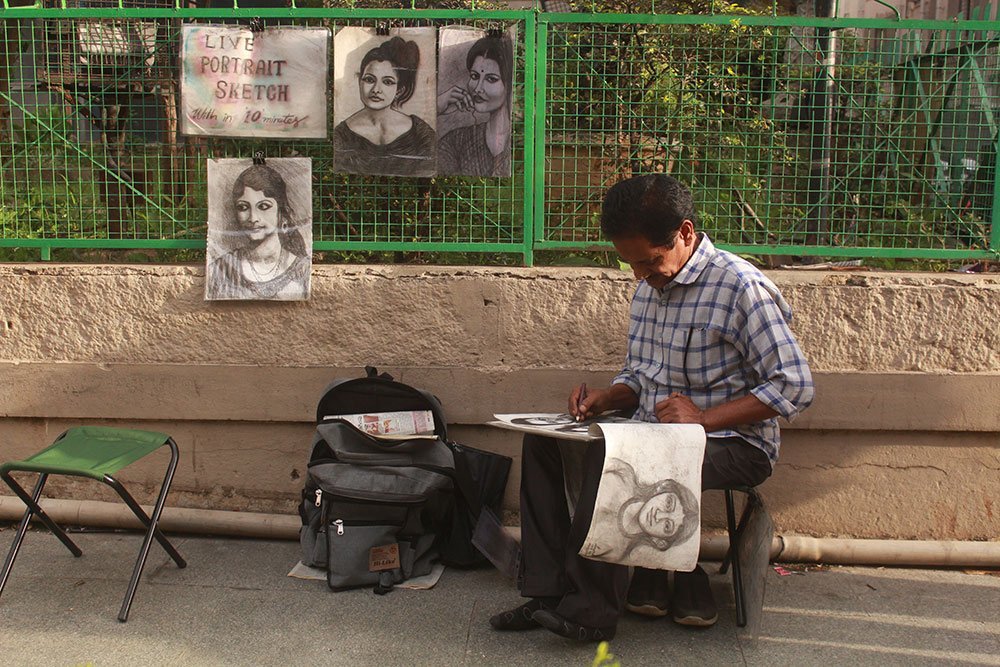

Even otherwise, he would be easy to miss. A tiny man made tinier because he’s hunching over his phone, Laxman occupies one of the few non-descript parts of Church Street—on the pavement somewhere between Amoeba HM Leisure and Little Goa. I’m past him before I notice the rat-a-tat-tat of the sketches fluttering against the railing to which they are taped.

Laxman doesn’t notice me either.

With his left hand he holds up the phone, eyes screwed to the screen. His right is doubling up—its fingers sketching the face he sees on the screen, the side of its palm keeping the precariously perched writing board with its stack of drawing sheets in position on his thigh.

‘Banaoge? Will you make?’

Hindi and English both come tumbling out together. I feel nervous, for no other reason than the fact I’m so used to looking past, through and away from life on the Indian pavement that engaging with it now seems like an act of daredevilry. Laxman looks up uncomprehendingly from behind his mask. I’ve broken his reverie and he’s trying to make up his mind about how he feels about it.

In time, though—two seconds, maybe three—his eyes motion towards the miniature chair—stool would be more apt—placed two feet away from him, and identical to the one he occupies. I’m unsure. It’s one of those foldable types with a small piece of cloth stretched across that doesn’t look like it could bear much. Laxman, however, jabs towards it again so I descend, gingerly at first, and then, as the cloth holds up under the strain, I settle more comfortably. Relief flows through me like water through a parched throat.

Laxman meanwhile is giving me the once-over, peering out intently from behind thick spectacles.

‘How long have you been doing this?’

‘Ten minutes, sir, less than ten minutes’

‘No, no. How long? How long? Kitne time se?’ Again that pell-mell admixture.

‘Twenty years,’ he smiles.

‘In Church Street?’

‘No, no; many places, many places. Stay still.’

I take that as an order to stay quiet, too.

Having absorbed all he can from staring at my face, Laxman gets to work. The writing pad is at an angle facing away from me, so I can’t see what he’s doing. All I can see is the flurried movement of the hand with only an occasional pause when the artist looks up to unearth some more information from my face. I look back, trying not to blink.

It is surprisingly difficult to stay still for more than a few minutes. Intrigued though I am by the process, and even though it’s been less than five minutes since I sat down, part of me feels impatient for it to be over. I pass the time by observing the reactions of passers-by. Non-descript or not, this is still posh Church Street in yuppie Bangalore and foot traffic is heavy. Nearly everyone coming from behind me glances back as they walk past—first at what Laxman is doing and then at me. It is mildly annoying that they know more about the sketch than I do.

‘Painting ho rahi hai (is being done),’ one gentleman announces to his companions.

‘Arre good yaar,’ is another’s verdict.

A boy, who can’t be more than ten, is fascinated. He stands right next to Laxman inspecting the work with a critical eye.

‘Kaisa hai (how is it)?’ I ask him.

‘Accha hai (good),’ with a vigorous nod of his head.

‘Tum bhi banwa lo (why don’t you get one made too)?’

‘Nahi, abhi jaana hai (no, I have to go).’ He disappears with a quick smile, following the sound of his mother’s voice in the distance.

Without meaning to, we have become an exhibit, Laxman and I—the roadside portrait artist and his sweaty subject.

A kurta-clad man on a video call saunters past. He swivels around surprisingly fast for someone of his tonnage and points the camera in our direction. We are being broadcast nationally now—or maybe internationally, who knows—to an unsuspecting audience of one. Laxman is busily at work but I’m unsure how to react so I give a watery smile before trying on an expression of studied seriousness. Having inflicted us on his phone companion, the citizen journalist shows me the thumbs up and walks off into the gloam. The world gathers itself up and it’s just Laxman and me once more.

He seems to be working faster, the top of his pencil a black blur against his brown shirt. I’m bursting with curiosity but hold myself back from breaking his concentration. Faster and faster the pencil flies, giving what I think are the last flourishes. Finally, it scribbles something on the bottom right of the page before Laxman hands the paper over.

‘Lucky arts.’

It’s a remarkable likeness. A tad on the flattering side—my eyes are more thoughtful and my hair more dashing—but who am I to complain?

‘Ye to bohot badhiya hai (this is very good). How much?’ I still haven’t figured out whether Laxman knows English or Hindi, or both, or neither.

‘Thank you. 200.’

Weekdays are fairly quiet for him. Only three or four people sit down daily though everybody’s glance lingers on his sketches as they walk past.

‘Aapne ye kidhar seekha (where did you learn to draw)?’

‘Five-year course kiya main. Yahan jo Chitrakala college hain udhar (I did a five-year course at the Chitrkala College here).’

‘Aap mujhe sikhaoge (will you teach me)?’

‘Nahi, sir, hum nahi sikha paayega. Aapko Chitrakala jaana hoga (sorry, sir, I won’t be able to do it. You will have to go to Chitrakala). Thank you.’

Eager to get back to the sketch he was working on before my interruption, Laxman is dropping hints. My curiosity, though, tramples over whatever embarrassment I feel. I look down at his drawing materials—pencils with gnarled leads, a black blob of an eraser and other assorted things into a tattered box.

‘Ye saare pencils same hain (are all these pencils the same)?’

When you have so many questions, why does the dumbest always come out first?

‘No.’ He points towards a blue one. ‘This is a Staedtler. Ok, sir, thank you.’

‘Thank you, Laxman.’

I sling my bag over my shoulder, pick up my water bottle, say bye and walk further down the street before calling an Uber. Pick up location: Amoeba HM Leisure.

A last look and there he is. Laxman of lucky arts, hunched on a tiny stool, his eyes pinpoints as they focus on the phone screen, hand scribbling, scribbling away in that tiny nook on Church Street away from the bright lights; on that part of the pavement where few stop but all look back.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Notebook