Halfway through the production of Daniel Hui’s latest film, Small Hours of the Night, the cast and crew noticed cuts in odd places on their bodies. It was the latest intrigue after finding themselves unusually exhausted despite short six-hour shoots. Their dreams, too, had been disturbingly vivid. Then Vicki Yang, the film’s actress, heard footsteps coming from the forest by the set. She insisted on the presence of an additional door in the toilet that led somewhere. There was none.

Hui promptly consulted a medium during a break in filming. He told them about his film, wondering if these inexplicable events had something to do with their choice of location: they were shooting at Gillman Barracks, a former British military camp. “It’s not the place,” the medium replied. “It’s your film. You invoked them by using their actual words. Even if it’s not the actual spirits, the rest of the spirit world is very curious about what you’re doing. They want to be heard too, you know.” He went back to work with the prescribed tools and rituals for exorcism, in case of possession (none occurred).

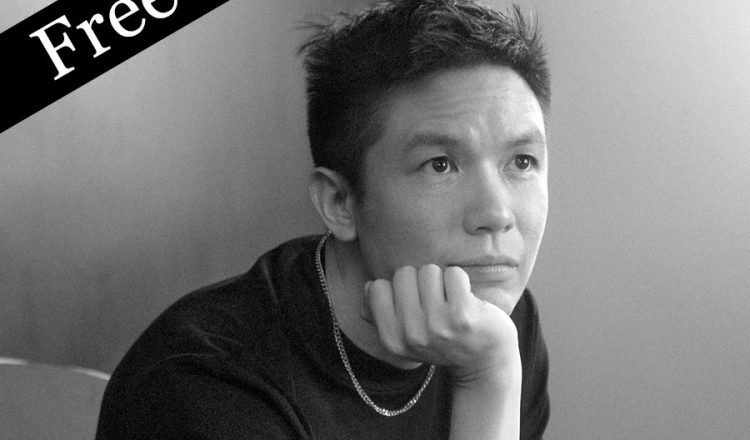

Hui tells me he’s agnostic, but it seemed beside the point. He readily accommodated the presence of the extended, if unexpected, audience of his fourth feature. This might have to do with his familiarity with the intense desire to be seen and heard: for fifteen itinerant years in the United States, he’d rendered himself ghost-like, projecting the sense of alienation he felt from not being recognised as a filmmaker or a person on to America. He’s recently returned to Singapore for the long term. “I wasn’t able to integrate in the US. Now I’ve found a community here that loves, cares and respects me as much as I do them.” He pauses. “I’ve never felt this way in my life.”

He decided to take active ownership of Singapore when he realised its aggressive pursuit of material pragmatism made it easy to ignore everything else. “Beyond the state, this lack of recognition from even our communities leads to a sense of helplessness and anger,” he says. “Our political structure often makes us feel completely powerless. But I’m not interested in criticising the state. I’m more interested in how we take that powerlessness into all areas of life. What’s key here is we don’t want to take responsibility for the power we actually have.” It’s why he loves horror movies, Hui tells me. “They tend to be about a past that nobody knows or thinks about, that returns to create real suffering. It’s history telling us that we cannot ignore it.”

The moral implications of being responsible to one’s community aside, Hui feels he’s being responsible to himself. Left to his own devices in boyhood, he recalled being profoundly comforted by a quote from Arthur Rimbaud: “Je est un autre.” “I is another”—that a self can contain multitudes; the other is as close as the self; the self is as unfamiliar as the other—to him meant he didn’t have to be trapped in one place or “stick to the sadness of being one person”. He could, in fact, possess a “double, even triple consciousness”. He found that in an indiscriminate diet that ranged from Hollywood blockbusters and offerings from Turner Classic Movies to the arthouse cinema that occasionally appeared on national television. Rimbaud’s axiom has shaped all his artistic endeavours: “What’s radical about cinema is that, for the length of the film, the audience completely embodies, sees and hears somebody else—the filmmaker, who has total control over their experience. For a moment, there’s no defined line between self and the other. I am the audience and the audience is me.”

In his films, Hui seeks out peripheral figures, tending to them with the kind of attention usually reserved for prominent historical figures. Shooting on an Arriflex 16SR he acquired on eBay in 2012, he favours 16-millimetre film because of his love of classical Hollywood cinema and because the “Academy ratio really is the best way to frame the human face without leaving too much empty space”. His first feature, Eclipses (2011), situates the preoccupations of a household and the scattered community around them as a site of vital phenomena. As the orbiting camera comes to rest in close-ups of its subjects, flitting through grief, repose and recollection, the audience is invited to regard the monumentality of a face, the way an eclipse in transit commands the complete attention of the observer.

Critical success followed Hui’s next two films, Snakeskin (2014) and Demons (2018). Both films dissect the enigma of charismatic tyrants—a cult leader and a theatre director—via their victims’ testimony. Snakeskin traverses empirical historicism and speculative fiction to create a machine capable of going through time to survey a tapestry of diverse voices before they vanish. In Demons, a vengeful actress stages a campy, pseudo-Baroque comeback in a carpark to hijack the centrality and influence her abuser has on her narrative and deliver him to his denouement. For his latest film, Hui created vignettes drawn from, among other things, accounts of key figures involved in the Toa Payoh ritual murders, in which two children were killed by a self-styled medium and two of his followers, and the Tan Chay Wa tombstone trial, a 1983 court case, now largely forgotten, in which the Singapore authorities took issue with the inscription on the tombstone of a political dissident. Together, they form a loose, fugal trilogy intent on disrupting monologic narratives.

Small Hours of the Night opens with a man and woman—played by Irfan Kasban and Yang in gripping, inhibited performances—who must renounce their familiarity with each other and perform the role of officer of the law and political prisoner. As the man threads and plays a reel-to-reel recorder, a disembodied voice begins to speak of people from the future. He immediately winds the tape forward and the voice screeches, indecipherable. In a series of stylised sequences with searchlights and imposing shadows, the interrogation room transforms into an asylum. The man and woman transform alongside the room, shifting into varied murderers, poets and star-crossed lovers. The woman, now an institutionalised prisoner, is made to recite her expansive knowledge of court rulings. At some point, she finds herself in front of the recorder and a stack of documents. She rifles through them and plays the recording, only to find them devoid of information, the audio recording incomplete. Everything she said had not been for the record; she remains the sole witness to the people and events that have transpired—or possessed her.

There’s a resonance in the blank, redacted records in the film with estranged gaps of Singapore’s history. While the apparatus of power obscures itself in shadows that threaten to shroud and erase the man and woman, the film’s polyphonous arrangement of lost voices is an act of memory recovery, a dense, sonic counterpoint to an unrelenting hold of a collective narrative. In a move to decentralise the composition of history, Hui opted to make “one place and one person invoke all these other places and characters”, effectively rooting even the most liminal of spaces and their inhabitants a sense of seismic, even cosmic, history.

I tell Hui that watching the woman walk through a forest in Small Hours of the Night made me think of how Yang had similarly walked into a forest to travel through time in Snakeskin. “Small Hours of the Night is the inverse of Snakeskin,” he confirms during our meeting at GV x TP at Cineleisure, a collaboration between Golden Village, one of Singapore’s mainstream movie chains, and The Projector, an independent cinema. “The forest is the tunnel of time; there’s wind and it’s super dramatic.” It seemed apt to return where the fugue began: a portion of Snakeskin was shot on that stretch, when it was deserted at 3 a.m., seeming to belong to no one at all. “But there are parties here now and it’s crowded at 3 a.m. ,” he says with a grin.

Hui and his friends host Intervention, described on their Instagram page as an “Irreverenzz QUEER PARTY”. In one of Hui’s many lives, he is a DJ—“DJ enthusiast,” he emphasises—indulging in the joy of partying with friends at cinemas (every edition of Intervention has been staged at The Projector’s venues). In another, he was a film critic who last posted on his blog in 2019. “When I first got into movies, I wanted to be a critic who wrote and thought about cinema. Then I met Yasmin Ahmad, who encouraged me to make films,” Hui says. He credits the Malaysian filmmaker, who he met through a web forum of the Singapore International Film Festival, for the early start in his career. By the time he left for the California Institute of the Arts, Hui had completed three short films, in large part because Yasmin read the script of his first short, The Bracelet (2007), and lent him her video camera to make it.

The soft drone of announcements for shows about to begin punctuate our conversation as evening falls. Hui asks for a smoke break. Standing in an alley with hot, industrial vents blaring above us, yellow boxes painted on the road and trucks passing by, I think about Hui’s next project, Other People’s Dreams, a sapphic love story involving lots of pickpocketing that takes place in these liminal spaces. “I used to hang out in these spaces a lot. Stairwells too. They feel so temperate. We live most of our lives in these places and they belong to us so much more than monumental architecture.” He looks around. “It feels like I can just drift into the rhythm of the notion of these places.” A filmmaker, folding into the symphony of his city.

![]()

- Tags: Daniel Hui’, Issue 36, Sasha Han, Singapore