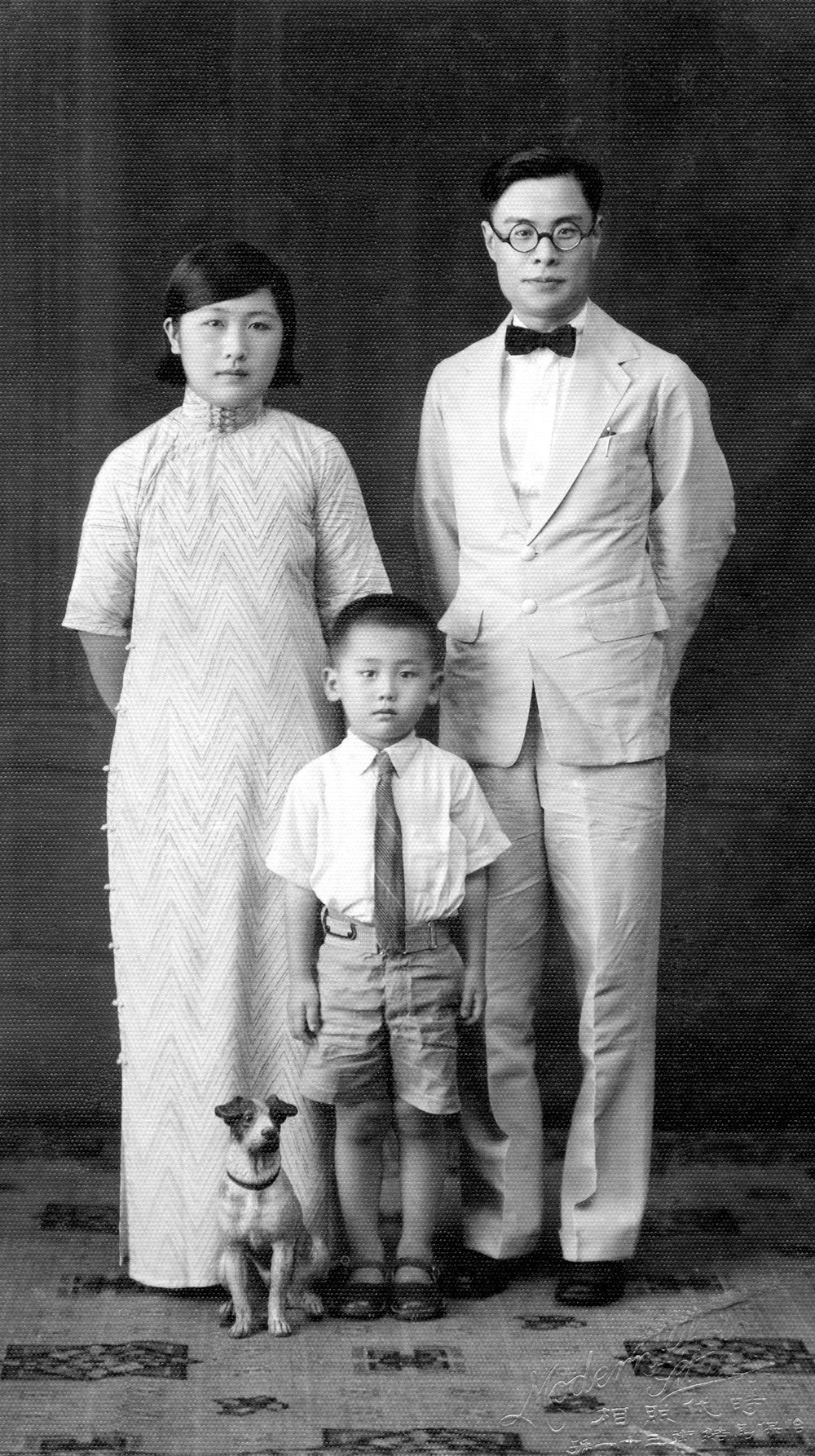

Home is Not Here

Wang Gungwu

NUS Press: 2018

“No matter where you live in the world, we all share one origin. There is a place for all of you here at home.”

In so many words, this is the single message which the People’s Republic of China’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Bureau (Qiaoban) channels to ethnic Chinese across the world. It is a relatively new sentiment. The idea that ethnic Chinese of foreign nationality (huaqiao) are not “blood traitors” but patriots-in-potentia — talent (rencai) to be lured “back home” to contribute to China’s wealth and power — has not long been in gestation. But since the 1980s, it has been written with ever more depth into the People’s Republic of China’s long-term visions. Conceived under the Kuomintang and established by the new PRC in 1949, the Qiaoban languished in the Cultural Revolution and was revived by Deng Xiaoping, who saw in the huaqiao a source of support for reform and opening. Three decades later, Xi Jinping’s “China Dream” counts huaqiao, not just Chinese citizens, among its dreamers; his One Belt, One Road strategy is designed with huaqiao in mind, as business collaborators with critical local knowledge. The recent proliferation of Confucius Institutes signals a new soft power drive through culture and language. “Roots-tracing” tours organised by Chinese local governments bring thousands of children of émigré families to China every year to jog their cultural memories, and awe them with China’s technological and economic achievements. In this era of “new Chinese migration”, all state instruments of persuasion have been mobilised to say that for all Chinese everywhere and everywhen, home is in China.

Generalities die by a thousand particular cuts. History, fortunately, is the domain of the particular. A new memoir by the historian Wang Gungwu has given us one beautiful, incisive cut against any general idea of Chinese belonging.

By all measures, Wang is as ‘Chinese’ as they come, or as Chinese as Beijing might like its Chinese to be. A historian and world authority on both China studies and overseas Chinese historical scholarship, Wang has straddled what are often regarded as two separate fields, and has maintained a lifelong professional, intellectual and emotional commitment to the Chinese world. His voluminous body of history and policy writings concerning China since the completion of his doctoral research in 1957 testify to his rencai, and would fill a small library. He is an inescapable point of reference in any writings about the Chinese overseas. His innumerable scholarly prefaces and forewords alone, in both Chinese and English, are an index by which one can track the explosion of huaqiao scholarship since the 1990s.

- Tags: China, Issue 14, Rachel Leow, Singapore, Wang Gungwu