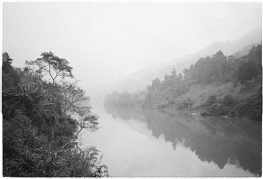

Photo: PhamDuy.com

Who was Pham Duy Khiem? We may begin with that, since most people have never heard the name. The stock answer — the one that might be expected, let’s say, from a young Vietnamese fidgeting in literature class — is that Pham was an author of note who was born in Vietnam in 1908 and died in France in 1974. The real answer is a matter of some debate among scholars (though not many, nor is the debate very lively) and deliberately blanked out by state censors. This fact alone makes the question worth asking.

Pham was an elusive figure historically, so his biographical details are hard to come by. Cursory research tells us that he was born in Hanoi, studied and taught in both France and Vietnam, and perhaps committed suicide in 1974 after writing a few books for which he received awards. Going a little deeper, we learn that Pham was a standout intellectual whose novel Nam et Sylvie helped earn him an honorary doctorate from the prestigious University of Toulouse. Speaking at the presentation, French writer André Lebois called Pham “one of the greatest contemporary French novelists”.

It seems curious that Lebois would describe a Vietnamese author as French, and his words illuminate the source of the debate mentioned above: Was Pham French or Vietnamese? He was both. “People who knew Pham Duy Khiem,” Julia C. Emerson writes in Moussons, “insist that he was both deeply French and deeply Vietnamese and always true to himself no matter what the cost.” And there certainly was a cost.

Coming of age as he did during France’s colonisation of Indochina, Pham embraced, and to a significant degree embodied, two cultures that, in addition to being disparate, were in direct conflict with one another. He received a first-class French education (an exceptionally rare distinction among France’s colonial subjects) and was determined to transcend the contradictions inherent in his situation. Rather than choose between the two cultures that in equal parts defined him — as one was supposed to do in those days — Pham attempted to pull them closer together, or at least facilitate a higher degree of mutual understanding. While living and studying in Paris, for instance, he gave talks on Vietnamese literature and culture, something he continued to do throughout his professional life.

When his studies were completed Pham returned to Vietnam. He taught French, Latin and Greek at an esteemed lycée in Hanoi for a number of years, publishing articles and delivering lectures prolifically. Then, in 1939, he volunteered to fight for the French in the Second World War, despite not holding French citizenship — unheard of among Vietnamese. His brief career as a soldier ended when the Nazis overran the French army and occupied Paris, at which point Pham again returned to Vietnam and undertook a number of literary projects, including a collection of reworked Vietnamese folk tales recently translated into English under the title Legends from Serene Lands, to which I’ll return presently.

After the war, as France launched its bloody campaign to reconquer its former colony, Pham remained stubbornly apolitical, to the chagrin of many of his compatriots. He declined to join the struggle for independence, or even voice support for the Viet Minh, and continued to concentrate on his writing, which is not to say that he endorsed what the French were doing to his country. In quiet motions of protest, he reportedly spoke only Vietnamese and was unwilling to write textbooks for the French government.

In spite of everything, Pham maintained that France and Vietnam could overcome their turbulent history, reconcile their differences and ultimately embrace the common ground he (devoutly, it seems) believed existed between them. Realising this vision became an overriding ambition in his life, to the point where, in 1954, he entered Ngo Dinh Diem’s government, eventually becoming South Vietnam’s first ambassador to France. While this put Pham in a unique position to influence the process of normalising relations between the two countries, it was only a few years before he was disillusioned with politics. In 1957, upon voicing harsh criticism of Ngo Dinh Diem’s administration, he was relieved of his ambassadorship.

He remained in France, where he continued to teach, though now it was for low pay at schools of low or no prestige. Many of his old friends, regarding him as a quisling, cut ties with him and neglected to return his letters. Publishers rejected his work. Fading into academic and literary obscurity, he fell into a consuming depression that would plague him for the rest of his life.

Pham visited his native land once more, in 1968, to view the devastation wrought by the Battle of Hue, for which he reportedly blamed the North. He lived out his days in western France, drowning himself in a pond behind his home in December 1974.

In her Moussons article, Emerson relates an anecdote that in her view illustrates “the philosophy that underlay [Pham’s] approach to Franco-Vietnamese relations”. Appearing on a French radio program in 1938, Pham told listeners a fable about a fisherman who falls in love with the beautiful daughter of a powerful mandarin. Said fable happens to be the opening story in Legends from Serene Lands. Titled “Love’s Crystal”, it tells of a young girl of “great beauty” who, like all young girls of this particular time and place, is not allowed outside her father’s palace. Every so often, as she sits near her window, she glimpses a fisherman’s boat on nearby river. The fisherman sings, and the girl falls in love with his voice, though she has never seen his face. Suddenly the fisherman stops coming around and the girl falls ill, having grown dependent on the sound of his voice. Upon learning the cause of the girl’s condition, her father arranges for the fisherman to pay her a visit. When she sees him her old feelings evaporate; she feels nothing for him or his voice. The fisherman, having fallen madly in love with the girl, collapses and dies from tuong tu, or a broken heart.

In the process of exhuming his remains to move them to their “final resting place”, the fisherman’s family finds a translucent stone inside the coffin. They use it to decorate his old boat. When the girl’s father happens upon the stone, he buys it and has it fashioned into a teacup. “Each time tea was poured into the cup, one saw the image of a fisherman in his boat, slowly sailing around the cup.” The girl hears of this and wishes to see for herself; when she does, she cries into the cup and the cup disappears.

We need not speculate about Pham’s interpretation of this tale — he provides it for us. “To a Vietnamese,” he writes, “all unions are the inescapable consequence of a debt contracted in a past life; when two human beings bind themselves to each other, they are only freeing themselves of a mutual burden.”

Thus, the paths of the girl and the fisherman were predestined to cross. Since they were never united in life, the “debt” followed the fisherman into his grave. As Pham saw it, the stone is not merely a symbol of the fisherman’s undying love: it represents “the whole man, his form beyond the grave, the face of an unrealized destiny which necessarily had to crystallize in view of the necessity of waiting”.

When the girl peers into the cup, she feels a great sadness at having missed the opportunity to fulfil her destiny. She senses the unpaid debt, and recognises that “their union must inevitably be accomplished”. “The cup received the tear which fell from her eyes and melted there in a communion which liberated them both.”

From an ambiguous and open-ended story Pham drew firm and specific conclusions, obviously rooted in the tenets of Buddhism. We can be sure, from its placement in the book as well as the fact that he had previously narrated it over a French radio broadcast, that Pham believed this fable to have a special importance. He was intent on sharing it with French audiences. It’s possible that he saw a universality in its themes and morals that could go some way in bridging the divide between cultures. More likely, however, he saw it as being distinctly Vietnamese, and thus a key that could be used to unlock the traditions and sensibilities of his original culture, which could then be imparted to, and appreciated by, his adopted one. The same, of course, can be said of Legends as a whole.

Notably, the most interesting — and certainly the most poignant — “legend” in the book is a purely autobiographical one. “My Grandmother’s Betel Box” is the last story in the collection, and the one that most underscores Pham’s deep and abiding attachment to his ancestral heritage. Here he reflects on the sorrow he observed in his grandmother after his father, her son, passed away (Pham was a teenager at the time): “Not only did my grandmother not go out [of the house], but each time someone came who reminded her of my father, she began to weep copiously, so much so that people eventually stopped coming.”

At the end of the previous story, Pham educates the reader on the traditional use of betel leaves in Vietnamese culture. Along with areca nuts, the leaves were part and parcel of romantic relationships. If a man proposed to a woman, he presented her with betel leaves. If the engagement was broken off, the leaves were returned. Pham likens them to an engagement ring.

But the leaves also had a broader ceremonial application. “In the past, you would not have been able to enter a Vietnamese house without finding, on a stand, a large round box … which would be offered to you as soon as you sat down.” The box contained “all of the accessories and elements necessary for chewing betel”. Pham goes on to lament the custom’s gradual decline in his lifetime. “Our young ladies … no longer concern themselves with the obsolete art of arranging a platter of betel,” he writes, adding that “young men no longer offer them a sturdy branch of areca nuts enlaced with a fresh sprig of betel as a pledge of their true love.” These words were written in the 1940s; it’s safe to assume betel leaves have all but disappeared from Vietnamese culture by now.

Musing on his grandmother’s plight, Pham recalls how her betel box enabled him to fully apprehend the sadness that characterised the final years of her life: “I saw, with the inner eyes of my heart in tears, my grandmother preparing the tray, arranging the small compartments of the lacquered wooden box with carefully rolled green leaves, areca nuts cut in equal sized quarters, without forgetting the thin strips of a particular ‘root’ … She lacked many things, but she always kept a fresh supply of betel, and no one ever came to share it.”

One reads the foregoing and regrets that Pham didn’t leave behind a memoir.

Finally, in a frank admission that foreshadows the last decision he made in his life, Pham writes, “I have promised to look after the box and that is one of the pretexts that I have for continuing my meaningless existence in this boring world.” Perhaps, in search of some antidote to the monotony of modern life, Pham sought refuge in the mystic representations of the distant past. Hence, Legends from Serene Lands.

The world may be boring, but Pham Duy Khiem was not. That’s something.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Indochina, Michael Howard, Pham Duy Khiem, Vietnam