The World of a Tiny Insect: A Memoir of the Taiping Rebellion and its Aftermath was written thirty years after a scarring childhood experience, which haunted the author throughout his life. As a seven-year-old, Zhang Daye witnessed people burnt alive and parents murdering their own children—traumatic memories that he recounts in visceral detail in the book. What he describes may not be representative of everyone who lived through that time, but the emotional depth of Xiaofei Tan’s prosaic translation, published in 2014, gives readers a precious glimpse into life amid violence in mid-nineteenth century China.

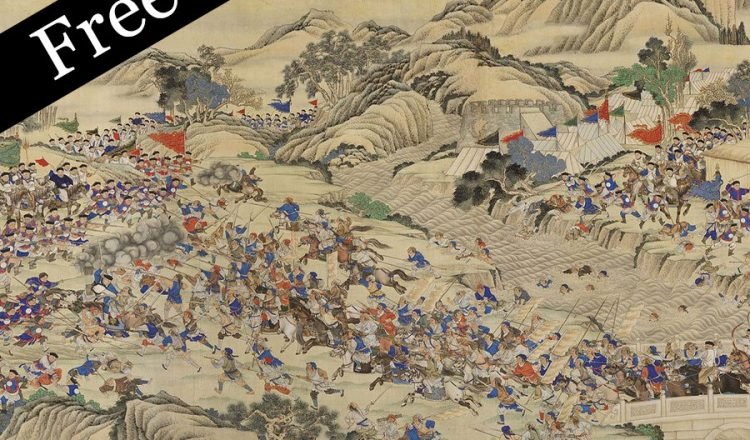

Its founding prophet, Hong Xiuquan, entered weeks of visions upon repeatedly failing life-defining imperial examinations. From his reading of a rediscovered translation of Christian scripture, he interpreted these visions as telling him that he was the younger brother of Jesus, with a mission to convert China to Christianity. His preaching spread across southern China, a region then suffering from economic crisis and weak government control. Hong and his followers sought to overthrow the Qing government and convert the people to their own version of Christianity. The authorities clamped down; the situation escalated into full-blown civil war. The conflict lasted for over ten years, at the cost of tens of millions of lives, making it one of the bloodiest civil conflicts in human history.

This World of a Tiny Insect isn’t an objective account, but an act of remembering. The way Zhang flits between past and present, clearly avoiding a chronological structure, makes this clear. And the trauma of a child, who “knew no fear” but trembled upon seeing “guts spilling out” of a weeping infant killed out of necessity by a father, follows him. This is present in the partiality of his account, which maintains a hatred for the brutality of the Taiping whilst overlooking that of Qing forces. His appreciation of the natural beauty he charts in his poems also seems enhanced by his childhood brushes with death. Few accounts of war pay so much attention to its impact on young children. But an impressionable Zhang bore deeper scars than the adults who protected him in his formative years.

One poem, in particular, reflects his struggle with his experience.

Tipsy with wine, face flushed;

But when all the singing is done,

………who can bring consolation

…………………for all the things one has witnessed?

At the end of the road, how much repressed resentment?

In this drifting life, how many dusty burdens?

Everything is murky and gloomy,

……..bright only for a moment,

………………..and dim again.

The civil war is estimated to have claimed up to 40 million lives, with mass looting, murder and rape leaving great devastation in its wake. Zhang places this on a micro level, illustrating how in the case of his village—and the thousands like it across China—such violence was commonplace. From accounts of kidnapping to descriptions of rivers filled with floating corpses, the extent of the pain and damage Zhang recalls overwhelms the reader with a vision of an apocalyptic world of hair-raising proportions.

The memoir probes important questions of the rebellion, too. Zhang doubts the sincerity of faith of many of the Taiping fighters, and points to the role of coercion or economic necessity in prompting people to join the rebels. This casts doubt on narratives that ascribe sincere religious evangelism as the main motivation for the rebellion. Meanwhile, Zhang’s traumatised reflections emphasise the often overlooked emotional, yet long-term, impact of war. The horrors of war, carved deep into people’s psyches, made it difficult for the Qing dynasty to regain much popular confidence even after the rebellion. The devastation, from which parts of China would not recover until the twentieth century, was simply unforgettable.

But to focus solely on the rebellion would be to ignore the richness of Zhang’s memoir. His evocative poetry serves as a reminder of the importance of this art form in Imperial China, and his portrayals of locations like Hangzhou’s West Lake bring out the undisturbed beauty of locations now much changed by commerce and industry. Such portrayals of nature give readers a much deeper sense of Zhang’s world. His references to Confucian classics—aided by our translator’s explanatory footnotes—show readers as exemplified by his allusion to the Zhuangzi to interpret the self-sacrifice of the “one-headed woman”. This is a portrait of a lost world in high definition.

Zhang’s lyrical descriptions give us a sound of this vast world, one ignited by another individual who began as a mere tiny insect: Hong Xiuquan, the failed scholar who became a Taiping leader and prophet. Hopefully, the rediscovery of this memoir lifts Zhang status somewhat beyond that he gives himself, as it has established itself as the leading English-language memoir of the rebellion. This microhistory is of relevance to both scholars of the rebellion and general readers, who will find much to be learnt about Imperial China and the experience of war within these pages. We are indebted to Xiaofei Tan for bringing to light such an illuminating text.

![]()

- Tags: China, Free to read, Oliver Green, Zhang Daye