x

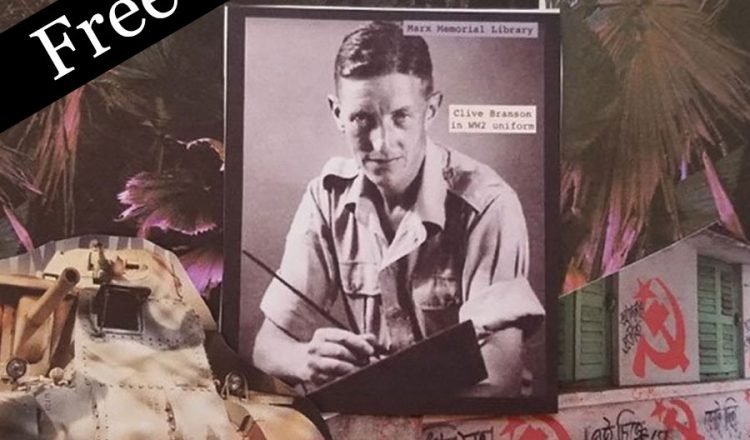

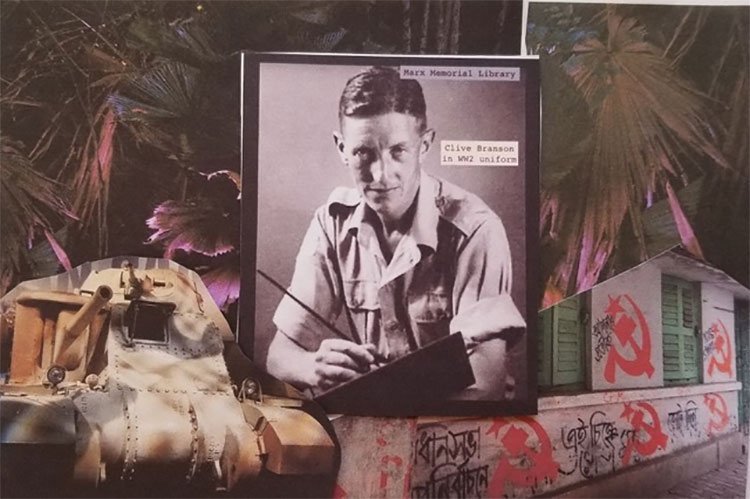

How antifascist would you be, to volunteer with the International Brigades against Franco/Mussolini/Hitler in the Spanish Civil War, survive months as a prisoner of war, then a few years later fight against Japan’s Imperial Army as a tank commander in Burma? And die there, at the end of a crucial battle known as the Admin Box, in a place called Arakan. If you were Clive Ali Chimmo Branson, painter and poet, you would be very antifascist indeed.

I found my way to researching the life and in particular the death of Clive Branson when I was writing Drawing Soldiers in Burma: Reflections on the War Artists which centred on the experiences of British artist Anthony Gross in World War II Burma. Searching for more war art, I noticed a startling picture called ‘Bombed Women and Searchlights’. I learned that the artist who painted it was Clive Branson, and that he was killed in action in Burma. This drew me in because I’ve been involved for decades with the liberation struggle of Burma (Myanmar), which is a continuation of events and alliances from World War II. The more I read about Clive, the more I wanted to know what led him to his Burma grave. Along the way I found more extraordinary paintings, Spain, India, poetry and a love story.

The son of the conjurer

The first important fact about Clive Ali Chimmo Branson is that he was born in India. Branson family history in India dates back to the 1790s, steeped in colonial mercantilism and the British-instituted legal system. Several British Branson men settled in Madras (now Chennai) and elsewhere in India. At least one bride of mixed Anglo-Indian parentage, Eliza Reddy, married into the family. The unconventional airline mogul Richard Branson was informed of this Indian ancestry by Henry Louis Gates on the TV show Finding Your Roots and appeared quite surprised.

Richard Branson’s great-great-great-grandfather Harry Wilkins Branson II, who married Eliza Reddy, was a stepbrother of Clive Branson’s great-great-grandfather. Clive was not a direct descendant of Eliza Reddy and may not have known about Indian intermarriage among the Bransons, but certainly he carried a deep personal connection to India that would influence his life.

Clive’s father Lionel Branson—married to Emily Chimmo, daughter of a British Hong Kong banker—was serving as an officer in the British colonial Indian Army in 1907 when Clive, the oldest of three sons, was born in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra. Clive’s middle name was Ali after the nickname of his godfather, Lionel’s college friend Prince Alfonso de Orleans of Spain.

Lionel described himself as a conjurer. His consuming interests were sleight-of-hand magic tricks and exposing fashionable spirit-mediums. He was also obsessed with debunking “the Indian Rope Trick”, in which a boy climbs a levitating rope. Lionel’s memoir, A Lifetime of Deception, gleefully recalls bamboozling shopkeepers, Rajahs and Afghan raiders with his clever ruses. The family fortunes fluctuated wildly and Lionel’s theatrical conjuring was as often for rent and tuition money as for charity.

Wealth and prestige shimmered on both the Branson and Chimmo sides but also spendthrifts (Lionel’s extravagant mother), scandal (the trial of the French lover of Lionel’s adopted sister Olive Branson, a murdered artist) and eccentricity (Lionel’s cousin Jim Branson gained some fame as a proponent of eating grass and other foraged vegetation.) Ill-fated polar explorer Robert Scott was related to the Bransons. Another of Lionel’s cousins, George Branson, was a barrister for the treason prosecution of renowned Irish nationalist and human rights activist Roger Casement—a case which ended with Casement’s hanging.

Like many India-born British children, Clive was shipped off to school in England. The school fees were a hardship; between windfall inheritances, the family lived in rental houses and travelled third class. Lionel’s memoir contains few mentions of his oldest son. The Spanish Civil War is not mentioned and Clive’s death only gets two sentences following several paragraphs about his brother Cyril’s appearance in the Noel Coward World War II movie In Which We Serve. Maybe Clive’s loss was too painful to dwell on in a light-hearted conjuring memoir.

In Lionel’s memoir Clive’s brothers are praised for their conjuring abilities but there seems to have been no interest in that from Clive. He looked for enchantment elsewhere, mainly in drawing. Described as good at chess, cricket and shooting but a bad reader, he perhaps had the dyslexia afflicting other Bransons.

Not Oxbridge or Sandhurst material, Clive was nudged into an insurance job which he quickly shed, instead enrolling in the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art. A couple of his paintings were exhibited by the very mainstream arbiter of taste, the Royal Academy. He formed lasting friendships at the Slade but grew to dislike its academic and careerist instruction and dropped out. Corruption of art by commerce made him take a suspicious view of capitalism and start searching for alternatives. The young bohemian began disappearing from any predictable path expected of him.

Class traitor comrades

Then Clive met Noreen Browne, a classically trained singer and musician.

She was the granddaughter of Henry Browne, 5th Marquess of Sligo—Anglo-Irish aristocracy. Henry Browne was in the Bengal Civil Service, so Noreen’s family background was privileged in both Ireland and India. In their favour, the Browne family were descendants of Irish pirate Grace O’Malley and Noreen’s great-grandfather Howe Peter Browne, 2nd Marquess of Sligo, Earl of Altamont, pal of Byron, was the abolitionist ‘Champion of the Slaves’ of Jamaica and a major activist for relief during the Great Irish Famine.

Noreen’s father, India-born Lt. Col. Lord Alfred Browne was killed in France in World War I and her mother Cicely Wormald Browne died of typhoid fever the same month in 1918. Noreen became deeply anti-war but was not otherwise political when Clive walked into her life at a charity concert. An immediate connection was forged in an all-night cafe conversation. This handsome couple (angular features, expressive eyes, his hair slicked back, hers bobbed short) married in June 1931.

Such a marriage might have been considered a triumph for the upper classes that Clive and Noreen would devote their lives to overthrowing. The newlyweds didn’t adopt phoney working class signifiers, keeping accents described as aristocratic, but they set out to be class traitors in more meaningful ways: renting a flat in left-leaning Battersea, giving away much of their inheritances and helping neighbours fight evictions.

Clive and Noreen became disillusioned with Labour and Independent Labour politicians over India, which the couple believed had to be freed from Britain’s colonial rule. Noreen suggested joining the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and Clive prepared by studying Lenin’s writings, which would have been slow-going if he did have a reading disability. When they joined the CPGB in 1932, Clive gave up painting for worker organising, although he had fifty red-covered copies printed of a book of his poems.

Some in CPGB were wary of the Bransons’ class backgrounds, but as Noreen would recall in an Imperial War Museum (IWM) oral history interview, “Clive got over that with almost everybody. He was very good with people. People always couldn’t help liking him.” Clive’s obituary in The Volunteer for Liberty (a Spanish Civil War International Brigades magazine) would call him “an inspiring and entertaining teacher who could rouse every type of audience to discuss and to learn. As one trade unionist put it after Clive had spoken at his branch: ‘I’d rather listen to that fellow than go to the pictures.’” CPGB leader Harry Pollitt, in his introduction to a collection of Clive’s letters, would recall his activist energy: “Nothing was too much for him: selling the Daily Worker at Clapham Junction, house-to-house canvassing… getting justice done.”

The Bransons helped drum up resistance to incursions of the British fascist Oswald Mosley and his Brown Shirt followers in disadvantaged neighbourhoods of London, including the Jewish East End. The mayhem caused by those Brown Shirts convinced the Bransons and many others in the British left of the need to fight fascism everywhere.

In 1933, the Bransons’ daughter was born, named Rosa after Marxist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg. A year later, Noreen travelled to India on a clandestine CPGB mission carrying funding and documents for Indian Communists. She used her aristocratic persona as a cover and evaded the colonial authorities. Noreen made other secret missions to Communist groups in Europe. During her mother’s espionage exploits, Rosa was sent to boarding schools at an extremely young age, an echo of Clive’s colonial childhood. Before long, her father would also vanish to a foreign land.

The Spanish prisoner

An elected government, the Spanish Republic, was attacked by Nationalist forces in July 1936. Communists and anarchists were among Spain’s Loyalist masses resisting the fascist Nationalists. Hitler and Mussolini sent troops, planes, tanks and weapons to help Nationalist leader Francisco Franco. Most other countries, including the US and Britain, opted for a ‘both sides’ non-intervention which benefitted Franco by choking off possible help for the Loyalists.

Volunteers from over fifty countries decided to go fight fascism in Spain with the International Brigades and other groups. Supplies were short and casualties enormous. But as Noreen, who raised funds for medical aid, told her IWM interviewer, “It was perfectly clear that if you saw what was happening you felt you had to do something about it.” On behalf of the CPGB, Clive arranged passage for many British volunteers: medical exams, tickets to Paris, boots for crossing the Pyrenees, all illegal and covert.

Clive had been in Spain in the late 1920s on a painting trip and was an excellent shot in Officers’ Training Corps during school. Noreen described him as “big and strong”. When police surveillance compromised his role as a facilitator for International Brigade volunteers, he enlisted himself, arriving in record-cold Spain in January 1938. After several weeks in Albaciete training camp he was sent, lacking even a rifle, to the front. He was put in charge of the twenty British volunteers of Major Atlee Company (International Brigade units were named for heroes like Abraham Lincoln or James Connolly, this one after the British Labour Party leader). By March, when the Brigaders were overrun in a battle, Clive—freezing, starving, and alone—had to evade fascist troops for a week to get back to Loyalist lines.

That Spanish winter was even colder on 31 March when a Loyalist battalion was attacked by Nationalist Italian tanks, which they had mistaken for their side’s Communist Russian tanks. Over a hundred of Atlee Company’s soldiers were captured, Clive among them. What followed is expressed in his poem titles: ‘On Being Questioned After Capture. Alcaniz’ and ‘Death Sentence Commuted to Thirty Years’. The Nationalists routinely executed prisoners, but this group was kept alive as bargaining chips. They were sent to a frigid stone prison, San Pedro. Clive’s ‘San Pedro’ was an ode to the lice-ridden, malnourished International Brigade men held there: “These men are giants chained down from the skies / To congregate and old and empty hell.”

Stephen Spender, who reported from Spain, later called it “a poet’s war.” Fascists executed Federico García Lorca soon after their putsch in 1936. Miguel Hernandez, a shepherd and a poet, fought in a Peasants’ Battalion and later died in prison. W.H. Auden’s poem ‘Spain’, based on his experience there, illuminated a kind of slideshow of history, struggle and the future, “the poets exploding like bombs”.

Clive wrote a stack of poems amid the brutality of San Pedro, and when transferred to a more humane Italian-run prison camp at Palencia. His verse was not at Auden’s or Spender’s literary level, but really better than most in The Penguin Book of Spanish Civil War Verse (poets writing in English), less overwrought and, for a communist, not heavy on the agitprop. Some rhyme, some don’t, and there’s a refreshingly modern turn to plain observation. “Like stones on stones / peeling potatoes,” he writes in ‘Prisoners’.

In the depths of San Pedro and at Palencia, Clive did very Clive things: generous, morale-boosting for his fellow internees. Using family connections, Noreen managed to send him money, which he used to buy tobacco and chocolate to be divided evenly among the prisoners. It was known that Clive’s godfather was Prince Alfonso de Orleans, then a squadron commander in the Spanish Fascist air force, but it’s unclear whether that resulted in any better treatment.

A fellow prisoner, Alec Tough wrote, “In any difficult times Clive was always cheery, putting forward what we should do, and helping to educate others in order to use the time usefully.” Clive helped start a lecture series and a prison newspaper. As CPGB comrade Margot Heinemann noted, “he became legendary for his ability to keep people’s spirits up despite the degrading conditions”. He conjured up an imaginary feast with his sketches of the inmates’ favourite foods. At Palencia he took advantage of an art-loving Italian commandant to obtain art materials and produced portraits of the prisoners which a British diplomat sent home, informing the CPGB and families that some of those deemed “missing in action” were alive.

‘By the Canal Castilla’, written at Palencia, where prisoners were allowed outdoors, reminds me of Wordsworth, a poet with revolutionary tendencies who Clive admired, in this stanza:

The guard’s bayonet splinters the sun.

A gilded Iris shrivels up.

A Poppy’s crimson cup

breaks petal by petal to the wind

That carries memories

of other trees, stretches of water, wings

After seven months in captivity, Clive crossed the French border, leading 100 British prisoners who had been exchanged for 300 Italians held by the Loyalists. Returning home, he went on a speaking tour in service of Aid for Spain.

“What upset him was when the war was lost. He had insomnia, was quite disturbed,” Noreen would recall. “He blamed our government.”

Spain, with its leftist infighting, ideological divides and ultimate defeat, did not disillusion Clive with communism. He seemed to have been more practical than doctrinaire in his allegiance. The Hitler-Stalin pact did make Clive and Noreen consider leaving the CPGB, but they stayed in and maintained their support once the Soviet Union was back in the fight against Nazi Germany.

Before he left for Spain, Clive had painted ‘Selling the ‘Daily Worker’ Outside Projectile Engineering Works’ and ‘Demonstration in Battersea, 1939’. He pictured working people and their brick surroundings with intensity and wit, in a wobbly perspective that reminds me of Balthus street scenes. In the Spain-supporting ‘Demonstration…’, a young mother seemingly tries to dissuade her eager-to-enlist husband, probably an echo of the Bransons’ own situation.

With these representations of his labour organising experiences, Clive is thought to have been influenced by the amateur coal town Ashington Art Group. But unlike those ‘Pitmen Painters’, Clive used sophisticated colour choices with flashes of red banners, deft incorporation of text and conspicuously well-trained brushwork. He showed his work at Lefevre Galleries, not exactly the workers’ hall, but an elite venue that would later represent Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud.

In Spain, Clive painted a few sunlit pictures of the second, ‘nicer’ prison camp. He recovered afterwards with painting forays to rural England. CPGB leader Pollitt wrote that Clive “spent a number of months painting very intensively, because, as he said, ‘it may be my last chance.’” His affectionate 1940 portrait of Noreen and Rosa showed them reading a Left Book Club volume on Spain. A still life juxtaposed a straw shopping basket and groceries with red-covered books, including Marx’s Capital.

What the Aid for Spain campaigners had warned about (“If you tolerate this your children will be next”) came true: Nazi Germany’s air raids over London. Clive was arrested when speaking out against the government’s inadequate air defence preparation. Noreen joined the plucky ranks of helmeted, gas-masked air raid wardens.

Clive painted his masterpieces (now in the Tate): wild swirls of action called ‘Bombed Women and Searchlights’ and ‘Blitz: Plane Flying’. His paintings had become surreal. Not Surrealist dreamy surreal, but everyday life thrown completely off-kilter surreal. Noreen is in ‘Bombed Women’ grimacing as she helps carry something heavy in a blanket while barrage balloons—tethered to snare German bombers—bob absurdly in the night sky, smashed objects become barricades and a poster proclaims “Dig for Victory!”

That must be Noreen again, with that straw grocery bag, in ‘Blitz’, a giantess pausing at the corner of a blasted street trying to repair itself. Like a perched hawk, a bomber looms against a cloud-smudged sky: is it one of theirs or one of ours? It has both Nazi and British insignia, perhaps an echo of the mistaken enemy tanks in Spain, perhaps the horrifying confusion of the moment the war came home. At that point in his painting life Clive was great, like early Philip Guston was great, with promise of astounding developments later.

Clive was writing as well as painting and his 1940 poem ‘International’ stared forward:

But everything new that I meet,

No matter how strange and uncertain,

Holds something familiar that

Proves the fight is still on.

Most International Brigades veterans stayed politically active after the Spain defeat. Some were hunted down or purged. Some lived on: I saw crowds part in awe when Abraham Lincoln Brigade veterans marched in 1970s New York demonstrations. For many, the 1930s bled into the 1940s as their personal war against fascism. If physically capable, they were determined to take up arms again.

My Bloody Valentine

Clive was conscripted in 1941 for a new chance to fight fascism, this time with the British Army. Many other British veterans of the International Brigades enlisted, although their military experience was usually devalued due to suspicions about their leftist politics. Some were denied enlistment even in civil defence units.

Submitting to authority during training was difficult for Clive, who had written in 1937 that the British Army was riddled with fascist leadership, and suggested reforms that included electing officers. Frustrating months were spent in a Royal Armoured Corps training camp becoming familiar with British Valentine light tanks which he wrote were believed “guaranteed to kill the fucking crew”. In his spare time, he followed the war news (loathing Churchill, cheering on the Soviet Union against Germany) and painted the surrounding English farmland.

Unlike Anthony Gross, Henry Moore, Eric Ravilious and many others mobilised to document the war rather than fight in it, Clive would not become an official war artist. Paintings of the Blitz that Clive submitted to a War Artists Exhibition were rejected by the Artists’ Advisory Committee. Tank commander Branson it was to be. His destination was India, next stop Burma, where British and Indian soldiers would face the occupying troops of the Japanese Empire. Fellow San Pedro inmate Jimmy Moon would remark on the number of Spanish Civil War veterans who ended up on the Burma front: “They thought we might desert to the Russians in Europe I think… too much of a coincidence.”

On his troop ship to India, Clive gave popular lectures about the Spanish Civil War. As Arnold Rattenbury noted in the London Review of Books, World War II British Army conscripts “included hunger marchers, stay-down miners, Left Book Clubbers, black-coffin bearers, China campaigners, India Leaguers, Howard Leaguers, associates of Artists International, International Brigaders, Trotskyites, Communists, pacifists failed by their tribunals.” Clive fit more than one of those categories and “found many friends” in the ranks.

India made Clive furious at the “howling disgrace” of systemic poverty and British imperialism. He used his leaves to meet with Indians opposing injustice and help them with editing and translation. He sketched people and places whenever he could. He wrote politically charged letters to Noreen, enclosing poems and descriptions of Indian culture made in hopes of writing a book on the history of art, signing off with “All my love, sweet comrade”. An Army censor told Clive how much he hated those letters.

Clive admired Indian poets including Toru Dutt, Sarojini Naidu and of course Tagore. He wrote an essay on contemporary English poetry, “especially Auden, Spender”, to be translated into Bengali. When asked to teach a class at a local co-educational school he chose to present poems by Wordsworth with observations on industrialisation, commerce, nature. Student questions like “how exactly did Wordsworth react to the French Revolution?” delighted him.

In India for over a year and a half, Clive was constantly aware that he should be fighting fascism, not polishing “boots, brasses, etc.” for parades. But he really used his time well, as a true ally and witness. He was acutely conscious of British racism and the imperial role in India, feeling it was his responsibility to subvert that while in his British uniform. He constantly stood up for local staff abused by soldiers, and patiently explained systemic oppression to even the most oblivious officers and other ranks.

Clive formed friendships with Indian artists and intellectual agitators amid the wonderfully caffeinated politics of coffee shops in Bombay and Calcutta and visited their homes. Like many Indian anti-imperialists, including communists, Clive believed that supporting the British military effort to defeat Japan’s expanding fascist empire was absolutely necessary. But Indian independence would have to immediately follow the war.

A Spanish Civil War comrade also serving in the British Army, Tony Gilbert, recollected in an IWM interview: “I would arrive in Calcutta or Chittagong or Bombay and have discussions with political leaders, members of the Congress Party, members of the Communist Party and sometimes the very leadership of both. And I’d be told that Clive was there only a week previously.” A “rank and file” Indian in Bombay gave Clive a postcard of “Joe” (Stalin) inscribed “with red greetings” and Clive promised to put it up in his tank. At that time Stalin was leading a heroic military struggle against Hitler. Stalin was also a devouring villain of murderous intent and execution, another genocidaire.

Clive’s letters to Noreen included notes on political-economic injustices, including most notably the Bengal Famine. In August 1943 he wrote about starvation and profiteering in Bengal (the region where Calcutta, now Kolkata, is located.) He condemned “the hoarders, the big grain merchants, the landlords and the bureaucrats who have engineered the famine” and recommended that England send food relief ships. This did not happen: ships were held for the war in Europe and the Bengal Famine ended up scything as many as three million Indian lives.

Like Roger Casement in the Congo and Peru, Clive documented a human rights catastrophe first-hand in India, observing on a “nightmare” train journey to Calcutta, “one long trail of starving people”, “almost fleshless skeletons, their clothes grey with dust from wandering”, “for miles, little children naked, with inflated bellies stuck on stick-like legs, held up empty tins towards us”. Ultimately Clive believed in land reform and “a permanent basis of financial aid to the peasants” to end India’s extreme food insecurity.

During the twentieth century, other massive famines resulted from twisted authoritarian versions of the very political theories Clive cherished. His hero Stalin’s berserk forced collectivisation starved millions to death in Ukraine and elsewhere in the Soviet Union during the early 1930s. Mao Zedong’s deadly ironic 1958–1962 Great Leap Forward collectivisation campaign caused tens of millions of Chinese peasants to die of starvation. Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge caused starvation which killed an estimated 10 to 20 per cent of the population in 1975–79. The 1983–85 Ethiopia famine combined a drought with mass war crimes of an authoritarian leftist regime.

For a while in 1943, Clive had been posted in his birthplace, Ahmednagar, as a gunnery instructor. It didn’t last—his politics seem to be the reason—but he was returned to his tank regiment, the 25th Dragoons, with a sergeant’s rank. It was with the Dragoons that he rode that train through famished lands to Calcutta, drawing closer to Burma.

![]()