Massacre in the Clouds: An American Atrocity and the Erasure of History

Kim A. Wagner

PublicAffairs: 2024

.

In February 2016, Donald Trump took to the stage at a rally in North Charleston, South Carolina, the night before the state’s primary. The field for the Republican nomination was still crowded with challengers who, in the coming months, Trump would boorishly pick off en route to the White House.

Trump, who’d declared earlier in the week that “torture works” in the fight against terrorism, bashed his fellow candidates for not embracing widely condemned techniques, like waterboarding, as fervently as he did. He launched into a grim and meandering tale, supposedly about General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing. For years, stories circulated online about Pershing’s troops shooting Muslims with bullets dipped in pigs’ blood—an animal considered unclean in Islam—while crushing a rebellion in the predominantly Muslim Moro Province of the Philippines after the Spanish–American War.

“They were having terrorism problems, just like we do,” Trump said. “And he caught fifty terrorists who did tremendous damage and killed many people. And he took the fifty terrorists, and he took fifty men and he dipped fifty bullets in pigs’ blood—you heard that, right? He took fifty bullets, and he dipped them in pigs’ blood. And he had his men load his rifles, and he lined up the fifty people, and they shot forty-nine of those people. And the fiftieth person, he said: ‘You go back to your people and you tell them what happened.’ And for twenty-five years, there wasn’t a problem. Okay? Twenty-five years, there wasn’t a problem.” (Trump would cite the story again a year later on Twitter, inexplicably adding ten years to the supposed period of peace.)

At the time, there was still a hopeless naivety among members of the American media that fact-checking Trump’s incessant lies would scuttle his nascent political career. Politifact checked with eight historians and found that “most expressed scepticism” about the Pershing story. A fact-check by the website Snopes years earlier declared a version of the story false. Republican Senator Marco Rubio, then still a nomination hopeful, questioned the tale’s truthfulness before adding, “That’s not what the United States is about.”

Trump’s diatribe also caught the attention of historian Kim A. Wagner, who cites it as one of the starting points of his book, Massacre in the Clouds: An American Atrocity and the Erasure of History. Wagner, a professor of global and imperial history at Queen Mary University of London, wasn’t so fixated on the veracity of the future president’s claims. Rather, he writes that “the real significance of Trump’s story was not that it was factually inaccurate but that it was so much closer to the truth than even his critics were willing to admit”.

Wagner, whose previous books document colonial India and the British Empire, describes how he “watched with disbelief as the worst Orientalist tropes about Islamic ‘fanaticism’ were resurrected and dusted off for redeployment in the twenty-first century—even as historians and other so-called experts insisted that it never happened.”

Trump’s display of violence, dishonesty and racism that night in South Carolina in part spurred Wagner to write an unsparing examination of one of the worst moments of the American empire: the massacre of Bud Dajo.

The incident took place in March 1906, when American forces surrounded and killed some 1,000 Moro men, women and children seeking refuge in the crater of Bud Dajo, a mountain on the island of Jolo in southwestern Philippines.

Wagner writes that he hopes to place the massacre among American atrocities like the Wounded Knee massacre of 1890 and, more recently, the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War. Both command a far greater place in American history than the largely forgotten—or, as Massacre in the Clouds convincingly argues, purposely erased—Bud Dajo slaughter. Wagner presents a masterful case for why the incident should be included alongside these acts of barbarity.

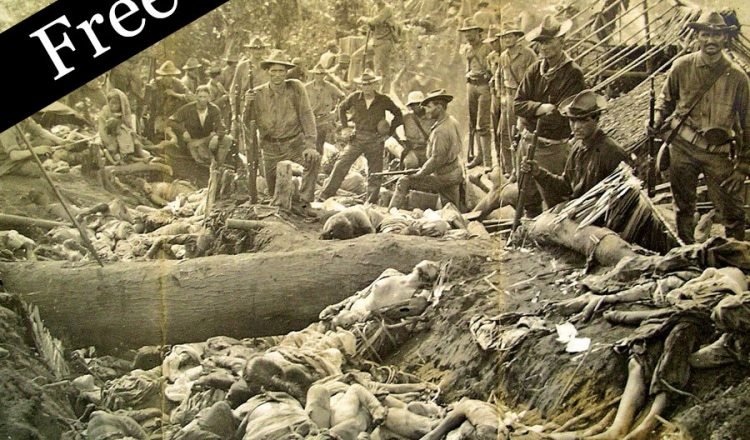

He accomplishes this by taking a novel approach to storytelling, centring the entire book on a single black-and-white photograph that captured the massacre’s aftermath. The picture shows a twisted heap of bodies piled in a trench, surrounded by American troops who stand like big game hunters posing over their trophies. “This book,” he writes in its early pages, “may accordingly be considered as a 100,000-word caption.”

The book begins by establishing the background of the US presence in the Philippines. Americans like to think that the worst and most cruel excesses of colonialism are reserved for the histories of the British or the French, but Wagner draws connections between American behaviour in the Philippines and tactics wielded by colonial powers elsewhere. By referencing the tools of repression—such as punitive campaigns of arson and destruction of livestock and crops—used in the Philippines, he demonstrates that the American presence in the country clearly fits within the broader evils of colonialism.

Massacre in the Clouds describes the lead up to the assault on Bud Dajo and the mission that followed. The Philippine–American War had ended four years prior, but Moro Province was put under military rule with American leaders believing the area needed to be “pacified” through a campaign of violence and forced assimilation. The first Moros began taking refuge on Bud Dajo in 1905, fleeing repression and natural disasters. The Americans saw it as a dangerous development, a hideout that would become a stronghold of thieves and criminals.

The three-day attack can be divided into two acts: the first of ineptitude, the second brutality. Both are meticulously recounted by Wagner, who draws on a variety of historical sources to re-create events. The US soldiers, struggling mightily in the heat and humidity, were hardly a picture of an elite fighting force as they started to take Bud Dajo. Communication was poor. Forces got lost and needed to backtrack. At one point, troops accidentally fired artillery at their own soldiers, killing two of them.

The barbarity that followed once they reached the Moros, Wagner writes, did not come from a sudden fit of rage or a series of mistakes made in the fog of war. There was a premediation to the slaughter. “They will probably have to be exterminated,” an American army captain wrote in the lead up to the assault. According to one officer, they “went under orders to fire on sight and take no prisoners”. Wagner’s writing is devoid of hyperbole; the horror of what took place stands on its own without any need for literary flourishes. Particularly ghastly is the book’s thorough recounting of US machine gunners mowing down unarmed women and children who had actually been trying to surrender.

While US officials and forces consistently used dehumanising language to describe the Moros, by the end of the massacre it was clear the Americans were the true savages. The cover-up began almost immediately. Major General Leonard Wood, the governor of Moro Province, stopped telegrams describing what had happened from being sent; instead, he issued his own with a heavily sanitised version of events. He visited the photographer who captured the aftermath and “accidentally” broke the negative in an attempt to keep it from circulating. The incident was pulled into a swirl of politics and partisan journalists. Some press even called reports of the atrocity “fake news”. The result, Wagner writes, is that “the story of Bud Dajo was transformed into a celebration of American rule in the Philippines”.

The second half of the book is an impressive and entertaining feat of journalistic sleuthing. Wagner details how he tracked down the identity of the photographer whose picture serves as the focal point of the book. Spoiler alert: readers hoping to find a person of moral courage, spurred to photograph the scene to bear witness and demand justice, will be sorely disappointed.

Richard Henry Gibbs, a former soldier who went by the name Aeronaut, comes across in Massacre in the Clouds as a sleazy opportunist whose primary concern was monetising the carnage by selling the photo as a macabre souvenir print and postcard. In fact, few people Wagner writes about—from journalists to politicians to military commanders—elicit anything but disgust and contempt. With few exceptions, they’re a loathsome bunch who saw Moro life as discardable and suffered no repercussions after disposing of them en masse.

Wagner writes of hearing Trump’s 2016 speech that “as I was busying myself with studying the past, the present had unexpectedly encroached upon my work”. It’s an experience that readers of Massacre in the Clouds will share, particularly with all the news of atrocities and massacres in various parts of the world—albeit ones that are US-backed rather than directly US-committed, as if that offers any measure of comfort. Wagner poses a prescient question at the start of the book. “How,” he asks, “can a nation perpetrate atrocities yet retain the conceit that it is acting as a force for good in the world?”

It shouldn’t be possible, yet America continues to tell itself otherwise.

![]()