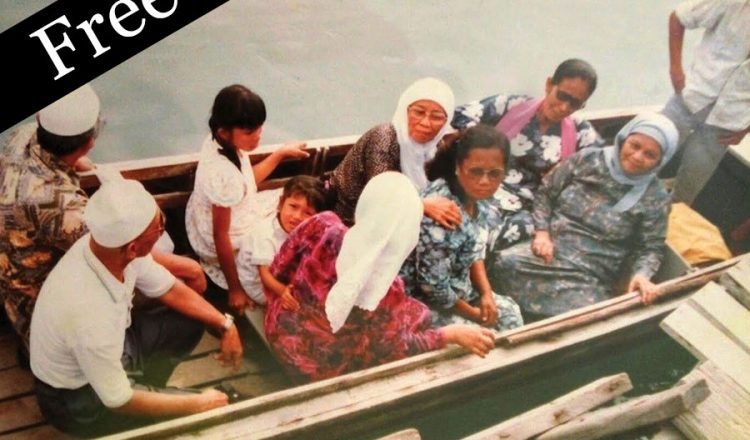

circa 1990, exact location unknown

On my last trip home to Singapore, I slipped in a two-hour ferry ride to visit relatives in Tanjung Pinang—specifically, Pulau Penyengat, once known for its immense literary and cultural contributions to the Malay world—in Kepulauan Riau. To Singaporeans, the Riau Islands are painted in caricatures: the site of your company’s awkward year-end getaway, the seedy haze of Batam affairs.

The Riau I know is the memory of my great-grandmother, Nyang, sitting on her sejadah (prayer mat). She’s holding a pungent bottle of minyak gamat (traditional medicinal oil) or hand-sewing another dress for one of my dolls, stitched together from scraps of fabric of a baju kurung (a traditional outfit of blouse and skirt). She is the satin-softness of her grey baju, her scent pillow-like—comforts only appreciated when they eventually drift away. Through Nyang, Tanjung Pinang lives as flashes in my mind, crystallising through faded photographs and family stories. On her sejadah, our histories floated—stories of homes, of loss, of where we are scattered and where we are ‘from’.

I say ‘from’ with tentativeness. It feels like an incomplete articulation of the deep kinship among communities of the Malay archipelago. ‘From’ too often implies a single, distant source, allowing presumptions about eventual detachment from a piece of land to run rampant. It supposes that a ‘to’ comes after: that at some point, maybe several generations ago, some ancestors moved ‘to’ Singapore, and that a line can be drawn to split Singapore from the islands that surround it.

Kepulauan Riau and Singapura are only separated if you conceive them through the edges of their land masses, of ‘land’ as nation-state territories. But land and sea hold much deeper stories when intertwined. There is an intimate relationship that birthed our Indigenous cultures, our food, our movements, ways of organising and being, and ourselves. Although thousands of years old, this relationship has been supplanted by harsher stories told over the past few centuries: stories of isolation, individuality and coloniality now calcified into the bones of dominant society.

In the early 2000s, Syazwan Majid’s mum brought him to Pulau Ubin—an island northeast of mainland Singapore—for the first time. He was only about six.

“She was cycling us through this area, and there was a particular shelter with some abandoned houses around. She dismounted from her bike, and went into the forest. Five minutes later, she came out. I asked her, ‘Why did you go inside?’ My mum said, ‘I was just trying to find my house.’”

It was his mother’s homecoming after almost two decades away from the island she grew up on. The Singapore Tourism Board now casts Pulau Ubin and similar spaces into the margins. Official portrayals dub them nature reserves to explore, where visitors can be transported back in time. But for many, like Syazwan’s family, it was home.

That first trip to Pulau Ubin marked the start of Syazwan’s years-long journey to connect with his ancestral island. Early attempts were prompted by childhood curiosity about the grandparents he had never met: “I kept asking my mum who my grandparents were, and she would always begin the stories with ‘Dahulu kat Ubin, selalu arwah Nenek kau buat ni, arwah Datuk kau buat tu [Back then on Ubin, your grandmother and grandfather used to do this or that]’. It would always be back on Ubin.”

Syazwan is now twenty-six and a social work undergraduate. He documents his discoveries and reflections on his blog, Wan’s Ubin Journal, and conducts tours around Ubin while confronting the myths still inextricable from dominant imaginations of Malayness.

Colonial conceptualisations of ‘the native’ seep into the ways Malay identity continues to be constructed. Syazwan notes the damaging effects of racial myth-making on the depictions of the kampung (a traditional Malay village): “This ‘Third World to First’ picture has always portrayed the kampung as ‘backwards’. They are haphazard. They are fire hazards. They are slums. They are disease-ridden. But our kampung houses aren’t built just tikam-tikam [randomly]. We build it in accordance to culture, to functions and roles. They’re more than just wooden structures: they’re a place, a memory and a living heritage that’s dying in Singapore right now.”

The denigration of the kampung is bound up with colonial and state governments justifying the destructive losses of Indigenous communities in Singapore, all in service of modern capitalism. The dissolving and vilification of native maritime communities, commenced by British colonisers, have continued past their rule over Singapore: between the 1960s and 1990s, rapid urbanisation by the republic’s government displaced thousands of native residents of surrounding islands, forcing a mass relocation to what is dubbed Singapore’s mainland.

Syazwan’s family were among those whose island-homelands were seized and gutted. “The Land Acquisition Act had, overnight, made the people of Pulau Ubin ‘squatters’,” he says. Suddenly, they were staying on ‘state land’.

Pulau Tekong, Pulau Senang and Pulau Sudong, once home to thousands of inhabitants, are now out of bounds. They are sites of militarisation, used by the Singapore Armed Forces to conduct live firing exercises. In 2015, some 150 of Sudong’s original inhabitants, by then elderly, petitioned to return to their homeland just for a day. It is not clear if their request was granted.

Pulau Semakau, where some Orang Laut (which translates to “people of the sea”) lived, was similarly seized by the government and transformed into a landfill. Generations of life were replaced with an incineration plant to burn the city-state’s ever-increasing waste. The islanders’ losses are seen, in the eyes of the state, as part of the master plan of urbanisation.

Since the start of the pandemic, a few descendants of Pulau Semakau have begun publicly documenting their family stories. Records of life—thriving, bountiful and fragrant—are immortalised on OrangLaut.sg, with occasional events bringing people together. This is now the nucleus for Semakau’s collective memories.

OrangLaut.sg archives traditional foraging practices and Orang Laut cuisines. Food has become their main vehicle for resurgence; they organise communal feasts and allow people to order set meals online. The Semakau of old can never be revived, but it lives on through elders and in intergenerational memory, stirred with zest and bittersweetness. Every dish that OrangLaut.sg prepares is resistance against attempts to wash away a peoples’ jiwa laut (spirit of the sea), serving up memories that might otherwise be buried under the ash of incinerated trash.

Indigenous resurgence has been described as, in part, imagining and living life beyond the state. For peoples whose collective and historic identities have been wiped or mangled through coloniality, remembrance can be a radical everyday practice of resurgence—habitual rejection of the violence of a society that routinely denies their ontologies. As Syazwan explains: “Every single house [on Pulau Ubin] had a person inside it. Who lived there? What did they do? What were their contributions, even if it was simple and mundane?

“When I bring people through the kampung in Pulau Ubin, I tell them about how this [house] is the home of a World War Two survivor. How he wishes that his final breath will be on Ubin. I tell them about the gotong royong (mutual aid) spirit, how a durian tree destroyed this other house, but the whole kampung came together to rebuild it.”

Remembrance like this is painful, and not done simply for the sake of dreamy nostalgia. To remember politically and ethically, despite the ways memory has been dismissed or commodified, is to be hopeful and future-focused. It is to never forget that the state itself memorialises.

Potent, prescriptive and purchased, the state’s memories are bound in our history textbooks and shallow racial harmony campaigns. State-engineered memories devise a social solidarity that emerges not from the land, seas and people it so often brutalises, but through pillars of bureaucracy, punitive laws and finger-wagging warnings of historical riots and a supposedly once-discordant national identity.

Indigenous memories are often positioned to confront this. Syazwan and his peers contest the cognitive imperialism baked into Singapore’s public education system—the one that tells us, for instance, that life began in 1819, when British colonisers arrived on these shores.

“We’ve been moulded to always think with a functionalist approach,” Syazwan says. “History and heritage will always be top-down, about the pragmatism of the People’s Action Party leadership, or of colonial powers. Like, is it too dangerous to talk about our Indigenous community?”

It is a devastating question answered by the structural racism that Malays and other ethnic minorities in Singapore battle with in a Chinese-dominated society. The ‘dangerous native’ trope, though shape-shifting over time, is one sticky strand of colonial racism. Ask a Singaporean for an understanding of Indigeneity and they are more likely to associate it with ethnonationalist politics (their cues coming from the politics of neighbouring Malaysia). Problems of colonial race-making in the archipelago, or the notions of decolonisation, anti-capitalism and abolition, are far more unfamiliar. And so Indigeneity—often reduced to the equally dangerous issue of ‘race’—is forced into a toothless symbol: formally constitutionalised and romanticised, but stripped of real political meaning.

The authoritarian context in which this plays out is not incidental. Even speaking truth to the violence of oppression in Singapore has consistently been met with denial and punishment. Here, the effects of Sara Ahmed’s famous quote—“when you expose a problem you pose a problem”—are legislated; even alluding to structural racism might result in being targeted by laws on the ‘promotion’ of ‘racial enmity’.

Indigenous resurgence gives us voice. It can remind us of worldviews bound by ethical relations between ourselves and the environments that birth our cultures and ways of being. When drawn to its radical conclusions, resurgence is deeply political because its practices are intimate and relational.

This resurgence is not about a state-sponsored manufacturing of ‘kampung spirit’. Government evocations of Indigenous values like ‘gotong royong’ are individualised, reducing the political spirit of collectivism and solidarity to singular, interpersonal acts; in this imagination, authoritarianism and capitalism remain the backdrop. Indigenous resurgence must reject assimilative politics that only allow Indigenous peoples to be recognised and legitimised so that they can be swallowed up by the state. Resurgence must do the work of repairing, healing and being accountable to one another rather than to the state, and of ethically remembering the implications of—and obligations we have to—‘place’.

In one chapter of The Food of Singapore Malays, Khir Johari’s mammoth collection, he describes how Malays forage and fish with clear pantang-larang (taboos and rituals). ‘Place’ is dense. It has more-than-human meanings, and life occasionally necessitates respectful intrusions into forests and seas—spaces that are not always ours to occupy. Khir explores how fishers had mantras to seek permission to ‘trespass’ into the sea spirits’ domains.

‘Place’ is a heavy web. It operates with an ethics of relation that the writer Diana Rahim hints at in ‘Transgression’, published in a collection of Malay speculative fiction, Singa-Pura-Pura. Her story is a retelling of a Malay folktale and its associated Ulek Mayang dance ritual: it is of a relationship between a human man and a sea princess. Their daughter, Cahaya, eventually learns of her mother’s origins. The story traces the beads between the human world in which Cahaya struggles to feel at home and the spiritual world of the sea, which her father grieves. ‘Place’ melts into the multiple spaces we inhabit and the makhluk halus—beings delicate enough to move through the gauzy membrane of worlds—that we live alongside.

‘Place’ is more than geographical. The Tongan and Fijian writer Epeli Hau‘ofa explored in his work how the sea binds and produces a “boundless world”. The sea was never an empty separator; it shimmers alive with the in-between. Less like the unmoving rock of our standard national stories, with their clearly marked beginnings and endings. Less like colonial identities, with their unyielding categories of nation, race and borders. More like waves, arriving, returning, arriving again. Indigenous ways take on a dynamism that is not simply rooted, but routed.

Syazwan puts it fittingly: “We always refer to home as ‘tanah air’—land and sea. These things… you just cannot separate them.”

Pulau Penyengat is often described as small. But it is only scaled down when violently yanked out of its place in the archipelago, as it was when Riau was colonised by the Dutch.

Colonial border impositions mean that Penyengat is today part of Indonesia, with families of maritime communities scattered across different nation-states. To paraphrase Frantz Fanon, their worlds were cut up by a colonial project that has been naturalised in our social, legal and political systems.

The writer Anisha Sankar describes the work of decolonial relations as “tending to the wounds” of colonial violence: our worlds, our places, our bodies, our forgotten memories. But forgetting is never permanent. Remembrance comes in waves. For me, this hope materialises in the thickness of an old, well-used sejadah. In knowing water as kin, a relative, neither a territory to acquire nor without its thicker, viscous meanings. In remembering my great-grandmother—stories murmured, minyak gamat or a needle and thread in hand—caring and tending to the gashes in our memories, restoring our understanding that we are not simply from but of these islands, and the waters in between.

![]()