.

Ship with Paper Sails, Story of a Hanoi Newsman

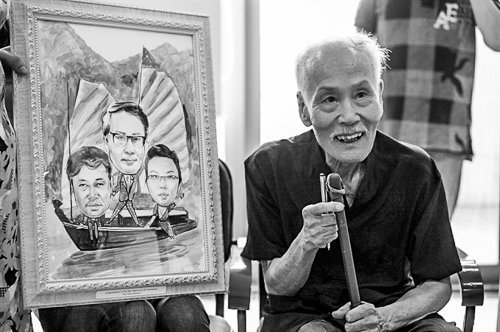

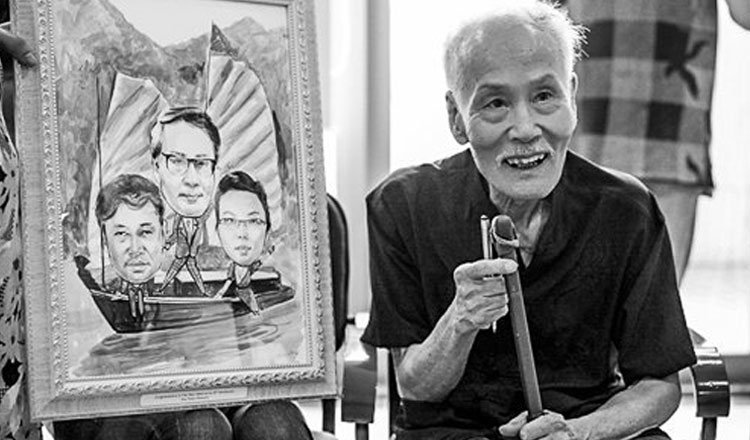

Nguyen Khuyen

Vietnam News Agency Publishing House: 2016 (not for commercial sale)

.

Evening has fallen on the Hanoi offices of Viet Nam News, the country’s only English-language daily paper, sometime in 2001. Most of the Vietnamese staff have already left for the day, while several of the half-dozen or so foreign sub-editors — myself included — have stayed back, as usual, to tweak the front-page stories and to write the headlines.

Under an enormous banner headline, tomorrow’s lead story relates a prime ministerial visit to a communist youth group in a remote province. This is a typical Viet Nam News front-page screamer. As is also typical, this breaking news took place two or three days ago — the time it took to select the story from the Vietnamese language press, reappraise its suitability for an international audience, and translate it.

The Vietnamese editor/translator has suggested the headline “PM Khai praises Gia Lai communist youth”, which is about twice as long as space permits. We can obviously remove “Khai” — there’s only one PM. “Praises” is a bit long, but “lauds” — an old standby — will save another smidgin of space. A debate ensues about whether to cut “Gia Lai” or “communist”. The readership is mostly Western, with limited knowledge of Vietnamese provincial geography, so the province name probably adds less to the story than the fact it was a communist youth group, rather than some other assemblage.

We sit looking at the screen. “PM lauds communist youth” looks back at us. It will satisfy the Vietnamese night editor, but we’re not happy. We are paid, after all, to make Viet Nam News look and feel like a Western newspaper. Our New Zealand colleague, who has his fingers on both the keyboard and the zeitgeist, types: “PM lauds bodacious youth”. We laugh, knowing we are never going to get a bit of ironic surfer slang from Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure onto the front page of a daily newspaper that takes itself very seriously. But it’s late, and we can’t think of anything else. We decide to see if we can get away with it. We print the proof.

A little while later, the Vietnamese deputy editor strolls over. He is a pleasant man, with the unpleasant task of being the “barbarian wrangler”. It is his job to tell the foreign staff when their rewrites of the Vietnamese reporters’ translations have crossed the invisible but very real boundary of the politically acceptable — conversations which often lead to vigorous debate, and occasionally to shouting, and general loss of face (mostly by the barbarians).

“Yes, yes,” he begins — his usual throat-clearing moment of enthusiasm before the difficult task ahead — “this word, bodacious, what does it mean?”

Although this was 2001, the first tech boom had largely passed Vietnam by. The office had a single hooked-up computer, its dial-up connection unreliable. So the deputy editor was heading for the office dictionary: two enormous, grey volumes, dating from the early 1970s, kept on their own ledge, and stamped “US Embassy Saigon”.

Legend had it that the founding editor of Viet Nam News, Nguyen Khuyen, who had recently retired, had been one of the first Vietnamese reporters to enter the US Embassy following the American evacuation in 1975. While others took photographs and combed the building for documents, Khuyen, whose passion was the English language, spotted the dictionaries and grabbed them as a souvenir. He lugged all seven or so kilograms back to Hanoi, where it now served the Vietnamese state in much the same way as it had probably assisted the former foe.

It’s unlikely this thirty-year-old dictionary will contain a word that only gained currency in a ten-year-old film. The deputy’s suspicions will be raised, and he will ask us to change it. But he comes back with the dictionary in hand, beaming. “Bodacious: nineteenth century word, mostly archaic, meaning excellent or of great merit,” he reads out. “This, I think, is a very good word.” And so it was. Bodacious made the front page.

The story about the acquisition of the US Embassy dictionary doesn’t get a mention in Nguyen Khuyen’s memoir, Ship with Paper Sails. He doesn’t, in fact, mention having reported from Saigon at all. Perhaps it was apocryphal — a lot of expat stories are.

Ship with Paper Sails, which is limited to a 400-edition print run, whips through his childhood in a few brief pages, then recounts — in what he himself accurately describes as “the terse style of a wire report” — the various tasks he took on during a lifetime of service to the Vietnam News Agency.

As an English-language graduate, his first job at VNA in the late 1950s was translating foreign wire stories into Vietnamese, but from the early 1960s his job was to rewrite Vietnamese news in English, and sometimes produce reportage in English, for an international audience — initially, presumably, anti-war sympathisers, but later (after Viet Nam News ’s founding in 1991) NGO workers, businesspeople and backpackers. While reporting from around Hanoi in the sixties he witnessed harrowing scenes of the aftermath of US bombing raids, and during a foray north he narrowly avoided death after being caught in a skirmish during the Vietnam- China war (the report of which he jotted down on the back of a cigarette packet as he travelled back to Hanoi).

During the war, his work meant long hours at the office in a largely evacuated Hanoi, separated from his wife and children and subsisting on rations (rice allocation was graded according to salary and age). His journalism classes for colleagues apparently marked him out as “an ambitious, self-seeking young Turk,” but he was undeterred by the “back-biting.” He was also upbraided for the friendships he struck up with Americans while on a work trip to Cuba, but told his critics that these were only Americans who had read Herbert Marcuse’s Repressive Tolerance.

In the end, he was trusted enough to be posted to Cambodia for three years as a correspondent during the early 1980s, and subsequently to found and edit Viet Nam News — clearly an impressive logistical and political feat — until being “informed of his retirement” in 1999.

Khuyen may never have swiped a pair of dictionaries in Saigon in 1975, but I suspect there are probably plenty of truer stories he has refrained from mentioning in this memoir. This, I think, is partly culture, partly pride and partly politics. There are some things better left unsaid. It was the same at Viet Nam News in my day. A young reporter once wrote an observational piece about the changing morals in Hanoi. It included the following rhetorical question: “Why is it, in Hanoi, that an act of love — two people kissing — is not permitted in public, yet men are allowed to piss in the street?” The editor-in-chief took exception.

For some reason — or possibly many, quite complex social and political reasons — discussions about what should and shouldn’t be in a story often ended up being discussions not between the Vietnamese reporters and their red-pen-wielding editors, but between these editors and the foreign sub-editors — who championed the reporters’ cause. Accordingly, I was summoned for a conversation with the barbarian wrangler. “Yes, yes. I don’t think we can say that men piss in the street in Hanoi,” he said.

Knowing the reporter was watching me from across the room, I argued that we really couldn’t alter a fact. Eventually the editor-in-chief himself was summoned. “But this is not a fact,” he said. “Men do not piss in the street in Hanoi.” I took him over to the window. We looked out on to the street below. Across the road, a man was watering the wall. The line was still removed.

Sometimes, it seemed to go the other way. One day, I was asked to edit an indignant refutation of an Amnesty International report critical of Vietnam. The article was going to lead page three, and the editor-in-chief came over to emphasise what an important story it was — these untruths and distortions had to be corrected. “But you’re just drawing attention to it,” I told him. He wasn’t convinced. I suppose silence may have been taken as admission of guilt, but in that pre-internet time most readers probably would have been blissfully ignorant of the Amnesty report’s very existence.

Khuyen’s memoir additionally contains a number of testimonials from foreign staff who worked with him at the paper. Their reflections reveal the range of motivations that drew people to it: some were orientalist scholars-in-training, some were communist to their bootstraps, some were passing through and some were washed up, both geographically and emotionally.

My then partner and I, both financial journalists, were sent by Australian Volunteers International with a brief not only to help with the sub-editing but also to do media training for an up-and-coming generation of Vietnamese reporters. These cadets were still basking in Khuyen’s apparently reformist fervour (he had just left by the time I arrived). Their keenness transcended the fact that their day job was largely translation, and that the newspaper’s demand for investigative and interviewing skills was relatively limited. There was also the issue of trust: the constant arguments we had with the barbarian wrangler over the mentionable versus the unmentionable led the editors to suspect our potential syllabus might be a bit subversive.

But the “bodacious” incident, which came about a year into our posting there, proved something of a turning point. The reaction of the deputy editor, and the readers, suggested that where direct confrontation had failed, perhaps satire might succeed. We couldn’t change the substance, but we could change the style. We began to over-write. Each day henceforth, Viet Nam News trumpeted a bracing fanfare of relentlessly positive over-spin.

Fifteen years later, reading Khuyen’s memoir, I feel a little remorseful about taking such liberties with a project that he ruined his health over. More than that, I wonder whether the newspaper today has found its own voice, and no longer looks for the sweeping retranslations into Anglo-Australian journalese that were our hallmark. The prose nowadays suggests an increasing editorial confidence — an ability to forge stylistic authenticity from a range of cultural influences, rather than simply mimicking the Western model for writing news. If so, then both Khuyen and I would probably laud the bodaciousness of that.

![]()

- Tags: Hans van Leeuwen, Issue 5, media