Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern

Jing Tsu

Riverhead Books: 2022

.

Has any invention defied so many grim prophecies as the Chinese typewriter? ‘Typewriters are now, it is said, made for the English, French, German, Spanish, Bohemian, Russian, Danish, Swedish, Portuguese and Italian languages. It is only with the Chinese, with its thirty thousand characters, that science is powerless.’ So declaimed Isaac Pitman, the language reformer and inventor of shorthand, in 1893. Such a statement carried the menacing weight of an implacable truth in the late nineteenth century. As Kingdom of Characters, by Jing Tsu, a professor of East Asian languages and literatures at Yale, shows, Pitman was not alone in holding such a belief. The famed Chinese writer Lu Xun similarly despaired, in 1936, that traditional Chinese script would lead to China’s downfall. As Tsu observes, ‘Alphabetic languages were lauded as the trains and automobiles of modernity, while the Chinese script trailed behind as the rickety oxcart’.

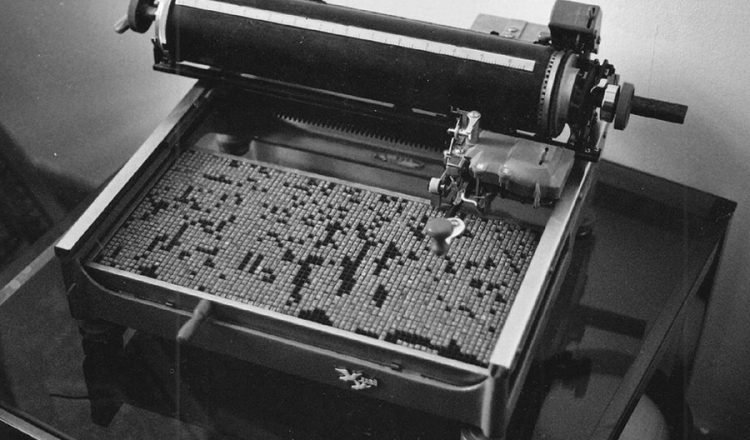

Had he lived past the new millennium, Pitman would have had to eat his words, for in the 1940s, a Chinese typewriter was unveiled to the US public. The ‘MingKwai’ or ‘Clear and Fast’ typewriter was invented by the bilingual philologist and cultural critic Lin Yutang, who devised a way to reconcile the Chinese ideograph and the Roman alphabet on a machine. News of this breakthrough was heralded as a cosmopolitan triumph in newspapers throughout the nation. At fourteen inches wide, eighteen inches deep and nine inches tall, the machine was about the same size as mid-century Western typewriter models. Kingdom of Characters assiduously tracks how the MingKwai went from gleam-in-the-eye idea to proof of concept.

- Tags: China, Issue 27, Jing Tsu, Rhoda Feng