On a stifling Sunday afternoon in Hong Kong last July, I walked down the hill from my apartment to the small public square outside my local district councillor’s office. There, I joined a queue—face masks on, appropriately socially distanced—and, along with some 600,000 of my fellow Hong Kong residents that weekend, cast my vote in a primary run-off election organised by the city’s pro-democracy opposition parties.

The purpose of the primary was to decide which pro-democracy candidate would run in each of the thirty-five democratically elected seats in the city’s legislature, in elections due to be held in September. Hong Kong’s pro-democracy politics is famously fractious and sometimes rowdy. The primary would avoid internal competition among the democrats and increase their chances of winning against the better-funded and unified pro-Beijing parties.

Alongside my neighbours, I verified my identity and residential address with the volunteers, was given a code to access the voting platform on my phone, and made my selection. As I did so, a lump rose in my throat. Despite everything—the months of protests that had riven the city in 2019, the ensuing government crackdown, the pandemic that had led to so much disruption and uncertainty—this was an act of hope. A shared belief that we could still make a difference. I thanked the volunteers for their efforts with the simple slogan of solidarity: 加油!Gaar-yau! (‘Add oil!’) We allowed ourselves a smile underneath our face masks.

The vote was taking place just a few weeks after Beijing had imposed a new National Security Law on the city, over the heads of the city’s own legislature. Overnight, Hong Kong had become a place where people were being arrested for acts of peaceful protest and political speech—chanting now-forbidden slogans, waving now-forbidden banners, singing now-forbidden songs. Teenagers were being dragged from their homes in the middle of the night and arrested for their Facebook posts. Then, the Hong Kong government warned that these primary elections themselves were an act of ‘subversion’, and that anyone participating in them might be committing a crime under the National Security Law.

Yet the turnout that weekend, far beyond the organisers’ expectations, was a very public rebuke, an act of defiance. In a year when no public protests or gatherings had been permitted due to pandemic restrictions, the event was a kind of virtual, distributed, 600,000-person protest march against the government and the National Security Law.

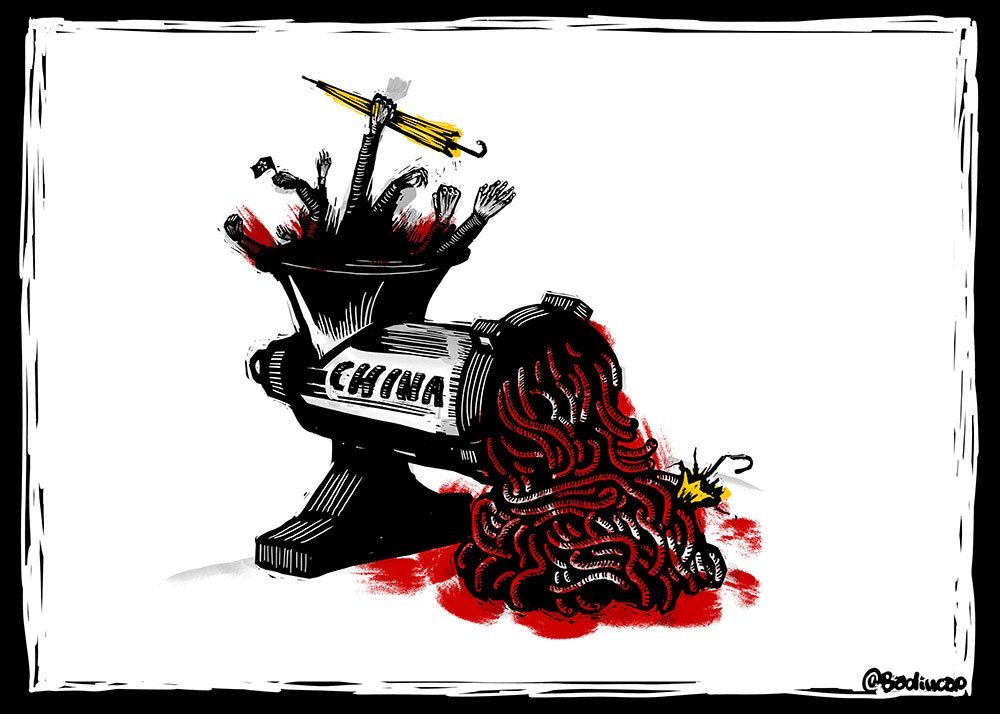

As subsequent months made clear, the National Security Law has fundamentally remade Hong Kong. Or unmade it. The law is being used to implement a radical reshaping of Hong Kong society as a whole, a wide-sweeping tool to create a climate of fear and shrink the civic space for anti-government groups and individuals, to exclude them from government, the education system, the media and civil society at large.

This past week, some six months after we voted on that July weekend, the Hong Kong authorities undertook the largest mass arrests yet under the National Security Law. Calling the primary election a ‘vicious plot’ that had the aim of winning a majority of seats in the legislature and ‘paralysing the government’, the authorities arrested fifty-five pro-democracy politicians and supporters for the crime of subversion. All of the candidates who ran in the primary were taken in, effectively arresting the entire political opposition in one fell swoop. Others arrested included academic Benny Tai who had proposed the idea, the organisers (including an American human rights lawyer in his seventies), and owners of businesses which had hosted polling stations. Media offices were served with warrants for documents and a law firm was raided by police. Robert Chung, a widely-respected public pollster who had provided the technology platform for the election was hauled in by police to assist with their investigations. The government statement blared: ‘The Hong Kong Government will not tolerate any offence of subversion.’

The security secretary, John Lee, sought to reassure the public that the arrests targeted only the ‘active players’ in the subversive plot. The police operation did not involve people who merely voted in election, he said. Was this supposed to make me—and my 600,000 fellow voters—feel relieved? Or perhaps grateful at being spared?

The September elections were ultimately called off, postponed for ‘at least a year’, due to public health considerations, the government said. Many suspected the real reason was a fear that the pan-democrats’ plan to win might have succeeded.

So, the moment of hope we all shared that July weekend is gone for now. Most of those arrested have been released on bail, their passports confiscated as they await formal charges. Protests continue to be banned. And the future of our elections, and Hong Kong’s once vigorous—if imperfect—democracy remains uncertain. You’ll forgive us if we no longer smile behind our masks.

![]()

- Tags: Antony Dapiran, Free to read, Hong Kong, Notebook