A friend had said there was a new boxing gym just past the Japanese Bridge in Phnom Penh. Paddy Carson, a former bare-knuckle champion from Durban, had recently moved from Pattaya, Thailand, and opened the Angkor Youth Boxing Club in a sweltering old warehouse on the northern edge of Cambodia’s capital.

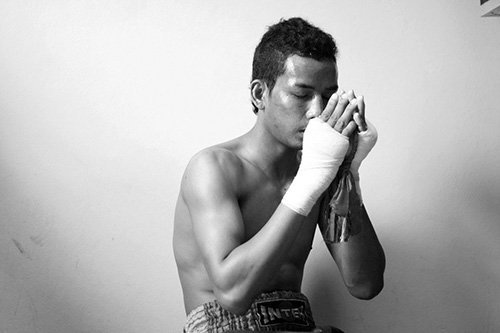

There, in the back, in a small ring with fraying ropes and a muddied blue canvas, Kru Paddy hammered the importance of straight punches and strong cardio into a dozen wiry young fighters with championship dreams.

In those days, circa 2006, local TV stations TV5 and CTN held (and broadcast) four Kun Khmer cards every weekend. Kun Khmer is the Cambodian version of what the world generally calls Muay Thai, although there is vehement disagreement between the two kingdoms over the naming, origins and ownership of the sport.

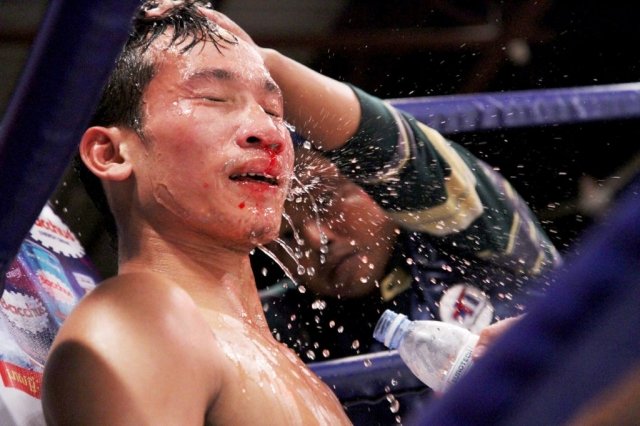

Kun Khmer cards at the two stations generally comprised between five and seven bouts, and you could see every fight live. The lighter divisions were stacked with rising stars. Foreign fighters made occasional appearances, too, but Cambodia’s long-simmering dispute with its neighbour meant that Muay Thai fighters remained unwelcome in local rings. (Cambodia still refuses to compete in Muay Thai at the Southeast Asian Games because of the name.)

By 2011, however, profit had finally trumped pride, and the Cambodian Boxing Federation rescinded its ban on Thai fighters. These days, five stations broadcast nearly 100 fights across the kingdom every week, and a thriving network of rural boxing rings continues to expand across the countryside. Later this month, Siem Reap will christen a new stadium to showcase Kun Khmer to the skyrocketing number of tourists who visit Angkor Wat. And Thai fighters are once again Kun Khmer’s number-one foil, just as they were in the early 1970s, when, (according to the old-timers, at least) Khmer fighters regularly “smashed” their Thai counterparts, to the pleasure of thousands of screaming fans.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Kun Khmer, Robert Starkweather