Red Memory: Living, Remembering and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution

Tania Branigan

Faber & Faber: 2023

.

History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.

—James Joyce, Ulysses

https://mekongreview.com/wp-admin/edit.php

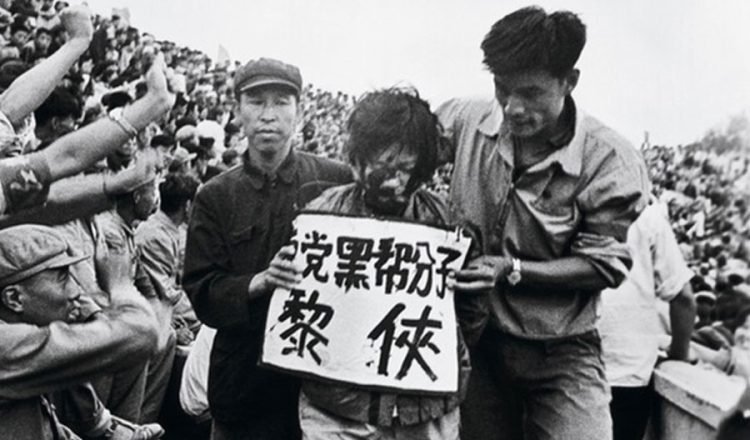

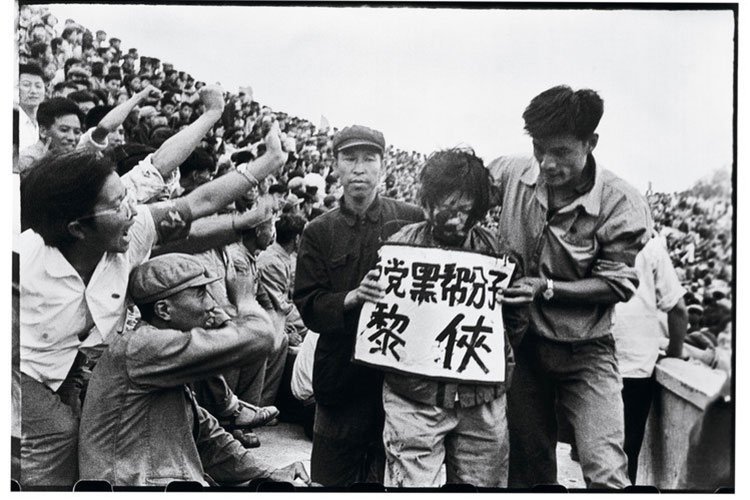

What a country doesn’t collectively talk about can often be more important than what it does. In China, the national conversation is undeniably top down, controlled through state media, an overtly politicised education system and local levels of control that reach down to the ubiquitous neighbourhood committees. Former Guardian China correspondent Tania Branigan’s much praised Red Memory: Living, Remembering and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution, a collection of interwoven stories of those caught up in the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976, reveals the complexities of remembering the most catastrophic event in the nearly seventy-five-year history of the People’s Republic. The Cultural Revolution is simultaneously there and not there; mentioned, yet not discussed; over, but far from resolved.

One might think, and Branigan would agree, that perhaps in 2023 the world has enough bad news and depressing stories. Readers might need a break. She admits Red Memory was not just a hard book to research and write, but also to sell and finally convince people to read. Yet, it has achieved that rare accolade of reaching out beyond the confined circles of Sinologists and China watchers. Red Memory is finding a far wider audience. The multiple stories Branigan tracks of differing participants, whether marginal or fanatic, perpetrators or victims of violence and humiliation, are the most human of stories.

- Tags: China, Issue 32, Paul French, Tania Branigan