Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World

Joshua Kurlantzick

Oxford University Press: 2022

.

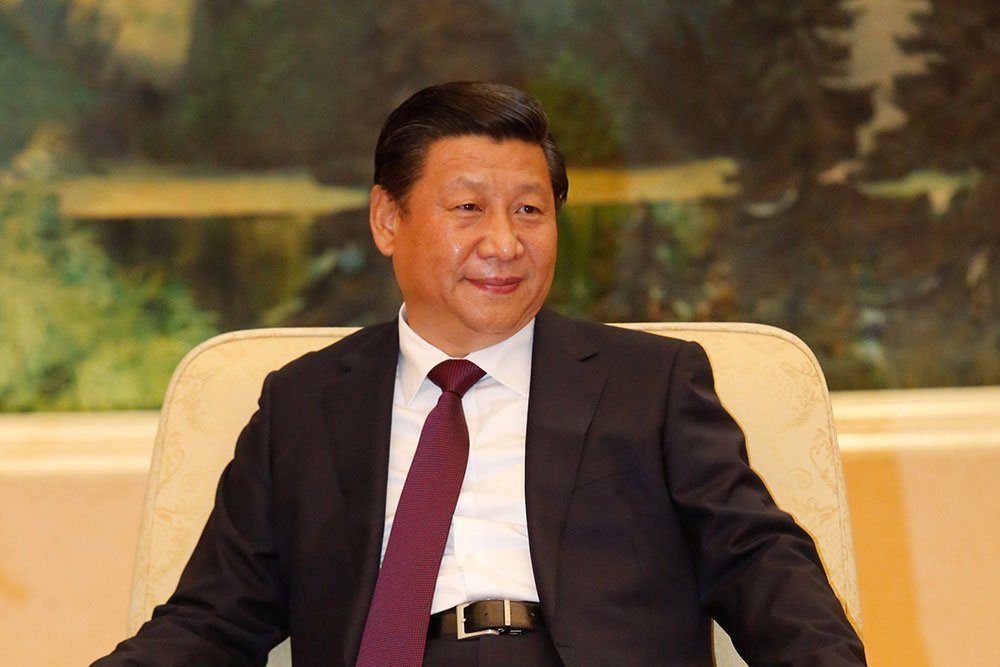

We do not need to chase [after other countries]—we are the road,” declared China’s leader Xi Jinping during a meeting with scientists on the island of Hainan. The tropical island hosts a massive naval fleet, shipyards and nuclear submarines, and was the site where Xi launched the country’s first domestically produced aircraft carrier, Shandong.

Contrary to prevailing international law, and in violation of the sovereign rights of many smaller nations, China claims the bulk of the South China Sea as part of its ‘blue national soil’ based on a concocted doctrine of ‘historic rights’. In 2013, China shocked the world by initiating an unprecedented geo-engineering campaign across disputed islands in the area. After a decade of aggressive land reclamation, a whole host of rocks, atolls and islets have been transformed into gigantic islands with state-of-the-art military bases and civilian facilities. But even that wasn’t impressive enough for Xi, who called on scientists to create an underwater sea base to consolidate China’s creeping domination of the disputed waters.

Xi’s triumphalist statement was not an isolated case of nationalist chutzpah. In stark contrast to his immediate predecessors, who downplayed the country’s newfound power, Xi has openly presented China as a potential role model for other developing nations as well as an agent of transformation on the global stage. At the nineteenth National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2017, Xi touted his country’s economic success as “a new option for nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. He extolled “Chinese wisdom and a Chinese approach to the problems facing mankind”, since “the banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics is now flying high and proud for all to see”. For any perspicacious observer, it was crystal clear that Xi was overseeing an overhaul of China’s domestic political landscape and foreign policy.

Bio:

- Tags: China, Issue 30, Joshua Kurlantzick, Richard Heydarian