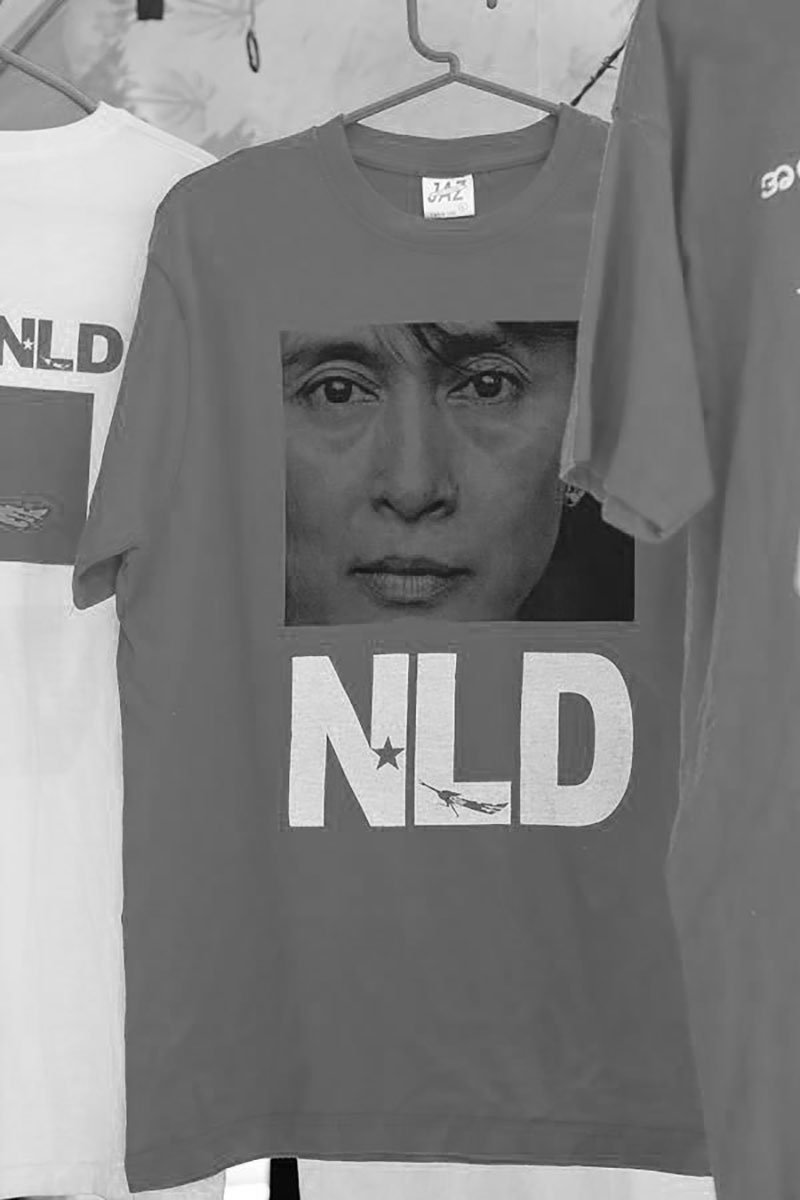

Democratic Transition in Myanmar: Challenges and the Way Forward (The 43rd Singapore Lecture)

Aung San Suu Kyi

ISEAS: 2018

.

Myanmar Transformed? People, Places and Politics

Justine Chambers, Gerard McCarthy, Nicholas Farrelly and Chit Win (Eds)

ISEAS: 2018

.

The outside world can choose the issues on which they wish to focus and, after Rakhine, the one that is attracting most interest today is foreign direct investment,” says Aung San Suu Kyi, or Daw Suu as she is known in Myanmar, in her 2018 Singapore Lecture. The people of Myanmar, having endured debilitating Western economic sanctions in the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, know all too well that human rights issues have to be sorted out — at least to a degree seen by the world as acceptable — if their country is to be fully integrated into the global economy.

Myanmar Transformed? is an edited volume of research papers presented at the Australian National University’s Myanmar Update conference in 2017, hailed as “the most thematically expansive conference of its kind since the Update series began in 1999”. The conference was attended by academics, researchers and policymakers from Myanmar and abroad, among whom was the prominent economist Dr Aung Tun Thet, representing Daw Suu. The book is one of the few on the country to feature Myanmar researchers alongside established and emergent scholars from elsewhere.

As expected, the book is delightfully diverse in its observations. The opening chapter, on village governance, by World Bank affiliates, is complemented by a chapter that pokes holes in the World Bank’s findings on agricultural mechanisation in Myanmar. One author claims that “whilst political freedom and freedom of expression have improved under the NLD [National League for Democracy] administration”; another says that “the NLD government in fact created a more restrictive environment for ‘civil society’ groups” than their predecessor, the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party. Variations on the theme of “the NLD’s centralized vision of power” are coherent throughout the book, however. Matthew Walton concludes that NLD’s governance has in effect become a “one-woman show” since its members of parliament, many of whom used to be political prisoners or vocal activists, were essentially muzzled by their leadership, which stipulates that “the MPs do not ask tough questions that make the government look bad” and that they do not speak to the media.

Maung Aung Myoe’s analysis of civil–military relations illustrates just how unrealistic the NLD’s 2015 election campaign promises are: peace, development, rule of law, and amendments to the 2008 constitution, which guarantees the sacrosanctity of the Myanmar military in the country’s politics. After all, the military continues to insist that the peace process must proceed within the constitutional framework, which is in effect federal in nature, and that there is no need for a federal union of armed forces, as desired by ethnic armed organisations.

“Our people’s perception, or rather, perceptions of democracy, varied, incoherent and inconsistent as they may be, impact on the transition that our country is undergoing today,” Daw Suu muses. It’s not just “democracy”; Myanmar’s peace process has been impeded by differing interpretations of key notions such as “federalism” and “inclusiveness” by different stakeholders. Despite that, Daw Suu is particularly upbeat about the results of the Union Peace Conferences held under her administration, particularly “a seven-step roadmap for peace and national reconciliation”. Detractors elsewhere have dismissed them as just more of the same, born of the “peace industry” that started under the previous government, where “ceasefire capitalism” in a protracted peace process benefits the military and elite stakeholders. Maung Aung Myoe notes that, whenever expedient, the NLD leadership has exploited provisions from the constitution, to the dismay of ethnic voters. For instance, the 2008 constitution enabled the NLD to appoint chief ministers from its own party in Shan and Rakhine states, where “the local assemblies are controlled by the non-NLD members”.

Perhaps nowhere is the transformation of Myanmar more evident than in its locus of power, Naypyidaw (officially “Nay Pyi Taw”). Even though it took time for the NLD to realise that Naypyidaw is part and parcel of the military’s transition package, the party — since Daw Suu and a number of her colleagues began working in the legislature, after the 2012 by-elections — has adapted quickly to Naypyidaw’s political culture. The capital, once scorned by the outside world as a “dictator’s paradise”, has in recent years been abuzz with activity, including the 2013 World Economic Forum and 2013 Southeast Asian Games. Nicholas Farrelly notes that even though Naypyidaw seeks to reflect the cultural diversity of Myanmar — barring the significant Muslim minority — its iconography, “especially at key political sites, is distinctly and directly tied” to the majority Bamar vision of national unity. Indeed, Naypyidaw is a political Las Vegas, built on the recurring motif of non-disintegration of the union, and on the table are some high-stakes gambles that will have profound impacts on the human and ecological wellbeing of Myanmar.

Those trying to make sense of Daw Suu’s attitude towards the Rohingya will not be disappointed. Kyaw Zeyar Win’s chapter sheds light on how the state securitisation narrative directed against the Myanmar Muslims over the past fifty years has consolidated the country’s mainstream view of the Rohingya as “enemy-other”, and how “Myanmar people have become securitizing actors themselves, envoys of the mainstream militarized securitization actors”, whose upward influence — in the open political environment of Myanmar in the age of social media — feeds elite thinking.

Some observers believe that although Daw Suu has been blatantly quiet on the plight of the Rohingya, her canonisation of her Muslim colleague U Ko Ni (an NLD lawyer assassinated by Myanmar nationalist elements in 2017) as a martyr for the country’s struggle for democracy indicates that her personal approach to the Myanmar Muslim issue may be more nuanced than the world will ever know. And yet her parallelism between the experience of the displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh and that of four million displaced people of Myanmar origin in Thailand sounds two-dimensional at best. So is her analogy between the repatriation programs for the two groups. Repatriation — a term that means return to native land — of the Rohingya is problematic exactly because both the state and the citizens of Myanmar continue to regard the Rohingya as aliens.

In Rakhine today there is not one but two armed organisations that are designated as terrorist groups by the Myanmar government. One is Rohingya — ARSA (Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army; formerly known as Harakah al-Yaqin, or “Faith Movement”) — and the other Rakhine (the Arakan Army). While both groups claim Rakhine as their native land, the state of Myanmar has historically regarded the littoral as a Lebensraum. Thrown into this tripartite conflict are global human rights, humanitarian aid and investment, as well as extreme Buddhist and Islamist interests, creating a delicate and complex situation of which only distant echoes of human suffering are likely to reverberate in the world media.

What can we learn from the Mon and Kachin, two of the major ethnic groups of Myanmar, whose visions of cultural identity and self-rule are incompatible with those of the majority Bamar-dominated military? Field research in several Mon townships by Cecile Medail reveals that self-identification of the Mon people as either ethnic nationals or Myanmar citizens varies among the group’s social strata. One expects the elite to be strongly ethno-nationalist, but the views among the Mon upper crust are not homogenous. While income is the greatest concern for the grassroots, strong Mon nationalist spirit is more prevalent in the conflict-affected communities. Naturally, the grassroots Mon people who live in predominantly Bamar areas tend to be less pronounced in their identity articulations. Medail recommends power-sharing and territorial autonomy “as core institutional arrangements that would enable and guarantee the effective implementation of measures promoting a sense of inclusiveness”.

What of Kachin? The political economist Giuseppe Gabusi argues that the military’s pervasive business interests, especially in the extractive industry on Kachin land, has convinced the Kachin Independence Organisation that “war would be the only way to halt the decline of the organisation’s grip on its territory”. Not only do revenues from the military-owned conglomerates Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings and the Myanmar Economic Corporation unaccountably go back to the military; numerous private-sector businesses are also owned by former military or military-related people and their cronies. Global Witness reports just how deep Myanmar military’s pockets are in Kachin; in 2014 alone the jade trade amounted to US$31 billion, almost half of the country’s gross domestic product.

Myanmar is a neoliberal state with one of the lowest formal taxation regimes in the world, and is also renowned as one of the most charitable nations. The World Bank considers Myanmar a lower-middle-income economy, but the country also has the lowest gross domestic product per capita in Southeast Asia. Sexual violence against children and women, drug problems, corruption, inflation, debt bondage, landlessness, environmental degradation and climate crises are daily realities for much of Myanmar. The country’s transformation is a textbook example of how a seasoned junta can plan a transition with military precision and secure its political and economic assets by playing cat and mouse with local and global opposition forces. There is no transitional justice in Myanmar.

![]()