I Feel No Peace: Rohingya Fleeing Over Seas and Rivers

Kaamil Ahmed

Hurst & Company: 2023

.

In December 2022, a boat was discovered adrift in the Andaman Sea off the coast of Thailand. A video posted on Twitter shows dozens of Rohingya men, women and children crouched listlessly on the ship’s deck while the crew of the Vietnamese vessel that rescued the boat circulated indifferently among them.

‘Rescue’ often contains hidden peril for the Rohingya, a majority-Muslim ethnic group with roots in the territory that now spans Myanmar and Bangladesh. In this case, the Vietnamese apparently delivered the survivors to the Myanmar navy, with whom they are unlikely to find safety. The same week the boat was discovered, the bodies of thirteen Rohingya teenagers were found on the side of a road on the outskirts of Yangon, in the wake of mass arrests of Rohingya people.

The Rohingya are not unique in a country where the majority Burmese, Buddhist ethno-religious power structure has singled out ethnic minority groups for treatment even more brutal than what they exert on the average resident. But for Kaamil Ahmed, who has been writing about the Rohingya for years, these events are part of a network of exploitation and neglect that implicates not only Myanmar’s government but also Bangladeshi, Malaysian and Thai officials. Also culpable are the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), shadowy entrepreneurs and even the humanitarian workers and journalists supposedly ameliorating and documenting the suffering.

Ahmed’s beautifully written and utterly demoralising book weaves together the stories of Rohingya people who are not just buffeted by tragedy but are also agents in a struggle for justice. His quasi-ethnographic immersion in Rohingya communities allows him to explain decisions that may seem foolish to those in positions of privilege: for instance, boarding an unseaworthy vessel with hundreds of other desperate people; remitting your life savings to a human trafficker who has kidnapped your loved one; or repatriating to a country you fled. Ahmed shows that these are not ‘choices’, but attempts to find the least dangerous option when information is scarce and safety unavailable.

I Feel No Peace is the opposite of the superficial glosses from reporters who dip into refugee camps for a few days. His insights do not stem from one location, but from the life stories of his informants. As the timelines of these people’s lives are laid against one another, an understanding accrues of key moments in this extended crisis: 1978, when General Ne Win’s Operation Nagamin caused hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh; 1983, when Myanmar’s citizenship law was revised to exclude groups like the Rohingya; 1994, when the UNHCR cut refugees’ food rations, resulting in the death of ten thousand and the refoulement of many more; and the violence that presaged the Myanmar military’s torching of the Rohingya village of Tula Toli on 30 August 2017.

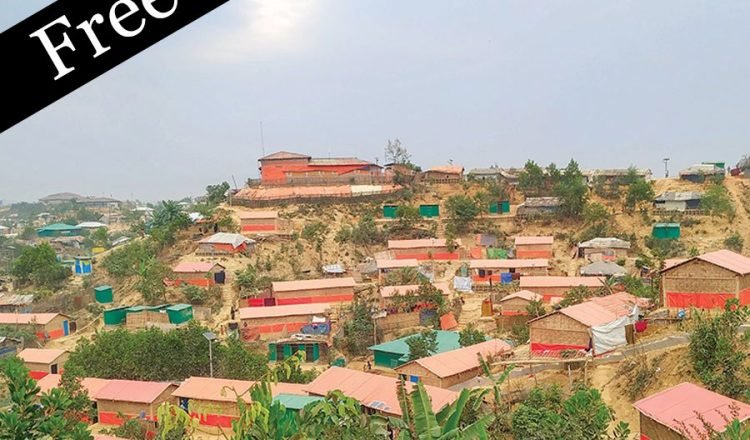

This village is where Ahmed’s book begins. He tells the story of Momtaz, who describes being raped by soldiers, seeing her children murdered and escaping badly burned with her surviving six-year-old daughter to Kutupalong, the largest refugee camp in the world. Physically scarred and emotionally traumatised, she remarries for security but is abandoned by her husband. She sells her rations to support herself, her daughter and her new baby, becoming enmeshed in the twisted economy of aid.

Other stories reveal the transnational network of exploitation. Childhood friends Zia and Nobi are raised in Nayapara, a little-known refugee camp established in Bangladesh in the early 1990s. After perfecting his English and seeking every educational opportunity, Nobi is chosen for resettlement in the UK. But the programme is cancelled at the last minute, and he’s left indebted for the supplies he’d bought for the journey. Meanwhile, Zia is trafficked to a camp in Thailand where Rohingya people are imprisoned and sold. He’s briefly hopeful when Thai authorities raid the camp, but the police re-traffick him to Malaysia. Zia becomes a community spokesman and even meets Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, but is targeted when Malaysia scapegoats the Rohingya for spreading Covid-19. The book ends with Zia and Nobi waiting for news about a fire that has destroyed their section of Nayapara; Nobi is distraught to learn that the educational certificates he had collected for decades have gone up in flames.

For the Rohingya, the world is one in which paper holds unlikely weight. In this passage, we learn why: “Inside a set of thin plastic wrappers, the type that seal at the top and usually contain lungis or shirts sold from market stalls, Mustak Ahmed archives his dearest possessions—the precious family documents collected by his father and then himself.” These should have qualified the elderly Mustak, who lives in Myanmar’s Rakhine State, for a kind of second-class citizenship, which is all the Rohingya are eligible for after an exclusionary 1983 law. Despite these papers, which prove that his ancestors lived in the nation’s territory before British colonisation in 1824, Mustak has been waiting for a response from the Immigration Department since 1989.

This is the paradox of being Rohingya. The Myanmar government’s simultaneous insistence that the Rohingya don’t exist, and that they must be obsessively controlled, has led to perverse outcomes: some Rohingya refugees in the 1970s ripped up their Myanmar identity documents in hopes they couldn’t then be forced to return, rendering themselves permanently stateless.

Gaslit, misled and abused, Ahmed’s informants refuse to give up. They organise online, “the one place where Rohingya can live in a shared space”. When Fatima is abandoned and left indebted by her husband, she becomes a drug mule, ferrying yaba to support her two children. Ahmed’s descriptions help readers see that what seems like folly may be a courageous swipe at survival. But he doesn’t romanticise the Rohingya as angelic victims. He documents the crime networks that weave in and out of the refugee camps around Cox’s Bazar—a city in southeastern Bangladesh that received hundreds of thousands of fleeing Rohingya—all the while eroding readers’ moral high ground with an unspoken question: What would you do to feed your family?

Ahmed’s book includes anecdotes of bad journalism. In a frenzy to find information about the Rohingya insurgent group known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) after clashes in 2017, journalists misunderstood how loosely organised ARSA was. “Few [Rohingya] knew exactly what they were or how they were run,” Ahmed explains. International journalists, desperate for members of ARSA to interview, instead found Nobi, who tried to explain why some Rohingya might turn to violence. A few days later, he saw himself on an American TV channel, presented as a member of ARSA.

Nor does Ahmed conceal his disdain towards “the world’s aid workers, who rushed in and stayed in luxury hotels”. Indeed, uninformed internationals are minor villains in this story. Ahmed harks back to UN reports from the 1990s that portrayed the Rohingya as partially responsible for state violence against them, and dwells on the UN’s decision to cut rations to Bangladeshi camps and pressure refugees to repatriate despite little guarantee of their safety in Myanmar. Senior UN officials damn themselves with their jaw-dropping pronouncements: “The Rohingyas are a primitive people. At the end of the day, they will go where they are told to go.”

All the forces Ahmed describes converge to make life extremely dangerous for the Rohingya. So it’s fitting to end with Mohibullah, a civil society advocate who finds relative success drawing attention to his people’s plight, even travelling to the White House to plead his case. When he told US President Donald Trump he wanted to return home and was in a refugee camp, Trump asked, “Where is that exactly?” In 2021, Mohibullah was murdered in his organisation’s office, presumably by ARSA.

Throughout his book, Ahmed draws a contrast between the dismal fate of the Rohingya and the career opportunities for those with the power to represent them to the world: “Their lives have become known as a crisis, photographed and written about, made the subject of films—all of which have won awards for their creators.” This book should win awards too. But I doubt Ahmed will forget his friends.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Issue 30, Kaamil Ahmed, Myanmar, Rohingya, Rosalie Metro