Tales of an Eastern Port: The Singapore Novellas of Joseph Conrad

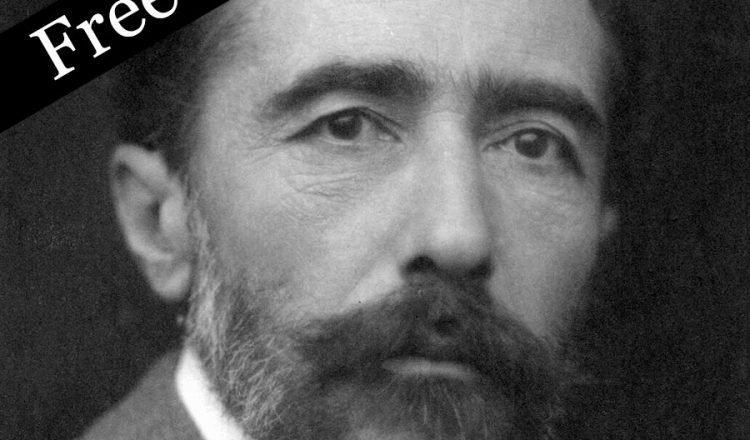

Joseph Conrad

NUS Press: 2023

.

Tales of an Eastern Port: The Singapore Novellas of Joseph Conrad is a collection of two Conrad novellas: The End of the Tether (1902) and The Shadow-Line: A Confession (1917), as well as an insightful essay by Kevin Riordan, an assistant professor in the humanities faculty of Nanyang Technological University, on Conrad’s Southeast Asian stories and the ever-changing place he holds in post-independence Singapore. In the two stories, journeys depart from or hope to return to “an eastern port” (Singapore) but instead they both disappear into the obscurities of the seas.

English was Joseph Conrad’s third language, learnt when he became a sailor in his twenties. Polish and French were his first and second languages and yet it was as an author in the English language that he became one of the most famous writers of his age. His near neighbours and good friends in southern England were other titans of the literary scene: Arthur Conan Doyle, HG Wells and Rudyard Kipling. After his death in 1924 his reputation fell away until the literary critic FR Leavis’s influential book The Great Tradition (1948) asserted emphatically that “the greatest novelists in the English language are Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James and Joseph Conrad” and that Conrad in particular was “among the very greatest novelists in the language—or any language”.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that Leavis’s book was published in the same year as George Orwell’s 1984, because Leavis demanded moral seriousness and moral intensity. He dismissed Charles Dickens as an entertainer whose work was unserious (apart from Hard Times). Jane Austen’s world was tiny compared to Conrad’s, who worked on ships on every ocean, but for Leavis she described her world intensely, completely and with a moral standpoint. Still, in his stories, Conrad’s world was not so very large. The setting of the vastness of the sea devolved to the heightened domestic strife on a ship. One end of the tether might be the global, imperial trading network centred on London (or its Asian stand-in, Singapore) but at Conrad’s end there are failing ships, failing eyesight and failing businesses, all pressuring the mercury on floating moral codes like an unforeseen typhoon.

In The End of the Tether, a once-successful ship’s captain is forced out of retirement because his savings have been wiped out by a banking crash. He wants to leave something for his estranged daughter who lives in Australia, so he takes command of a steamboat in Southeast Asia. The boat is a disaster; the boiler should have been replaced, a crew member is a drunkard and the owner is a hopeless gambler. But Whalley, our captain, is determined to succeed for his daughter and because his sense of morality demands that it is the right thing to do. Unfortunately, his eyesight is failing, which is covered up by the boat’s first mate, “an elderly, alert, little Malay, with a very dark skin, who murmured the order to the helmsman”.

Whalley and this Malay man are the first two characters to be introduced to us. The Malay man clearly has trusted authority and competency as a sailor, and this portrayal might have come as a shock to Conrad’s contemporary English readers—as would the fact that the narrator’s employer in The Shadow-Line is an “excellent” Singapore Arab—but it is intriguing for today’s Asian reader because he was a witness to, worked with and for late-nineteenth-century Southeast Asians. Conrad was not entirely alone in putting words into the mouths of non-Europeans, but he was rare. Kipling did it all the time, as did lesser writers and actual colonial administrators like Sir Frank Swettenham and Hugh Clifford. These Englishmen were heavily invested in the rightness of the British Empire. Conrad was not. In The End of the Tether, the boat glides slowly past a market. The market people could have been portrayed as grotesque, indolent or, worse still, noble (I have read all in nineteenth-century memoirs), but instead they are seen as simply so very casual and comfortable in their world that the observer (Conrad) tacitly becomes the ‘other’, intruding on an unhappy boat that barely functions.

This must be where we see Conrad the Pole. He might have retired to England from the sea and written in English but he was always from Poland, a country that in his lifetime did not even exist. The once-mighty Poland had been completely swallowed in three giant Partitions by Prussia, Austria and Russia in the eighteenth century. Conrad’s part of Poland lay inside the Russian Empire (his hometown suffered damage in Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine) and his own father was a hunted poet to Polish patriotism. Long before sailing to Asian and African ports under the flags of the British, French, Dutch, Portuguese or Belgian empires, Conrad experienced a childhood as a colonial subject of the Russian and Austrian empires. Like Ireland, another European country that did not yet exist, Poland exported people, including Conrad, who spent eighteen years at sea and much time in Singapore where, Riordan says, his nickname was “Polish Joe”.

It is probably because Conrad was Polish that I admire him so much, but it is also perhaps why I admire him more in theory than in practice. As a student of nineteenth-century European imperialism in Southeast Asia and beyond, I relish Conrad’s Polish audacity in portraying Asian as well as European characters. He was there, working alongside all manner of people, he was not British. We must take his observations seriously, even if, as Riordan points out, he was “a dependably unreliable narrator”. Because he was from a family of poets and English was his third language, there is an elliptical density to his prose that fills in spaces, landscapes, characters and themes in a manner that exposes how too often the native speaker deals tritely in their own language. And yet, sometimes I wonder, is he translating from Polish into English? I find his language to be quite difficult, even heavy-going. It took me months to finish Heart of Darkness and it’s the thinnest book I own. It’s wondrous but, jeez, it’s hard work. My favourite author is Charles Dickens (Leavis and his “moral intensity” be damned). His work flows, like the River Thames, whereas for me (and it is my failing) Conrad can be turgid, like the sea. Although, once you have experienced Conrad’s saltwater, the taste will never ever leave you.

Smuga Cienia (1976) is the great Polish film director Andrzej Wadja’s adaptation of The Shadow-Line, shot on the Black Sea and in Burma when Poland was still inside the Soviet bloc. It is, to my mind, the best film version of a Conrad novel (after Apocalypse Now). As a Pole, Wadja was not interested in giving the English characters redemption or a backstory; they are entirely shorn of any hope for imperial triumphalism. Instead he latched on to the images that Conrad alone has given us: the sweatiness, illness, failures, and moral as well as financial bankruptcies inside the empire, which, as Marlowe says in Heart of Darkness, “is not a pretty thing when you look at it too much”. These are precisely the images that sing in Conrad’s world, even if his actual views on imperialism are not altogether apparent. He offers a perhaps unique, untrammelled glimpse into the desperation of the European and occasionally the Asian world of the late nineteenth century.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Issue 34, Joseph Conrad, Kam Raslan, Singapore