Splashed across numerous international publications last November was an image of a young man in an orange jacket, a blue hoodie and a black face mask, surrounded by a crowd of people on a city street, staring fixedly at the camera. Holding up a white piece of paper with his right hand, his left points determinedly at… us. This direct address seems to demand something of the viewer, but as his sign is blank, his message remains elusive.

The hundreds of people who surround him also hold white pieces of paper, suggestive of a shared purpose. Static documentary evidence of a crowd could plausibly be read as a rally, a protest, a celebration. The choice of white, however, and its association with mourning in China, helps characterise the event as a vigil. And that is exactly what it was, or at least how it started.

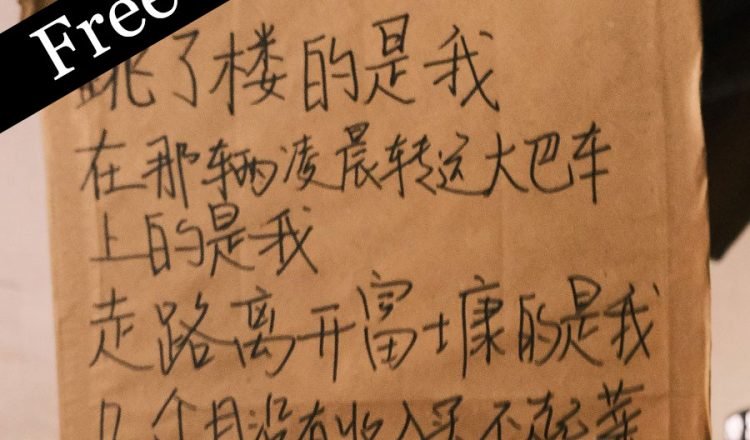

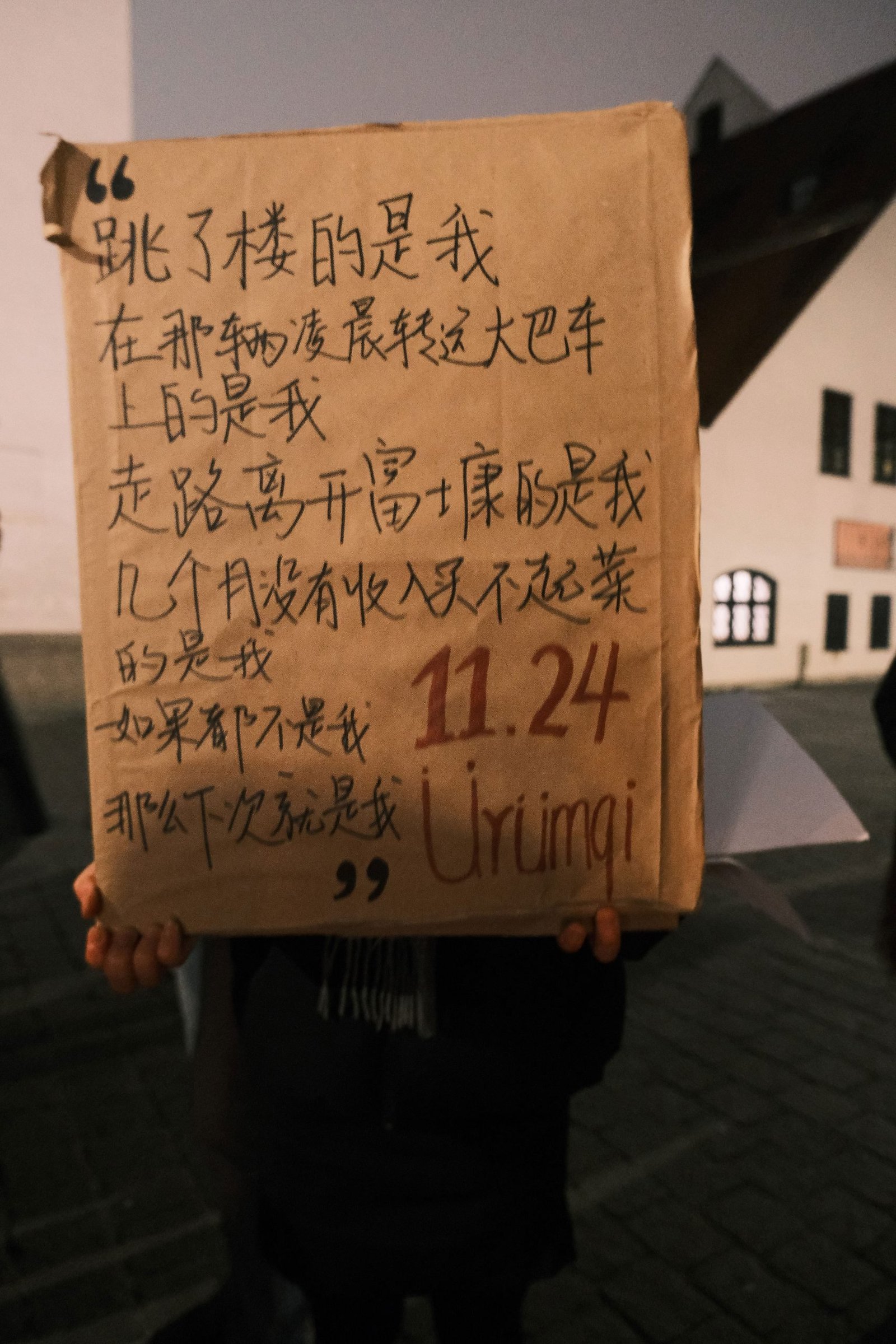

These public gatherings began as a way to remember the ten lives lost in Xinjiang province on 24 November 2022, after a fire broke out in an apartment building where residents struggled to escape due to movement-control obstacles introduced to prevent the spread of Covid-19. While the gatherings—like the one in Shanghai on Wulumuqi Road (named after Ürümqi in Xinjiang)—started as a way for a grieving public to mourn, they quickly transitioned to large-scale protests. Many directly called for an end to President Xi Jinping’s stringent zero-Covid policy, while others rejected his repressive measures and, in some cases, his regime.

Since participating in a protest in China puts one’s physical safety in jeopardy, using a blank sign serves as a form of plausible deniability. It is also consistent with the complex reality of memory and historical events in China. In Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China, Margaret Hillenbrand writes, “Public secrecy is self-defensive, because those who break the secrecy in China might face grave sanction.” Contrary to popular assumptions, the threat of penalty doesn’t prevent protests in China; in fact, they occur on a nearly daily basis.

The man in the hoodie was participating in what has since been termed the A4 Revolution, or ‘blank paper’ (白纸) movement. These protests took place across different cities in China, carrying a unified message. People posted a white square, the digital analogue to protesting in person, to their WeChat timelines en masse. The protests displayed solidarity across ethnic groups and borders.

The A4 Revolution unfolded after the October 2022 Sitong Bridge incident, where a protester hung a massive banner over a major Beijing highway criticising the zero-Covid policy and demanding freedom, elections and “to be treated as citizens, not slaves”. This catalysing event took place immediately before the twentieth CCP National Congress, where Xi would secure a third term in power—a departure from Chinese political procedure which previously capped terms at two. Once images of the banner circulated online, the Chinese diaspora responded with solidarity protests and social media campaigns. Printouts of the Sitong Bridge demands were spotted on university campuses in dozens of countries, Twitter and Instagram were inundated with photos of the demands and it seemed that despite the Great Firewall and thousands of miles of distance, everyone was talking about the same thing. The CCP considers mass focus of this nature to be one of its greatest threats.

When you suddenly have no autonomy to move, make plans or participate in the economy, you have a lot of time to think. Losing the freedom to go untested or unmasked for more than a couple of days might have made other missing freedoms more conspicuous. The A4 Revolution capitalised on the energy of opposition to China’s stringent zero-Covid restrictions. This strategy, while far from impervious to China’s censorship regime, generated a movement marked by unexpected unity. From the perspective of the Chinese government, the A4 Revolution’s nature as transcending disparate social groups, leaderless yet indirectly coordinated, and in clear conversation with other protests that took place in the weeks and months leading up to it, all made it precariously extensive. Unlike local protests, where small groups lob contained grievances at factory bosses or regional officials, the A4 Revolution’s use of white paper provided a space for both protester and audience to fill in the blank, allowing some to choose total opposition.

China’s Great Firewall and its unparalleled degree of authority over public speech, both online and offline, create two groups of people: those who ‘know’ and those who don’t. The white piece of paper, as a visual language of resistance, tears at this binary. While this protest symbol is consequential to those who have studied China’s political and social developments throughout the zero-Covid era and Xi’s last decade in power, it likely held no immediate significance for other onlookers who might not have been paying attention to circumstances beyond their own. But anyone who lived through zero-Covid could instinctively recognise the anger, frustration and mourning carried by the blankness. It signalled both a recognition of the authorities’ failure and a demand for deeper change.

China’s social media platforms no longer display images related to the A4 Revolution. But during the weekend after 24 November, many human censors were not working, making the white square harder to identify as worthy of censorship. Also, the official narrative on the Xinjiang fire and possible changes to the zero-Covid policy were still being crafted, resulting in a further delay in censorship. The reaction had to be delivered from the top, and Xi was presumably still making up his mind about how and whether to change China’s Covid policy.

In early December, the Chinese government suddenly started easing its zero-Covid restrictions, a reversal whose significance is hard to understate given Xi’s personal ownership of the policy. Amid the rampant and deadly spread of Covid throughout the country that unfolded as a result, the government began rounding up protesters. Easy targets for police and security services include feminists, members of the LGBTQ+ community and people who have lived abroad. From the state’s perspective, such individuals are more likely to retain a reason to protest even after the end of pandemic restrictions. They were subjected to detention, questioning and sentencing. Detainees could face ten years in prison for holding up blank sheets of paper.

The CCP’s brand of authoritarian governance, which it terms “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, relies on a state-led and socially absorbed practice of forgetting. The process of erasing traumatic events from both the personal and national psyche plays out collaboratively. The CCP’s seventy-four years leading the country has created ample opportunity for intergenerational training in the art of forgetting as survival. Blank paper as a protest symbol both upholds and subverts this notion, speaking directly to the silence and breaking it.

The white paper’s emptiness provides inherent cover, even though its stealthiness erodes every time it is used. It may no longer obfuscate the classification of protest or outcry. But, as the writer and particle physicist Yangyang Cheng argued—this method cannot be erased: “The absence is a mirror held up against state terror, a vessel for divergent grievances, and a path to infinite possibilitie

In the Chinese context, protesters’ use of the blank paper is a nod to the implicit understanding between people and party that everyone should intuitively know what they are supposed to forget. The protesters in the A4 Revolution assumed the risks of public intervention, even though they had no way of knowing who would end up listening. Xi’s full-throated and sudden reversal of a policy that all Chinese citizens had sacrificed so much to comply with for three years broke whatever degree of trust they may have had with the government.

Protesters wanted the zero-Covid policy to end, but they didn’t want the system protecting them from the virus to vanish without a replacement plan. Many elderly people remained unvaccinated at the time the policy was reversed, leaving patients’ families feeling as if the government—which had no problem carrying out massive intrusions into citizens’ daily lives throughout the zero-Covid era—could not be bothered to take smart steps to protect the country’s most vulnerable.

That betrayal, coming in the form of an absolute about-face, has perpetuated resignatory trends in China today like ‘involution’ (内卷), ‘lying flat’ (躺平) and ‘runology’ (润学). These phrases, popularised on Chinese social media platforms, convey the sensation of participating in a cutthroat society with limited prospects for payoff; the government’s contradictory Covid policies were case in point to many that their leaders are fundamentally not looking out for the people’s well-being.

If these concepts are emotionally and logically absorbed by a critical mass, they stand to change the risk calculus of participating in protests. ‘What’s the point of speaking out?’ becomes as valid as ‘what’s the point of staying silent?’

At one event in New York, Chinese protesters—many wearing masks, hats and sunglasses out of fear that they would be photographed, recognised and punished upon their return to China or earlier—rallied outside the PRC consulate. Uyghur activists talked about how zero-Covid fit a pattern of repression in Xinjiang. Speeches were delivered in Mandarin, English and Uyghur. Some people’s signs focused on the individuals killed in the Ürümqi fire; others identified themselves as Tiananmen alumni; still others held banners demanding that Xi step down.

These protests were striking in their range and intersectionality. Yet, all their demands and dimensions can be traced to the blank white square and the individualised canvas for dissent it created.

![]()

- Tags: China, Free to read, Hannah Sage Kay, Issue 32, Johanna Costigan