z

On 28 October 1943 Clive wrote that he was “very busy with my crew, getting my tank absolutely tip-top.” They were preparing for Burma. The tank Clive was to command in B Squadron of the 25th Dragoons was an M3 Lee, made in America. Formidable Lees loomed more than three metres tall with a sloped front of riveted thick steel plate. The intimidating barrel of a 75 millimetre gun protruded off-centre and a 37 millimetre gun barrel jutted from the oval turret.

Lee tanks had crews of seven stuffed like mollusks into interior compartments amid ammunition racks and other equipment. Noise from the whirring, grinding engine and firing guns was inescapable. As John Leyin commented in his memoir of the 25th Dragoons, “being battened down in the tank in the tropical heat, with the sweat running down my bare torso into an already sweat sodden waistband of my shorts, and with the smell of expended cordite pervading the turret, was definitely not a plus.” When their armour failed against any kind of superior firepower, World War II tanks provided especially terrible ways to die: penetration by fireballs, chemical burns, massive holes blown through head/torso/limbs, swarms of searing, ricocheting metal fragments.

Where they were headed, the Lees of the 25th Dragoons would be opposing a Japanese force without tanks. So this was without the terror of going machine to machine against German tank technology, as was the case in North Africa or Europe. Tigers and panthers were actual animals in Burma, not notorious Nazi tanks. But the Japanese did have plenty of anti-tank guns which were dangerous at close range, plus less effective attempts at traps and mines. There would even be an incident much later in the Burma campaign when a Japanese artillery officer somehow managed to climb inside a British 3rd Carabiners tank and kill the commander and a gunner with his sword.

As a tank commander, Clive would share his turret with the gunner and loader for the 37 millimetre while the hull below held driver, radio operator, 75 millimetre gunner and loader. He admired them all: “Fortunately in the modern arm of the Army—tanks—one is helped to keep sane by continual contact with machinery, and still more by contact with the real technicians, the drivers, gunners and operators. These people have no romantic ideas about things, they don’t confuse tanks with horses, they don’t mix up a shouted command with the technical job of making the tank go.”

Tank commanders must supervise their crew while navigating, ordering and directing fire as well as coordinating tactics with other tanks and higher command. With all the noise, intercoms were used for communication within a tank and radio connections, known as “the net”, linked with other tanks in a troop or squadron. A soldier in a story by Welsh writer Alun Lewis (who trained on tanks in World War II India) speaks of “the big 75 mm. gun and the voices of your friends in your headsets coming over the air.” Ideally, a tank crew operated with deep mutual respect and crew members often risked their own deaths to drag crewmates out of hit tanks.

In his book, Brothers in Arms, about a Black American tank battalion in World War II Europe, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar observed that a tank commander was selected “based on character evaluations” indicating “steadfast concern for others and the loyalty he earned in return.” Clive took this role seriously.

In a January 1944 letter he told Noreen, “in the main I worry about whether I shall command my tank as a Communist ought.” For Clive being a good Communist meant being fair-minded, egalitarian, brave.

The commander’s vision port in the turret of a Lee was just a narrow horizontal slot. Field of vision was important for commanders, so unless under direct fire they often stood with their upper body exposed to armpit level out of the hatch, scanning with binoculars. Sometimes they would dismount for a recon. Either situation could be dangerous. In his memoir, Tank Action, David Render recalled being shouted at to get in the tank on his first day as a nineteen-year-old tank commander in Normandy, because “we didn’t bring all these bloody tanks over here to have no one left to crew them.” Tank commander Keith Douglas had been killed by a piece of German mortar shell to the head when he was outside of his tank the day before.

Often considered World War II’s greatest poet, Keith Douglas’s North Africa poems described “dead tanks, gun barrels split like celery” and a German gunner who “hit my tank with one / like the entry of a demon.” I read his North Africa tank warfare memoir From Alamein to Zem Zem. Illustrated with his drawings, it made me like him very much: near-sighted, insubordinate, an enthusiastic looter of Italian cherries in jars and German chocolate. But then I ran into his casual racism, his Nazi-level anti-Semitism. Had they met, Clive would have had to ask him “What are you even fighting for?”

Clive was a person of action, but who wasn’t in those days? Lists of the poets who fought fascism in World War II contain many men in aeroplanes, some men on ships, women in corridors of Intelligence or hospitals. I looked for poets in a land war like Clive’s. British poet John Jarmain was, like Douglas, an officer in North Africa (anti-tank battalion) then killed in France. Poet Randall Swingler was a comrade of Clive’s in the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) who served with a British signals unit in North Africa and Italy, was awarded the Military Medal for bravery, and put under surveillance after the war for his politics.

Alun Lewis, who seems to have been in constant personal turmoil, became a 2nd Lieutenant in the South Wales Borderers. Burma seems like his codeword for death. “He’d always known he’d die if he caught up with it in Burma” in his story ‘The Earth is a Syllable’. The poem ‘Burma Casualty’: “His regiment too butchered to reform.” Editor Keidrych Rhys would call this Lewis’s “terrible premonition-impetus”.

When Lewis arrived in Arakan, coastal Burma, he was an Intelligence Officer stationed at the rear, but insisted on visiting a frontline base on 4 March 1944. The next morning, he apparently shot himself in the head with his pistol. In Arakan, as in other war zones, it could be harder for a twenty-eight-year-old lieutenant to avoid death than to meet it. So why did Lewis have the compulsion to write the end of his own story then? And there? Perhaps the equation ‘Burma = Death’ was all he needed.

The American poet George Oppen had much in common with Clive. From a wealthy family, Oppen decided to “change class” with his poet/artist wife Mary. In the 1920s they roamed the country like Bonnie and Clyde, but packing a poetry anthology instead of guns. Joining the Communist Party in the 1930s, they decided, in Mary’s words, “Let’s work with the unemployed and leave our other interest in the arts for a later time.” With their daughter they formed a little Red family.

Oppen could have avoided the draft, but to fight fascism he served as an Army truck driver and gunner in Europe. At age thirty-six (the same as Clive at the time of his death) he was severely wounded in a German forest by fragments of a shell, probably fired by a Tiger tank. Like shrapnel working its way out, war trauma would always emerge in his poems. “I cannot even now / Altogether disengage myself / From those men / With whom I stood in emplacements, in mess tents, / In hospitals and sheds and hid in the gullies / Of blasted roads in a ruined country,” surfaces in his great PTSD Mad Men New York epic ‘Of Being Numerous’.

“Where did all the rocks come from? / And the smell of explosives / Iron standing in mud” appears in ‘Survival: Infantry’ published in 1962. Oppen’s shredded flak jacket did not augur survival, but he would live to experience ‘Howl’, the Altamont rock festival and an island in Maine, eventually dying not of Nazi ammunition but Alzheimer’s. In photos of his lined face I see the poet Clive might have become.

Other poets who fought in the US Army included Richard Wilbur, a Staff Sergeant of the “hard luck” 36th Infantry in Europe (he wrote a poem to lick the blood off of: ‘On the Eyes of an SS Officer’.) Lucien Stryk was well named for an Army Forward Observer in the Pacific. More infantry veterans, scarred survivors who might write about the war but not talk about it much: Kenneth Koch (Army rifleman, Philippines), Anthony Hecht (Army rifleman, Europe), Louis Simpson (Army infantryman, Europe), James Emanuel (Army Infantry sergeant, Philippines and New Guinea.)

Surrealist poet Rene Char led French Resistance units in the Alps and Provence, earning the Croix de Guerre. Vladislav Zanadvorov and Mirza Gelovani were promising young Soviet poets who died in combat against Nazi Germany. Polish poet Anna Świrszczyńska was a Resistance military nurse during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. She survived capture and later wrote a series of scaldingly honest war poems collected in Building the Barricade. As translated by Piotr Florczyk: “When the world was dying, / I was but two hands, handing / the wounded a bedpan.”

A path from Spain to China runs through poems of Auden. After his visit to wartime Spain, Auden set off with writer Christopher Isherwood on trains and boats to the Sino-Japanese War, another horrible precursor to World War II. One of my favourite books resulted: Journey to a War, Isherwood’s travelogue with sonnets by Auden, who I’ve adored since my parents brought me to see him read at Princeton in 1967. Other people who loved Auden included Chinese poets Mu Dan and Du Yunxie, both of whom would volunteer in the Chinese Expeditionary Force in World War II Burma. As students they had read Auden’s China book and his ‘Spain 1937’ and were inspired to write poems and fight Fascism, in this case the militarised Japanese regime.

Mu Dan, who served as an English language interpreter between Chinese and British armies wrote a strange rapturous elegy, ‘Forest Apparition: Honouring the Bones on the Hukawng River (森林之魅 — 祭胡康河上的白骨)’ based on his 1942 monsoon ordeal: in retreat after battling Japanese forces, one of the few survivors, straggling alone on foot, ill, starving, across northern Burma to India. Published in 1945 and later translated by Wang Hongyin, the poem resounds with insects, gibbons and the voice of the forest itself. Ending in oblivion: “No one knows that history once passed through here, / And left your soul now growing in the trees.”

In the Box

On 5 December 1943, Clive wrote a poem he called ‘Orders for Landing’. It concludes with the lines “Like words we live, self-lost in history. / We sink like waves into the endless end.”

Clive knew he would be participating in a historic struggle against fascism in Burma, as he had in Spain. While he vehemently rejected British colonial rule as anything worth fighting for, he believed in a multi-front war against Hitler’s Germany and the other fascist regimes, which included the Imperial Japanese Army.

An American troopship brought Clive and his Lee tank across the Bay of Bengal en route to Arakan. Stretching down the west coast of Burma with an isolating ridge of mountains, Arakan was an independent sea trade power for many centuries. Conquered by Burmese invaders in 1784 and under British colonial rule since the late 19th Century, Arakan is now Rakhine State of Myanmar (Burma), now known to the world as the site of the Myanmar military’s genocidal attacks on the Rohingya people, intensifying a pattern of oppression during decades of military rule. That military and its ruthless tactics date back to Japanese fascist training of Burmese leaders during World War II.

The Japanese invasion of Burma in late 1941 spurred a massive retreat to India by British administrators, soldiers and hundreds of thousands of civilians, including Indian workers. 1942–43 British/Indian attempts to retake Burma through Arakan were repelled by Japanese soldiers who gained a reputation as fearsome jungle fighters. War artist Anthony Gross witnessed the First Arakan Campaign, painting Indian troops in bamboo groves and British corpses sprawled on the sand at Donbaik beach.

The Second Arakan Campaign was in the works by late 1943, including moving a secret weapon there via the coast of Chittagong, in what is now Bangladesh. That weapon was the Lee tanks of the 25th Dragoons. At their holiday celebration in Chittagong, Clive recited Wordsworth’s ‘Westminster Bridge’ and was asked to give a speech. “So I told them that in the hard days to come if they stuck together in the same spirit in which they had got together for Xmas we would do all right.”

Clive was promoted to Troop Sergeant which meant that on manoeuvres he would be in charge of a troop of three tanks. On 22 January he wrote, “Zero hour is getting nearer and although I am by no means a superman, I cannot help feeling glad I may do just a little bit towards beating fascism,” adding, “The lads have just cooked some really superb raisin fritters.” By 26 January he was at the front and wrote of Japanese planes overhead, Japanese entrenchments in the hills. He contrasted the British troops’ well-armed situation with his memories of undersupplied Spain.

One last letter from Clive has been published, dated 4 February. The 25th Dragoons had fought well in their first battle. Clive focused on details of camp life, the “bloody unappetizing” food. He mentioned a large snake and a tiny moth. He closed with a recently written sonnet with these final lines:

I felt perhaps I’d understood at last

By close observance of all that nature showed

“When life has gone, then where does death begin?

Late in the day on 4 February, B Squadron (including Clive) of the 25th Dragoons was urgently moving east on the Ngakyedauk Pass. For what happened next, in place of Clive’s words there are other B Squadron accounts, notably memoirs published long after the war by Tom Grounds and John Leyin. Descending from the Ngakyedauk Pass, Grounds recalled, “the jungle looked menacing and eerie. We seemed to have left the real world behind and moved into a dimension where anything might happen.”

B and C Squadrons were responding to a surprise Japanese offensive preempting the planned British/Indian campaign. Major General Tokutaro Sakurai of the Imperial Japanese Army moved to secure roads and tunnels in northern Arakan as a route to invading India. In a stunning assault on 6 February, Japanese infantry overtook the 7th Indian Division Headquarters on the east side of the Pass, killing many. HQ survivors made their way to a nearby Administrative Area which became the Admin (for Administrative) Box (a defensive position). Its escape or rescue route, the Ngakyedauk Pass, was cut off the next day.

The roughly rectangular Admin Box was only about 1,400 metres by 700 metres, mostly flat rice fields ill-suited for defence, in sight of surrounding Japanese-held hills. Clive and others had noticed civilians trying to live normally in Arakan as the war circled around them. But when the Japanese pushed west, the villages around the Admin Box were hastily abandoned by Rohingyas (who were particularly helpful to the British) and other ethnic groups.

Jammed into the Admin Box were multi-ethnic combat troops from units that would include the West Yorkshire Regiment, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, Gurkha Rifles, Bombay Grenadiers, Punjab Regiment and Royal Artillery units and B plus C Squadrons of the 25th Dragoons, as well as thousands of non-combatant personnel like medics, clerks and muleteers.

Ammunition was stored around a small hill at the centre of the Box. The 25th Dragoons’ tanks were based near Ammunition Hill and other areas were designated for trucks and pack mules. Medical facilities had to be moved to a safer location after the field hospital near the Box perimeter was overrun on 7 February with a horrific massacre of patients and medical staff, which particularly made the Admin Box defenders loathe their Japanese enemies.

For the Allies fighting Japan, Burma was needed as a supply line connection between British-controlled India and US-supported China. Japanese pushback of the nascent British/Indian incursion into Arakan was unacceptable. British command ordered the defenders of the Admin Box to hold their position at all cost, promising air resupply and fighter planes to drive away Japanese bombers. On 11 February the Box defenders began receiving parachuted rations, ammunition, fuel for tanks, and even mail. Perhaps letters from “sweet comrade” Noreen reached Clive.

Japanese attacks on the Admin Box were continuous, probing and intense. Every night screaming Japanese raiders would try to get past the defenders’ trenches at unpredictable points in the perimeter. Casualties were high on both sides from artillery, grenades, bayonets. The defensive lines held but sleep deprivation in the Box was severe. Tom Grounds recalled, “You watched the edge of this jungle for movement and, of course, saw it—but it was just the night breeze stirring the tall plumed grass and the bushes—or was it a figure?” Japanese air raids added to the chaos. Ammunition Hill was repeatedly bombarded, setting off the ordnance like fireworks.

Trapped in the Admin Box, the Lee tanks of B and C Squadrons proved their worth, big guns blasting at Japanese positions in the surrounding hills. An innovative strategy was devised in which tanks would first fire high explosive rounds at the enemy emplacements, followed by armour piercing rounds which arced above advancing West Yorkshire or Gurkha infantry, allowing them to get close enough to charge. This bunker busting technique proved highly effective against all but the most tunnelled-in Japanese gun crews.

Although well-armoured, the tanks were not impervious to Japanese ammunition. On 11 February, a shell hitting one of B Squadron’s Lees set the interior ablaze, killing the 75 millimetre gunner and loader; the driver and radio operator would also die of their burns. Tom Grounds wrote, “we faced the grim task of getting the dead men out and also all the live ammunition, much of which was singed and highly explosive. I shall not forget the burned and wizened, half-crushed head of the loader.”

Grounds wrote that by 19 February “the Box was becoming a shambles. High-explosives had flayed the leaves from the trees and pulverised the undergrowth; the one-time padi [rice fields] of the villagers had become a baked mud arena churned up by the tracks and wheels and surrounded by gaunt tree stumps… It was becoming a mass of flies.” Shelled, bombed, strafed and charged into relentlessly all night and day, the crowded Box reeked horribly of unburied corpses: Japanese, Indian, British, Gurkha and mules.

The 25th Dragoons were ragged, unshaven and unwashed. Malaria and dysentery were common, minimal treatment available. Even with the airdrops, rations were basic. But office and support staff fought resolutely alongside the defending infantry and tank units. Meanwhile the Japanese troops showed extraordinary courage, refusing to withdraw even as their commanders’ plans to capture supplies failed and starvation ravaged their ranks.

B and C Squadrons developed a routine of revving up their tanks around dawn to test the possibilities of breaking through the Japanese lines. Heading east, the dirt road featured a curve nicknamed Tattenham Corner (after a bend in a British horse racing track) which was inevitably shelled from particularly well-protected Japanese gun emplacements. Lead tanks, always the most dangerous ones to be in, would speed up around the curve to stir up a big cloud of dust, obscuring the tanks that followed.

Night attacks finally waned after two weeks and it became obvious that the Japanese besiegers were in terrible shape, famished, ill, their ranks decimated. The breakthrough happened on 24 February when 5th Indian Division troops with A Squadron tanks of the 25th Dragoons pushed through the Ngakyedauk Pass to the Box. Tank driver Norman Bowdler told his IWM interviewer, “C Squadron forced their way up from our side. We were on the Box side… And A Squadron and the rest of them came up from the coastal side and we met at the top.” As if completing a magic trick, the tanks released themselves from their diabolical Box.

The Battle of the Admin Box was enormously significant for the Allies: their first victory against the Japanese in Burma, who would never be quite so feared again. Later in 1944 Allied victories at Kohima and Imphal (northeast India) as well as guerrilla action by indigenous Chin fighters in western Burma would conclusively repel the Japanese invasion of India. The Allies were able to launch a seaborne invasion and take complete control of Arakan in early 1945.

Northern Arakan’s landscape was left splintered, cratered, embedded with unexploded bombs, as much of Burma would be during the war. Had Clive wished to paint the mango trees, the bamboo houses when he first arrived? Had he hated the relentless loss of lives during the siege? Did he view the Japanese soldiers as exploited working class pawns of their fascist leaders? Or, as was pervasive then, as wild beasts? Did he ever despair of returning home to Noreen and Rosa?

Clive had always made the best of difficult situations. He found friends wherever he went and Tony Gilbert, his Spanish Civil War prison-mate and co-conspirator with Indian Communists was also in the Box with another regiment. Surviving Burma, Gilbert would stay active in anti-colonial and anti-racist causes for decades after the war.

More than 5,000 Japanese attackers did not survive the Battle of the Admin Box. British/Indian/Gurkha defenders suffered over 3,500 casualties (killed, missing, wounded, injured, ill) during the Admin Box and related assaults. Severe “psychiatric casualties” were a result of the siege. Those killed included eleven of the 25th Dragoons, two of whom died after the breakthrough: Clive on 25 February and William Graham of C Squadron on 26 February.

![]()

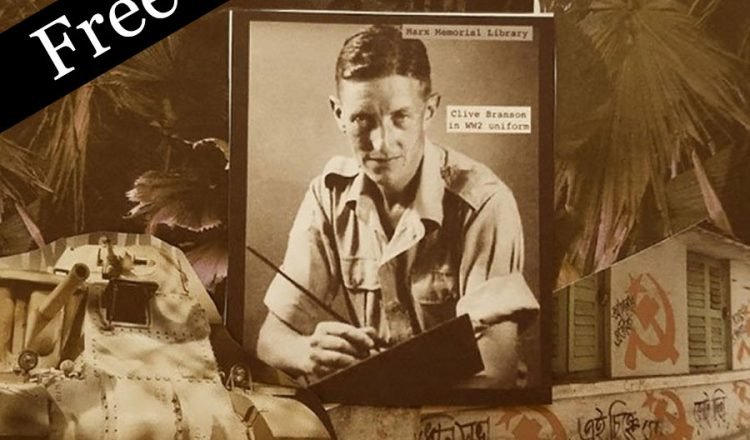

- Tags: Clive Branson, Edith Mirante, Free to read, India, Myanmar