Welcome to the Mekong Review Weekly, our weekly musing on politics, arts, culture and anything else to have caught our attention in the previous seven days. We welcome submissions and ideas and look forward to sparking lively discussions.

Thoughts, tips and comments welcome. Reach out to us on email: weekly@mekongreview.com or Twitter: @MekongReview

To sign up for the newsletter, click here

c

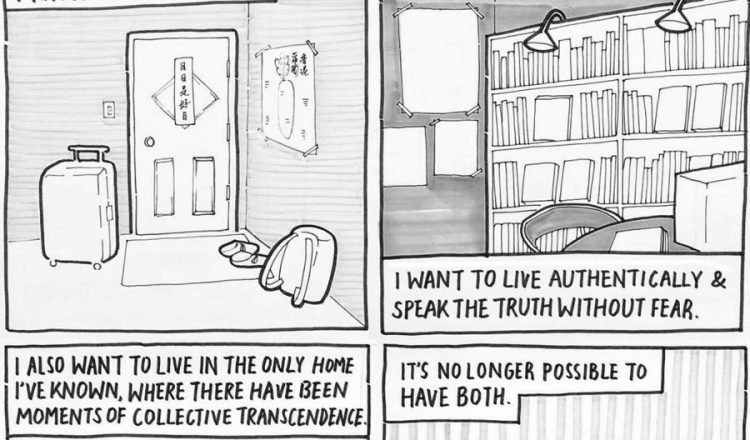

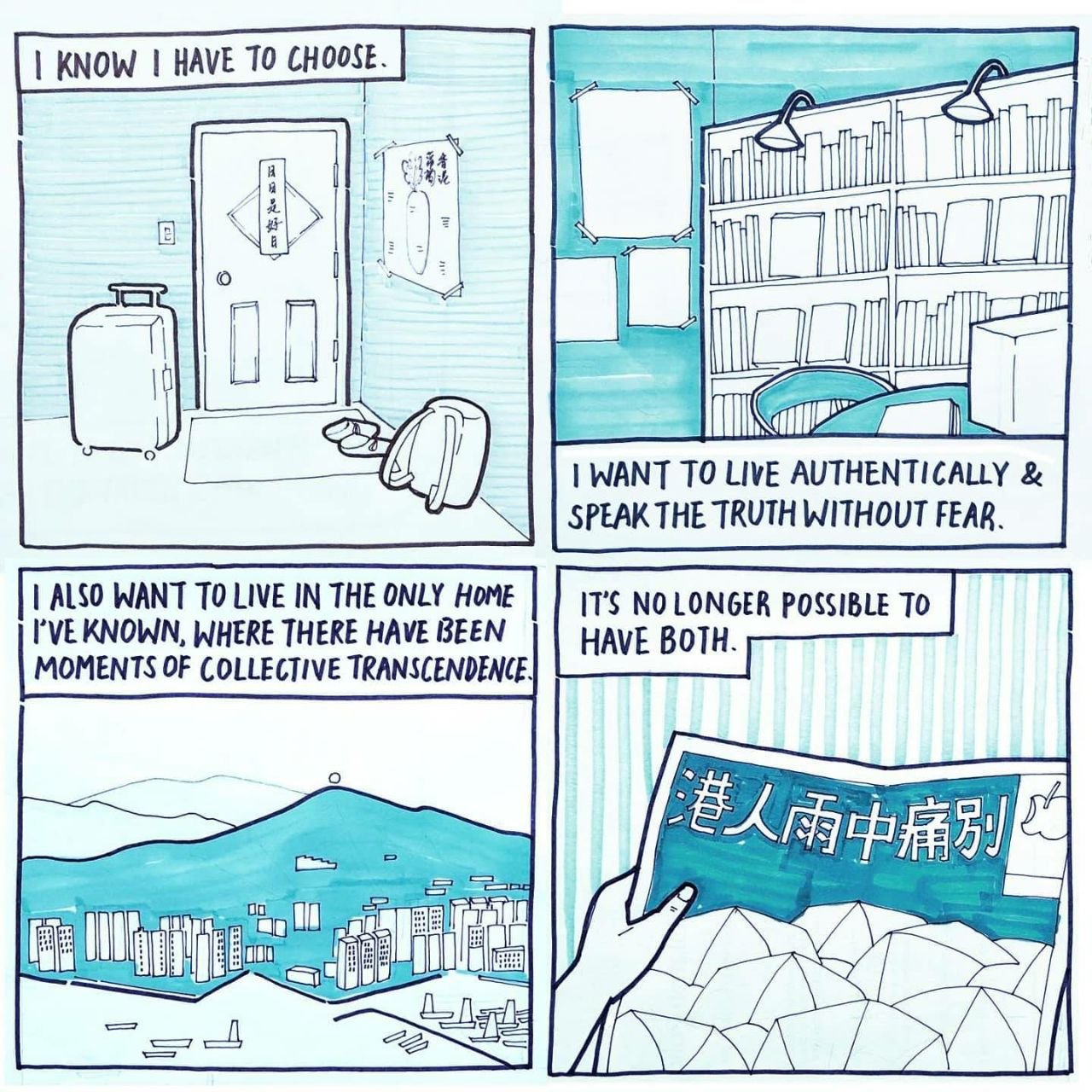

A quieting Hong Kong

The wholesale reshaping of Hong Kong’s civil society continues apace. From politics to NGOs to the arts and culture, every sector of society is feeling the impact of the new national security regime.

The dissolution of civil society organisations that have been decades-long fixtures on the community landscape has become a regular occurrence. Recent victims include the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China (organisers of the annual 4 June vigils for over 30 years), the Civil Human Rights Front (organisers of the annual 1 July protest marches for almost 20 years), and the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, whose members last weekend voted to dissolve the 48-year- old organisation. The PTU, which represents 100,000 teachers, had been accused by government officials and the pro-Beijing press of undermining national security. On Monday, the government warned that any charitable organisations found to have used their resources to support or promote activities ‘contrary to the interests of national security’ would be stripped of their charitable status.

Numerous prominent political and cultural figures have announced their moves into exile. Most recent to join this trend have included activist artist Kacey Wong; one of the filmmakers of the acclaimed Ten Years cinema anthology, Ng Ka Leung; and vice-chairman of the Democratic Party, Lee Wing-tat.

Police stormed a private screening of a movie by director Kiwi Chow on public health and licensing grounds. The screening had been organised by a pro-democracy local councillor; Chow’s protest documentary had recently screened at Cannes. This came as the government announced new amendments that provide for the censorship of films on national security grounds, and impose punishments of up to 3 years imprisonment for illegal film screenings.

But the latest victim of the changes in Hong Kong’s cultural scene hits particularly close to home: one of the Mekong Review’s staunchest friends in Hong Kong, independent bookstore Bleak House Books, has announced their impending closure. In a poignant blog post, proprietor Albert Wan wrote: ‘Given the state of politics in Hong Kong, [my wife] Jenny and I can no longer see a life for ourselves and our children in this city, at least in the near future.’ (You can read poet and editor Lok Man Law’s 2019 interview with Albert in the Mekong Review here.)

It is the steady accumulation of these numerous, small changes—one less independent book store, one less NGO, one less artist, one less cinema screening—that collectively build up to the picture of the real tragedy of a Hong Kong remade under authoritarian rule.

Notebook

How to decolonise

Bhakti Shringarpure

As an academic working in the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge for the last two decades, Priyamvada Gopal could easily spend her days doing the usual and the expected at a posh university with freshly trimmed lawns and Gothic chapels. Instead, she has been the subject of virulent hatred, positioned at the centre of media controversies, subjected to both serious slander and laughably petty accusations. Even though Gopal has published critical work on the British Empire since the start of her career, the past few years have found her involved in student protests for the decolonisation of universities and, as a result, subjected to disturbing, neoconservative attacks.

Gopal has remained firm against her detractors, resisting what she calls the ‘fake culture wars’ being generated around her, and displaying in the process a sardonic and unsparing wit. Though the dust keeps swirling, Gopal has continued to produce important writing. Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent, published last year, is a magisterial volume that complicates and expands our understanding of the histories of dissent during the colonial period. Her recent article, ‘On Decolonisation and the University’, published in the journal Textual Practice, also offers clarity on many of the debates raging at American and European universities today.

When we spoke on Zoom, I had expected to meet the intimidating version of Gopal often observed on social media. But instead, I found her relaxed, charming, and easy to talk to.

Insurgent Empire seems to speak directly to a very precarious moment in British history, by which I mean the vigorous defence of empire going on in certain circles these days. I’m not saying this hasn’t happened before, but with Brexit and so on, there’s a real revival of imperial nostalgia, and you’ve been at the front lines of speaking and writing about it. Did these events influence you as you wrote your book?

Yeah, they very much did. What feels to people outside Britain as new and in your face—that is, this energy that goes into renewed defences of the British Empire—has actually been brewing for at least a decade or longer. It’s become very salient because of Brexit, Boris Johnson, and the Trump years. This inability to question or even understand the empire except through an attenuated historical mythology has been around for a very long time. In fact, C.L.R. James, whom I discuss in the book, talks about the mythologies of empire, and he was writing in the early 1960s. He describes this myth of a benevolent and giving empire as being in tatters, and yet that myth is still around. He talks about the ways in which the tatters are taken and stitched up to make the myth new again. And that is exactly right. So, the mythology of the benevolent empire has never gone away and is very salient for me in terms of public discussions in Britain. But I wanted to think about it and define it differently from just saying, ‘Well, here’s the postcolonial version of empire, right, the bad empire versus the good one of the myth’.

Read more here

Check it out:

Poet and writer Phina So guest edited the latest issue of chogwa, a quarterly magazine that typically features a single Korean poem with multiple English translations. The August issue explores the poem ‘Chhnang’ by Chin Meas through 17 excellent translations, as well as an essay by Phina So and art by Sophal Neak. View the full issue here. (ht/ NYSEAN)

![]()

- Tags: Newsletter