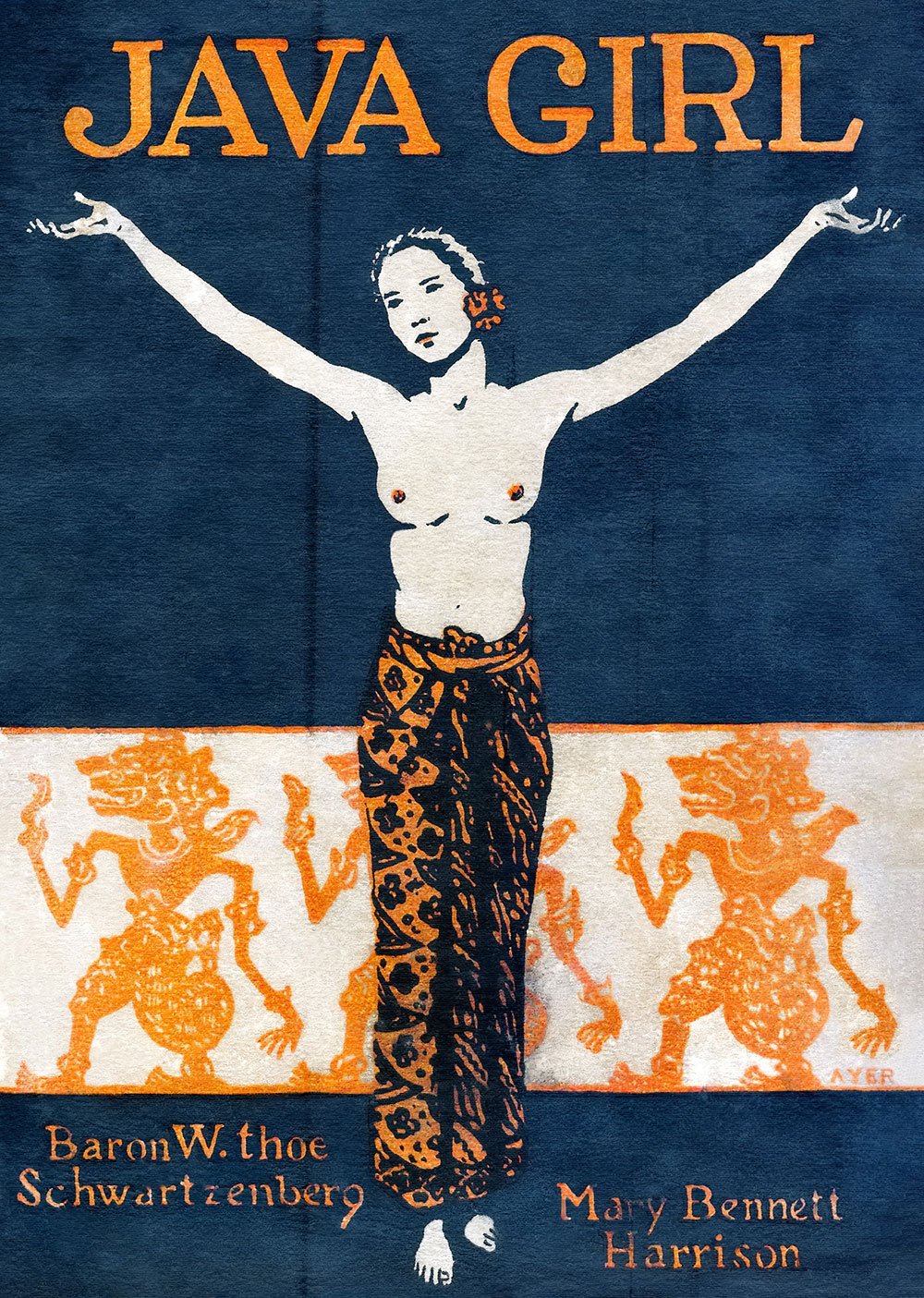

Java Girl: A Romance of the Dutch East Indies

Baron Willem Herman Thoe Schwartzenberg

DatAsia Press: 2020

.

The colonial era in Southeast Asia produced a library worth of travel books and novels written by Western visitors who briefly passed through. The formulas were quickly established. From Sri Lanka to French Indochina, the tropical scenery and local traditions served as lush stage setting for the oft-romantic ramblings of the white colonisers. The markets were always colourful and teeming, the male natives lazy and shiftless, the females salacious, both genders perpetually scheming. Yet there was a backlash from European writers long before Edward Said codified and condemned this literature as hopelessly entwined with colonial hegemony in his study Orientalism in 1978.

A seminal voice was Victor Segalen (1878–1919), a French naval doctor interested in the impact of colonialism on native people. Segalen attempted to identify a mode in which to express such encounters that did not follow the clichés of popular writers, whom he refers to as ‘pimps of the sensations of diversity’, purveyors of an empty exoticism to which readers could cheaply thrill.

Segalen’s unfinished notes, which he styled an ‘aesthetics of diversity’, were published posthumously in 1978 as Essai sur l’exotisme. Significantly, Segalen recognised the paradox that while colonialism permanently altered the cultures it touched from the very moment of contact, it also exposed foreign travellers to those cultures, and Segalen believed that these experiences, if properly understood, could genuinely expand one’s perception of both ‘self’ and ‘other’.

It is a difficult aesthetic mode to follow, and Segalen, who wrote about his experiences living in China, often fails to live up to in his own high standard (Said tossed him onto the dust heap as just another Orientalist). Nonetheless, Segalen’s approach, subjective and fragmentary as it may be, offers a way of reading colonial representations of Southeast Asia as works of social history, focusing less on the concocted ambiences and torrid romantic plots and instead on the assumptions and preoccupations of the authors and their audiences. There is no point in debating or defending such books against charges of Orientalism: all are written from the point of view of the coloniser. Instead, their value lies in their ability to demystify the colonial experience and re-evaluate its modern parallels.

Which brings into our view the all-but-forgotten novel Java Girl: A Romance of the Dutch East Indies. Published in 1931 in New York, it predictably follows Orientalist tropes and patterns, but nonetheless shines a bright light on a colonial experience that is echoed and repeated to this day: the mingling of the privileged white male with the impoverished yet beautiful native girl. Java Girl has been recently reissued by DatAsia Press in a sumptuous production that includes hundreds of illustrations and a handful of scholarly appendices, edited by Kent Davis, a self-styled ‘literary archaeologist’.

The book’s backstory is as intriguing as the plot. The author bears the impressive name of Baron Willem Herman Thoe Schwartzenberg. Born to reduced nobility, he travelled to Java as a young man at the turn of the century to work on sugar and tea plantations, then drifted away after a few years. Following dubious ventures in South America, the Baron washed up in California where he worked in a bank and later opened a travel agency.

Davis speculates that the Baron kept notes from his time in Java and, struggling to form them into a novel, turned to a journalist and playwright named Mary Bennett Harrison, whose name also appears on the book jacket. The final product was lavish, sporting a batik fabric cover and a copper stamped spine. It is now a very rare book, indicating a limited print run and leading Davis to speculate that the Baron paid for the production of the book as a sort of memento. There were few reviews. A one-liner in the Atlantic Monthly read: ‘White man—brown girl: a tale of exotic passion and oriental witchery’.

The plot revolves around the colonial system of minor wives, which existed in some form or other across all the European colonies in Asia; that is, the taking of a local woman as a housekeeper and concubine. Known as con gai in Vietnam and nyai in the Dutch Indies, the patterns varied slightly from place to place but the outcomes were usually the same. The women were more often than not discarded when the white man either returned to Europe or found a more suitable match. Java Girl depicts a different outcome.

The hero, René, an idealised version of the author, arrives in Java leaving a fiancée in Holland. He swears never to touch a native girl but circumstances change quickly, of course, and soon his young and pretty house servant Adinda is elevated to the status of nyai. Not long after, René starts to fall in love with her.

A sensitive soul, René undergoes much agony in deciding the correct course of action. He is assured that when he eventually abandons her, the native people would accept her back with high respect (the reality was quite the opposite, and far more brutal for mixed-race children). What should he do?

Role models abound. This man keeps a native girl not as a nyai but as his mistress in town, where she lives with their child; this man took a white wife and left his nyai, who promptly dosed him with slow acting poison; this man’s Dutch wife is in residence but he nonetheless keeps a native sidepiece; René’s own brother has a nyai of whom he is fond, but swears that the native women can’t feel love in the European sense. Don’t be fooled.

These are not just debates of another era. They can be overheard today in Western ex-pat bars from Bangkok to Bali, Pattaya to Phnom Penh. ‘Do the women here feel love like the girls back home?’ ‘They have incredible sensual charms, sure, and they are far more devoted, and more jealous, than Western girls, but does the sensual attention and the devotion and the jealousy all add up to love?’ ‘No, no, mate, it’s like the old saying, “West is West and East is East and never the two shall meet … Except between the sheets.”’ Laughter. In Java Girl, Réne internalises this conversation, assuming all the voices in his indecision.

Despite the uncertainties, in the end he chooses to stay with Adinda, and the two live happily ever after. The final line of the book: Java had won.

In reality, the Baron lived out his days in sunny Santa Barbara married to a Western woman, but perhaps there was a love affair from his youth that he couldn’t forget, a Javanese girl he had abandoned and regretted for decades. Perhaps not. We’ll never know. His fetish for Javanese women, however, is quite apparent.

Davis’s book explores the fetishising of Indonesian women by including a long appendix on the history of photography in Indonesia and the appearance of women in period photographs and postcards. He discovered one girl who shows up repeatedly in images by celebrated Javanese photographer Kassian Céphas, and it is her image he assigns the role of illustrating Adinda on the book cover.

Another long appendix covers Malay poisons. Modern readers may dismiss that element as colonial stereotype, but the wise old woman who sells love potions or poisons (one for every occasion) is in fact a stock character in locally produced Malay Archipelago narratives up through the early film era.

Occasionally Davis’s editorialising gets the better of him. The narrative is brought to a halt for a page-length footnote about the history of the word freelance merely because a character utters it. Sometimes the illustrations are distracting.

Davis made use of the online archive at Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands to ‘show the actual locations, views, villages and cities you will visit in the story,’ he says, which adds much value when the images are accurate but can become jarring when errors occur. The image on page four does not depict the bay at Cirebon, for example. Most distressing, an image of the fanciful house built by the famed Javanese painter Raden Saleh in Batavia is given the caption of ‘The Mansion [in Bogor] dated from the time of the coffee barons had made their fortunes on the island.’ Saleh and his legacy are simply erased (the house still stands in Jakarta).

Yet such errors are infrequent and DatAsia deserves kudos for bringing Java Girl back to life. The resuscitation was clearly a labour of love for Davis, whom, as he announces, is married to a Thai, with whom he founded DatAsia and engages in charity work in Southeast Asia.

The phenomenon of the nyai is of interest to scholars and this work contributes to the study of the literary genre of the colonial nyai novel. Its primary audience, however, is Western ex-pats in Southeast Asia that find themselves cohabitating with, or married to, local women. For us, René’s struggles and self-doubts remain as pertinent today as they were a century ago.

![]()