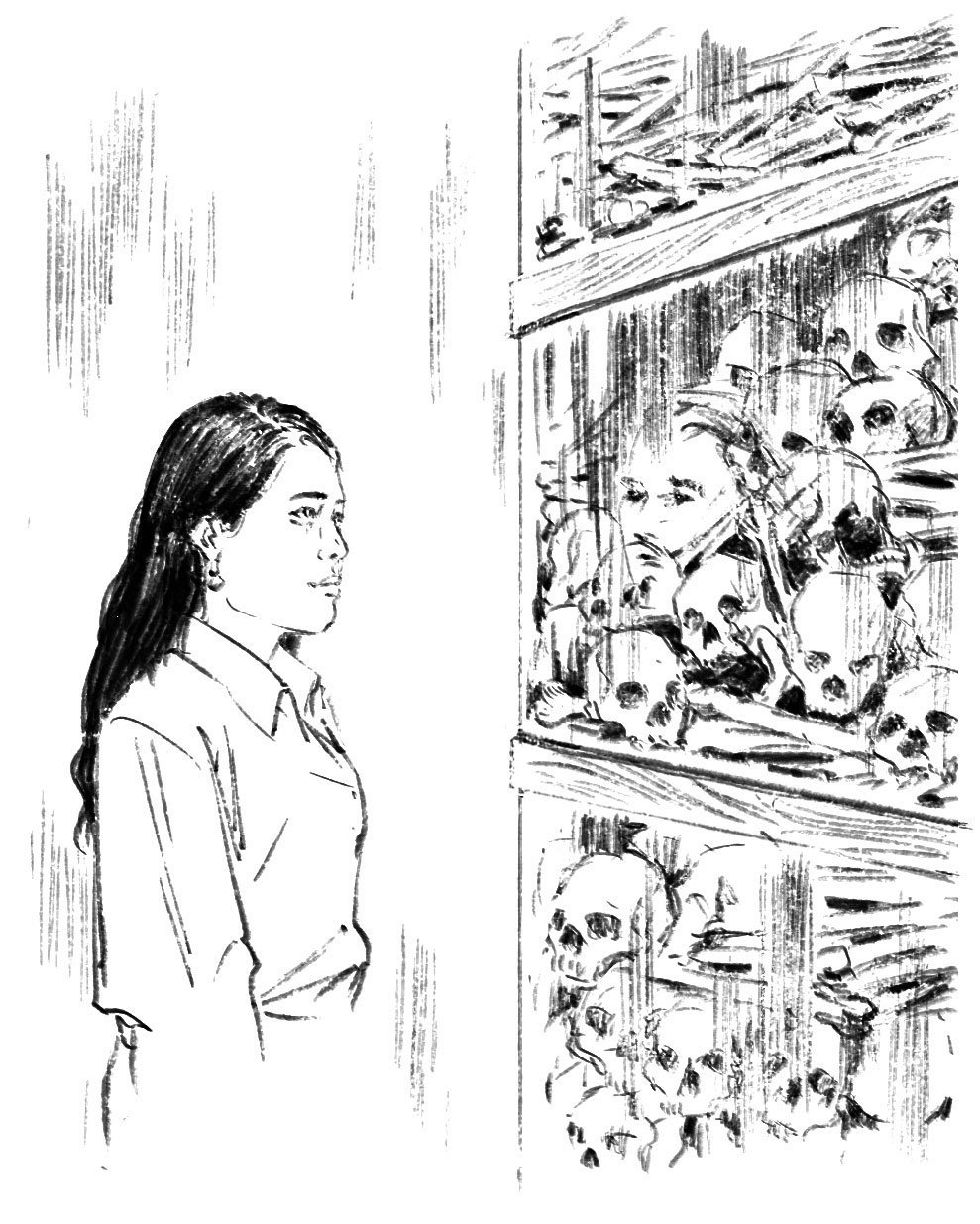

One night, sometime in 2015, I was talking to a young Cambodian I had just met through a friend. When the Khmer Rouge Tribunal came up in our conversation, he told me a story about his mother: how she had lost her family during the reign of terror (an estimated 1.7 million people died of starvation or illness, or were executed); how she had been abused (sexual abuse, forced marriage and forced labour were common); and how she had hoped that talking about her experience would bring her relief. When staff from the court visited her at her home, in the countryside, it was anticlimactic. As her son told me, talking about the atrocities didn’t make her feel better. She was disappointed and ended the interview early.

But, then, there was the other story. In September 2016, I was writing up a particularly grim account of a woman who had been forced to marry a man she had never met and whom she didn’t like. Two days before the union, five men raped her at gunpoint. She told the court: “They threatened that if I said anything I would be killed … I want to say it now, because I want to tell everyone — to tell the world — how I was mistreated at the time.”

After the hearing that day, a lawyer invited me to a private meeting with some victims (“civil parties”, in court parlance) of the Khmer Rouge atrocities. Present was the woman who had just testified about her rape and forced marriage. In her testimony, she also mentioned having had to sing revolutionary songs in front of Nuon Chea, also known as Brother Number Two in the Khmer Rouge hierarchy. Standing in a grey room filled with plain tables and a dozen chairs, she sang Red Sun Song. I didn’t understand the lyrics, but it didn’t matter. Everyone was deeply moved. It was an important moment. And it felt right.

March is one of the hottest months in Cambodia. The sun was blazing down on Phnom Penh as my plane descended, the cabin jolting as the wheels hit the tarmac. I was soon to start a four-month internship with the prosecution at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, formally known as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. The ECCC was set up as a hybrid court — a mix of Cambodian and international — to try the senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime, which lasted from April 1975 to January 1979.

When my time as an intern was up, I became a court monitor for Northwestern University’s Cambodia Tribunal Monitor, when that ended I joined the Phnom Penh Post, and when that paper was sold off to the current owner in 2018, I started freelancing. Through each of these jobs I saw the tribunal through a different lens. Ironically, each added a layer of opacity. Along the way, my position on the question everyone asks about tribunal — whether it was worth it — has also changed. Where I once had been certain that the court was, despite its many flaws, worth it, now I’m not so sure.

When I was working for the court, friends and acquaintances would sometimes ask, in accusatory tones, why the process was taking so long. And I got it — since 2006, when the court started, only three senior leaders of the murderous regime, including Nuon Chea, the second in command after Pol Pot, had received sentences. Other cases are still under review, but with the government opposing any further trials they are unlikely to see the light of day.

Frustrated, some would take it out on the lawyers. “Are they doing anything at all?” they would ask mockingly. I would have none of it. “The lawyers go to the office at dawn and often stay until late at night. They work on the weekends,” I would tell them. During my time at the prosecutor’s office, I saw how hard everyone worked.

Over the years, the worn-down faces of my court friends have become a familiar sight. Some have burnt out and many have had therapy. On top of the stressful environment, the strain of having to deal with mass atrocities every day would take its toll. Emotional support at the court is meagre, and one Cambodian intern quit because she could no longer bear the nature of the crimes. She suffered severe depression for months afterwards. I similarly felt dragged down. In an email to a friend during my time as a trial monitor, I wrote that I felt “quite unbalanced, stressed and rather disoriented”.

When I worked at the Phnom Penh Post, I avoided reporting on the court. I would cite a possible conflict of interest, having worked on most of the cases at some point. In truth, though, I just wanted a break from it. In fact, I didn’t want anything to do with it. But with the distance came the cynicism. Among my journalist colleagues were those who didn’t believe in the court. I too came to adopt a negative view of it, wondering whether it was good for anything at all.

There were plenty of reasons to be negative, including the cost. The court has proven incredibly expensive, and millions of dollars of assistance have poured in from all over the world. My home country, Germany, is one of the largest donors — perhaps to further remedy its own past. In a developing country like Cambodia, the money could well have been invested in something more tangible. But this argument doesn’t gel with how international development aid works. If the money hadn’t been invested in the court, it wouldn’t necessarily have been invested in something useful, or been invested at all.

One of the tribunal’s most outspoken critics is Victor Koppe, the defence counsel for Nuon Chea (who died last year). While criticising the court as “a farce” — he even accused the French judge Jean-Marc Lavergne of being the “ultimate combination of bias, incompetence and dumbness” — he was also happy to accept a monthly salary of tens of thousands of US dollars.

And yet Koppe has a point. Political interference makes independent judgements difficult. Some witnesses who should have testified weren’t called, and the national prosecutor and judges seem to toe the line of the prime minister, Hun Sen, in opposing additional trials. This puts a significant dent in the reputation of the court.

Apart from questions about its legitimacy, the court is also immersed in internal controversies, from intern strikes — its interns aren’t paid — to the sexual harassment of staff members. Yet, despite all these controversies, I still cannot bring myself to say, or think, that the court has been pointless.

When I flew into Phnom Penh on that hot afternoon five years ago, I didn’t imagine that I would still be here today and still be thinking about the tribunal.

I recall interviewing a woman in March 2018 whose father was killed at the notorious Tuol Sleng prison, or S-21. During the interview, she started crying. For her, finding records of what had happened to her father was an important step towards closure. The court helped her with that — she could look for specific people mentioned in testimonies and go over interviews with prison staff. Every now and then she would email me to ask whether I had any new information.

Her story and that of the woman who was raped and forced to marry someone she didn’t love, and those of many others, made the court and its purpose real. As a court monitor who had to follow every proceeding, I watched plenty of other witnesses and civil parties express the same feelings of relief and genuine gratitude. They would thank the court. Scores of them would say that it was the first time they had told their story publicly, and that doing so was important to them.

In addition to giving victims some sort of relief, there’s the work of documenting what happened during those three years, eight months and twenty days under the Khmer Rouge — at least that’s one thing I can still believe in.

As Nicholas Koumjian, former co-prosecutor at the tribunal, put it in an interview with the Documentation Center of Cambodia: “I think we showed through the trials that have taken place so far a representative example of what happened in all these worksites and cooperatives, how people were treated, how people were forced to marry by the regime and forced to consummate those marriages without the free consent of either partner. We showed the torture centres, the security centres, and how the paranoia of the regime led to such horrible tortures and killings and the great numbers of deaths of all those that the regime considered in any way suspect.”

![]()

- Tags: Cambodia, Free to read, Leonie Kijewski