Anand Panyarachun and the Making of Modern Thailand

Dominic Faulder

Editions Didier Millet: 2018

.

Anand Panyarachun and the Making of Modern Thailand, by long-time Bangkok journalist Dominic Faulder, covers Anand Panyarachun’s life and work as a diplomat, prime minister (1991-92), company chairman and philanthropist. As the book’s title indicates, Anand’s career also provides a useful lens through which to view a half-century of Thai history. The book includes interviews with many of the key actors in the events that have made Thailand what it is today. As Faulder notes, “The benefit of writing a book about Anand is that many people are willing to open their doors to talk about him; this kind of access is rare in Thailand.”

Although I covered parts of Anand’s career when I was a journalist for United Press International, and later worked closely with him at the Kenan Institute Asia, Faulder’s book provided me with more insight into Anand’s character. The author presents a man of rationality and integrity who set high standards for himself and for those working with him. Throughout his career Anand, now eighty-six, took on a variety of roles, bringing his concern for the public good to each of them.

As the book reveals, Anand was self-confident and decisive, and did not suffer fools easily; he was often straightforward in exposing any foolishness he observed. Although he made enemies he also gained public support, because most people could see that his bluntness was intended to serve the greater good. They could also see that he recognised the advantages his privileged upbringing had given him and sought to understand and empathise with ordinary Thais. In short, Anand was elite without being elitist.

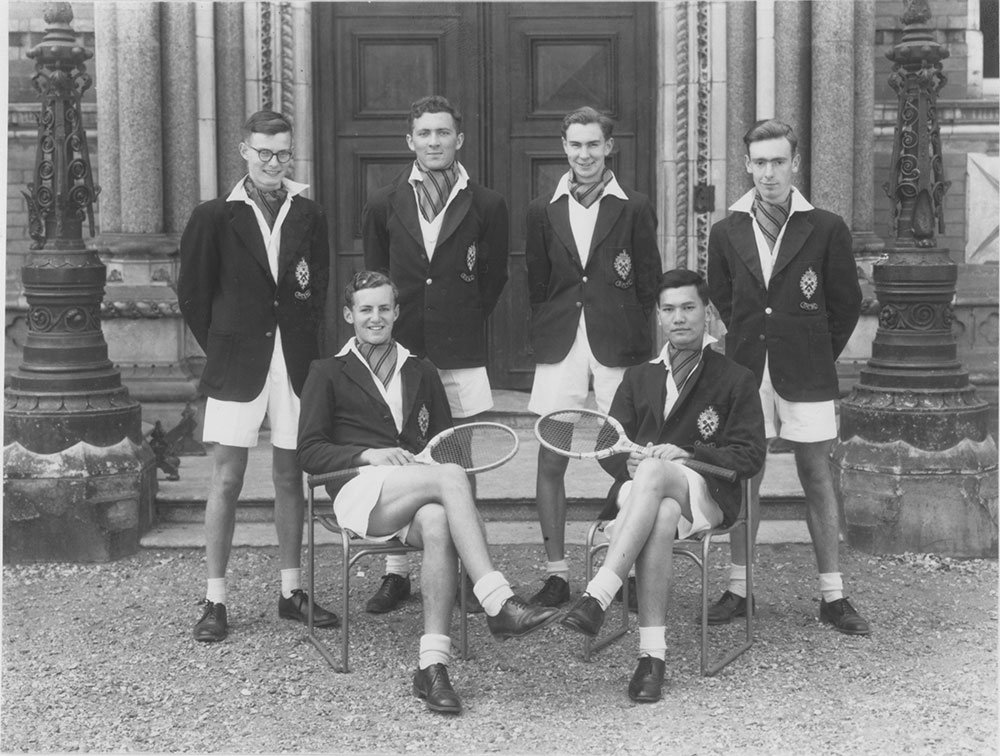

Faulder gives a thorough account of Anand’s early life as a student in England and shows how the bonds he developed with fellow overseas Thai students proved valuable in later years, when he rose to positions of power. The background on Anand’s family and the particular importance of his father, Sern, is useful in understanding the man himself. Sern, the son of a high-ranking official of Mon ancestry, won a king’s scholarship to study in England, before being called back to Thailand to serve in the Ministry of Education, later taking charge of all the royal schools; to teach as a professor at the Civil Service College; and to become the top civil servant in the ministry. After the coup that overthrew the traditional monarchy in 1932, Sern became a businessman and publisher, occupations into which his son would also one day enter.

The highlight of the book is a detailed account of Anand’s two terms as prime minister. Faulder sheds light on the relationship between Anand and army commander General Suchinda, who appointed him in 1991, after another coup, only to see him sideline key generals and move against some military interests. The book details the Anand government’s considerable achievements during those two brief terms — advancing women’s rights, espousing much needed educational reforms, improving telecommunications infrastructure and saving many thousands of lives through Thailand’s enlightened model for action against AIDS. A share of the credit is given to the ministers who Anand brought into his cabinet. There is also a good discussion of Anand’s work to help write Thailand’s 1997 constitution, often considered the best of the many constitutions the country has had.

If there’s a glaring omission in from the book, it’s Anand’s relationship with King Bhumibol Adulyadej. Faulder notes that Anand had numerous meetings with the king, especially as prime minister, and presents other people’s thoughts on the relationship. (One friend described Anand as a “Bhumibolist” rather than a royalist.) However, there is little directly from Anand. As Faulder states in his author’s note, Anand made it clear that matters discussed privately with the king were off limits for the book. This is understandable but unfortunate, as Anand’s views of the king could have contributed to a better understanding of a monarch whose long reign was shadowed by unsubstantiated rumours, excessive adulation and blame. Both the king and Anand were shaped by extensive early education in Europe, and both had to adapt to the complexities of traditional Thai society. Their discussions of Thailand’s problems must have been fascinating.

The author also omits any discussion of Anand’s religious thinking. Faulder notes Anand’s opposition to making Buddhism the state religion during the development of the 1997 constitution and quotes him as saying, “Normally I don’t give money to temples.” Since Buddhism is so important in the thinking of many Thais, it would have been useful to read more on this subject.

For someone often described as part of the traditional elite, Anand holds rather untraditional views. He rejects the idea of “Thainess”, and laments that so many Thais misunderstand their own history and take pride in the glory of a unitary state that never existed. He refutes the common prejudice of many in Bangkok against the Lao ethnic minority, saying he saw them as intelligent and hard-working.

Faulder quotes Anand as appreciating the writings of Thai “radical thinkers”, including Chit Phumisak, Seni Sawaphong, Khamsing Srinawk and Seksan Prasertkul. He decries the abuses of Thailand’s lèse-majesté law and recommends its reform. As head of a commission on the troubles in Thailand’s far south, he went against the views of most military and government leaders, proposing more local autonomy, greater respect for Islam and a bigger role for the Malay language as measures to reduce the violence there. At the same time, Faulder claims Anand rejects the concept of a “network monarchy”, popular among foreign academics, calling this concept “a convoluted, somewhat obsessive conspiracy theory”.

At some 600 pages, Anand Panyarachun and the Making of Modern Thailand is comprehensive and detailed. The book fills a substantial void in English-language biographies of leading Thais, but it does more than that: it uses the life of a significant Thai leader to give us insider accounts of many of the critical developments in recent Thai history. This wealth of material provides an understanding of Thai diplomacy during the Cold War, for example, and of the country’s efforts to adjust to the new reality after the wars in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. But because Faulder’s account is tied to Anand, it has little to say about the impact of change on the people of the countryside, let alone Thailand’s recurring radical movements, the rise and fall of the Thai Communist Party, and much else. All said, this important work will set the standard for biographies of many other significant figures in contemporary Thai history that are long overdue.

![]()