Rohana Abdul Kadir and her two sisters work in a keropok (fish cracker) factory in Kuala Besut, situated near the border of Terengganu and Kelantan on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Through their daily toil of kneading flour and fish, then steaming, slicing and drying keropok, they barely earn enough to support their families. The sisters radiate an unpretentious beauty and carry themselves with a dignified poise despite their harsh living conditions.

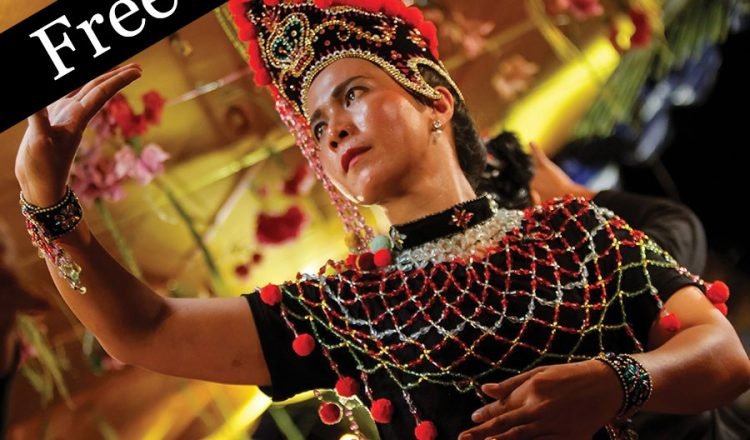

One would never imagine that these three sisters are living custodians of one of Malaysia’s most ancient and resplendent theatrical traditions—the Mak Yong. A Malay dance-drama tradition found primarily in the northeastern Malaysian state of Kelantan and the Pattani region of southern Thailand, Mak Yong was recognised by UNESCO in 2005 as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Encompassing elements of dance, drama, storytelling, music and ritual, the Mak Yong is a women-centred folk tradition nurtured by community bonds.

Rohana, Che Yom and Che Esah are the granddaughters of Che Ning, the late legendary Mak Yong prima donna, and are the inheritors of a lineage that reaches back seven generations. They first learnt the dance from their grandmother when they were little. While Che Ning’s intensity and charisma in performance remain unparalleled, her late husband, Pak Su Mat, was one of the rare male performers who possessed the requisite grace and mastery to take on the protagonist roles in Mak Yong. His younger sister, Che Siti Dollah (fondly known as Mek Ti), and brother, Pak Su Kadir, were also mentored by Che Ning.

Since Che Ning’s passing nearly two decades ago, Mek Ti has become the maternal anchor of the Mak Yong community in Kuala Besut. Now in her eighties, Mek Ti is an embodiment of the traditional power of women in Kelantan, wielded across realms from mythology to local economy.

The traditional power of women in Kelantanese society has been undermined by the cultural politics of the past few decades—a culmination of ideological forces attempting to redefine cultural life. Nowhere is this more evident than in the decades-long official banning of traditional arts by Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS).

In the early 1990s, the PAS government of Kelantan banned the centuries-old cultural traditions of Wayang Kulit, Mak Yong, Main Puteri and Manora on the grounds that they were antithetical to the tenets of Islam. The ban was in essence an attempt to eliminate a part of Malay cultural heritage, redefine the historical identity of the Malay people and impose a rigid interpretation of Islam. The impact of the banning of traditional arts in Kelantan and Terengganu has discouraged the practice and teaching of Wayang Kulit, Mak Yong, Main Puteri and Manora in local communities and robbed an entire generation of young people of their cultural heritage.

The banning of Mak Yong has been particularly symbolic because of the dominant role of women in the tradition. Mak Yong is a traditionally female-centred space where young people are exposed to the power and complexity of the female presence. In this sense, Mak Yong is a site of female power—a strict and deep artistic tradition that affirms the unique and diverse position of women in Kelantan, from sovereign ruler to household authority and economic power. The banning of Mak Yong sends a message to women about their permissible space in society and their reduced freedom of expression as defined by religious authorities.

I first met Mek Ti, Rohana, Che Yom and Che Esah through my work with PUSAKA, a cultural organisation founded by the journalist and cultural historian Eddin Khoo after the bans to revitalise traditional performance. Since the early years of proscription, PAS’s implementation of its cultural policy has gradually grown somewhat half-hearted, revealing its gestural political nature. It is within this grey area that PUSAKA has been able to work closely with traditional artists in Kelantan over the past twenty years to organise countless underground traditional performances, document their art forms and pass down this knowledge to the next generation.

In 2019, the PAS government of Kelantan announced a ‘lifting of the ban’ on Mak Yong. However, the reality is that women are still not officially allowed to perform and traditional arts practitioners in local communities are still subject to the whims of politicians. Only state-sanctioned ‘syariah compliant’ versions of Mak Yong are allowed under this new ruling, which means all ritual aspects are forbidden, women have to ‘tutup aurat’ (dress modestly with no exposed hair or limbs) and gender segregation of performers and audience is imposed. While some applaud this so-called lifting of the ban, others, including women Mak Yong masters of long lineage, see it as little more than political posturing by state authorities and bureaucrats.

The powerful position of women in traditional Kelantanese society reveals itself not only in the realm of traditional arts but also in the conspicuous presence of women in Kelantan’s economic life. The traditional role of women in Kelantan has long been one of household authority and economic power. On his voyage to Kelantan in 1837, the writer Munsyi Abdullah observed that industrious Kelantanese women dominated trade at the marketplace while the men idled their days away with frivolous past times and getting into fights. Even today, women wield more power than men in Kelantan’s local markets and often manage the household finances.

The mythological landscape of Kelantan–Patani is dominated by powerful women who were respected rulers of their kingdoms. Often an amalgamation of the historic and the mythic, these figures are enduring archetypes of feminine strength and spirit. The legendary queen of Kelantan, Che Siti Wan Kembang—believed to have reigned for more than sixty years during the seventeenth century—gained renown for her beauty, wisdom, diplomacy and prowess as a warrior. Her adopted daughter, Puteri Saadong, is said to have reigned as Raja of Jembal and later as Raja of Kelantan. A pair of kijang mas (golden barking deer), a beloved pet of the queen, adorn Kelantan’s royal coat of arms.

Culturally and historically linked to Kelantan, the Sultanate of Patani also saw the ascent to power of several women rulers. The ‘golden age’ of Pattani that spanned the late sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries is associated with four successive sultanahs, Ratu Hijau (The Green Queen), Ratu Biru (The Blue Queen), Ratu Ungu (The Violet Queen) and Ratu Kuning (The Yellow Queen). Several centuries earlier, in 1297, the traveller and scholar Ibn Battuta wrote of his encounter with Urduja, a Muslim warrior princess of Kailukari in the kingdom of Tawalisi, who commanded an army of women and men, spoke a Turkic language and could write in Arabic script. While the locations of Kailukari and Tawalisi remain unknown and disputed, some have speculated that Kailukari may refer to Kuala Krai in Kelantan.

In contrast to Che Siti Wan Kembang, Puteri Saadong embodies the archetype of tragic heroine in Kelantan mythology. She is said to have sacrificed her freedom for the sake of her kingdom and people. When King Narai of Siam attacked Kelantan, Puteri Saadong was captured and her husband Raja Abdullah was to be killed. To spare her husband’s life, and to halt the attack on her beloved kingdom, Puteri Saadong let herself be taken to Ayutthaya to become a concubine in the royal court. She asked Raja Abdullah to wait for her and not to remarry. According to the legend, Puteri Saadong possessed mystical powers: each time King Narai tried to bed her, he was struck down by a terrible illness. After several years, King Narai begged Puteri Saadong to cure him, which she did on condition that he release her from captivity. Upon her return to Kelantan, Puteri Saadong discovered that Raja Abdullah had remarried, despite his promise to her. In a fit of rage at his betrayal, Puteri Saadong drew her cucuk sanggul (hairpin) and plunged it into Raja Abdullah’s heart. Overcome with despair, Puteri Saadong renounced her worldly power, leaving her palace for the mountains of Kelantan, where she is still said to wander.

Symbolically, Puteri Saadong represents spiritual feminine power that resists and subverts mundane political power. The complexity of her character encompasses elements of sacrifice, courage, passion, regret and melancholy. She also embodies aspects of both healer and patient—the Main Puteri healing tradition of Kelantan is said, by some Tok Puteri (shamans), to have been created to console Puteri Saadong’s grieving spirit.

The female cultural custodians of Kelantan are not powerless victims—their spirit remains defiant, resilient and resourceful. Despite the restrictions, quiet performances of these banned traditions continue. Communities continue to practise these traditions because they are deeply meaningful to their lives. Ultimately, culture is stronger than politics, and the cultural traditions of Kelantan will survive despite the decades of political proscription.

In the words of Mek Ti: “No man-made law can break the spirit of Kelantanese women. The powerful heritage of our ancestors runs deep in our veins, and will live on in our daughters and granddaughters.”

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Issue 31, Malaysia, Pauline Fan