The Cambodian People’s Party’s Turn to Hegemonic Authoritarianism: Strategies and Envisaged Futures Contemporary Southeast Asia 43, No. 2

Neil Loughlin and Astrid Norén-Nilsson (eds)

ISEAS: 2021

.

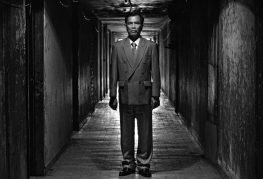

If politics is a zero-sum game, Sam Rainsy, the former opposition leader in Cambodia, is a failure. Back in 2013, when Rainsy was relevant, throngs of supporters were waiting wherever he went, ready to be stirred into a nationalist fervour. One balmy July day, I was covering the Cambodia National Rescue Party’s (CNRP’s) campaign caravan as it stopped outside the central market in Siem Reap city. Rainsy grabbed a microphone and complained that he was tired of eating Vietnamese sour soup. The crowd of thousands roared him on. ‘This time we need to eat samlor kor kou,’ Rainsy said, evoking a traditional Cambodian soup, and again the faithful erupted. After an hour or so, Rainsy and his entourage rolled on. The crowd seemed satiated, and maybe even optimistic—foolishly.

Prime Minister Hun Sen, the Vietnamese soup in this metaphor, won that election and remains firmly in power. Rainsy is exiled in Paris, more likely eating sautéed lamb brains, his favourite food. If one allows for incremental victories, Rainsy has scored plenty of points over the years—higher pay for garment workers, public control of Angkor Wat, pledges to curb deforestation. And Rainsy’s party came so close to winning the 2013 election that Hun Sen was forced to endure months of public humiliation and a brief dalliance with parliamentary democracy. But those are memories now. When Rainsy’s opposition finally posed a serious threat to Hun Sen’s power, it was game over. The prime minister’s loyal courts dissolved the CNRP. His one-party parliament outlawed the main opposition party. And his armed forces reclaimed the streets.