Impermanence: An Anthropologist of Thailand and Asia

Charles Keyes

Silkworm Books: 2019

.

The first thing about this memoir that piqued my interest was its title. Impermanence is not a concept that has much traction in the West, much less in Christianity. It is implicit in Heraclitus’ dictum that one can never step into the same river twice, but the Christian West has been shaped by belief in revelation as the source of absolute truth. Science is a bit less dogmatic: as Karl Popper pointed out, we can never be absolutely certain that scientific knowledge is absolutely true. But the curve of theoretical paradigm change is asymptotic, and scientific progress can be measured by its instrumental application: if things work, we can be pretty sure we’ve got some of it right.

The Buddhist view of the world is very different. Impermanence (Pali: anicca) is one of the three core signs of being, the three indelible characteristics of all existence. Charles Keyes nowhere mentions the other two, so we don’t know whether he embraces either or both. One is dukkha, usually misleadingly translated as ‘suffering’ but better understood as ‘unsatisfactoriness’: no matter how joyous life is at any moment, there is no way any human being can avoid sickness, old age and/or death. The other is anatta, meaning absence of any eternal essence in the form of an atman, or soul. For, as the Buddha discovered after seven years of introspective meditation and taught for the rest of his life, all a human being consists of is changing aggregations of material form, perceptions, sensations, thoughts and consciousness.

Impermanence is central to the Buddhist conception of how the world is: think the symbolism of cherry blossoms for the Japanese. For Keyes, it is not the metaphysical concept that matters, however, but the psychological comfort provided by the realisation that all is transient as he copes with the changes he has undergone ‘in status, lifestyle and body’ since retiring, downsizing and being diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease. What we are not told is whether Keyes counts himself as a Buddhist and, if not, how Buddhist concepts like impermanence have influenced the way he has lived his life.

You don’t have to read very far into Keyes’s memoir to recognise that this is a book by a scholar. Even the prelude has footnotes, and there are plenty more along the way, providing information about sources (letters home, diary entries, fieldwork notes, all precisely dated), about the meanings of words and concepts, and about the people Keyes encountered in the course of his career, their interests, their publications and, yes, their status within the spectrum of Southeast Asian studies. The writing is measured, precise, unemotional, the account comprehensive but modest. Keyes shies away from assessing his own contribution to Thai and Southeast Asian studies, though it has been considerable.

Charles Keyes was born in a small town in the cattle country of northwestern Nebraska in October 1937. Soon after, the family moved to Idaho, where ‘Biff’, as he was always called by family and friends, grew up as an outsider, a Presbyterian among majority Mormon classmates. The young Keyes was not an outsider by choice—he joined the Scouts and the YMCA—but more because both at school and later at Nebraska University he was studious and serious and got good grades. Today we would probably call him a nerd.

University set the direction of Keyes’s life. From physics and maths, he gravitated to English and anthropology, took a keen interest in world affairs, actively campaigned for John F. Kennedy on campus and gave up, as he puts it, ‘formal affiliation with any religions’—code, I surmise, for loss of faith. What he took from Christianity was its message of social activism, along with a realisation of the need for ecumenical dialogue across the barriers of belief. Both would be lifelong convictions.

Keyes chose Cornell over Harvard or Chicago to pursue graduate studies in anthropology and, once there, Southeast Asia over the Middle East or the Americas. At the suggestion of his prospective supervisors, he embarked on serious study of Thai language and Buddhism, while at the same time casting around for a topic on which to write a dissertation. Eventually he settled on Isan, the area of northeast Thailand once part of the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang, and arguably then still more Lao than central Thai. The topic he chose to study was the relationship between Isan villagers and the central government as the region became integrated into the Thai state. It was a good choice, and one that kept his interest for half a century, from his first single-authored publication to his last.

Keyes and his wife Jane arrived in Thailand in August 1962 and spent the next four months improving their Thai, making useful contacts and working out where best to conduct fieldwork. Keyes decided on the central Isan province of Mahasarakham, where local officials directed him to the village of Ban Nong Tuen, fifteen kilometres from the provincial capital. There the couple settled in for eighteen months as farang members of the community, taking part in village life, attending ceremonies, making donations, observing and being observed.

Anthropological fieldwork is problematic at the best of times. As the controversy over Margaret Mead’s conclusions about Samoan sexuality illustrate, it is difficult to know whether informants are answering questions accurately and truthfully, or making light of the exchange and relating what they think the anthropologist wants to hear. Very often it’s a bit of both. Though he does mention some misunderstandings, Keyes avoids discussion of this observed-observer problem, while making clear how much he sympathised with—indeed, identified with—‘his’ villagers.

My brother is an anthropologist who lived in Bali for eighteen years. Over that time, his understanding about what he was doing changed. From the first, he immersed himself in everything Balinese, to the point where, after several years, he identified so deeply with Balinese culture that he felt uncomfortable visiting Australia. During this time he made lifelong Balinese friends, but in the end he realised that, no matter how warmly he was accepted into the lives of his Balinese informants, and no matter how long he interacted with them (and their children), a divide that could never be bridged would always exist between how they understood Balinese culture and how he did.

Keyes is too good an anthropologist not to be aware of this. He was frequently reminded by the villagers of Ban Nong Tuen of the gap that existed between them, and how differently each understood the relationship between them—as illustrated, for example, in the villagers’ persistent belief that all farang were immensely wealthy, an impression reinforced by every US citizen they came into contact with, from aid workers to soldiers on a nearby NATO exercise. And of course the Keyes were wealthy, no matter how hard they tried not to show it, and, unlike the villagers, free to leave at any time. So the observer–observed relationship morphed inevitably into a patron–client one, as anyone who knows anything about Lao culture and society might expect. And it was as a patron that to his credit Keyes maintained contact with the villagers of Ban Nong Tuen long after he returned to Cornell, obtained his doctorate, and took up a teaching position at the University of Washington.

The Keyeses came back to Thailand twice more for extended periods: first in 1967 to conduct fieldwork far from Isan on the Burmese border at Mae Sariang; and again in 1972 when Keyes took up a position as visiting professor at the University of Chiang Mai; on each occasion for a couple of years. Significantly, Keyes’s research in Mae Sariang pursued several of the same themes that had interested him in Isan: ethnic relations, the influence of Buddhism, forms of accommodation to government authority.

One thing that was different in Mae Sariang, however, was the presence of five competing denominations of Christian missionaries. In Papua New Guinea, I have seen the divisions such competition can create in previously cohesive communities, and how previously vibrant cultural traditions become impoverished as a result of conversion. Keyes was interested in how conversion could reinforce ethnic identity (in the case of Christianity, and conceivably Islam), or assist in social integration into the Thai state (as missionary activity by Buddhist monks among upland minorities was designed to do).

Keyes refrains from directly criticising Christian missionary activity in Mae Sariang, but the fact that he preferred to attend ceremonies in the local Buddhist wat implies what he thought. Indeed, for the abbot he became both friend and mentor. Keyes has written perceptively on why the Thai are not Christian, in an article in which he argues that ‘historic religions’ like Christianity and Buddhism ‘derive their coherence from a belief in an abstract being [God] or principle [the Law of Karma] under which all other supernatural powers as well as humans are subject’. Historic religions, in other words, rationalise the supernatural—and Christianity and Buddhism do this equally well.

I cite this example because it illustrates what is and is not included in this memoir. What is included is where Keyes went, where he lived, what he did and who he met, plus the cultural and historical background required for context. If the reader wants to know what Keyes thought about what he was doing, how he came to the conclusions he did or how his experiences shaped his beliefs, one must read between the lines. Nowhere, for example, does Keyes explicitly argue for the significance of history in shaping the culture and society that an anthropologist observes during relatively brief fieldwork, though the extent and degree to which history provides a crucial dimension of Keyes’s work on Thailand is by no means common across a discipline that notably entertains structural and functional explanations.

The most fascinating event that Keyes recounts from his years in northern Thailand was not the visit of King Bhumibol and Queen Sirikit, but an expedition accompanying the abbot of the Mae Sariang wat to recover ancient manuscripts that had been discovered in a remote cave. It took days of travel by elephant through mountainous forested country to reach Red Cliff Cave overlooking the Salween River. Some manuscripts had been damaged by robbers and others eaten by termites; but a sufficient number were still intact to fill nine large plastic sacks. This was not just an adventure, but an extraordinary find, for all the manuscripts had been copied prior to the end of the eighteenth century and provided new insights into northern Thai history.

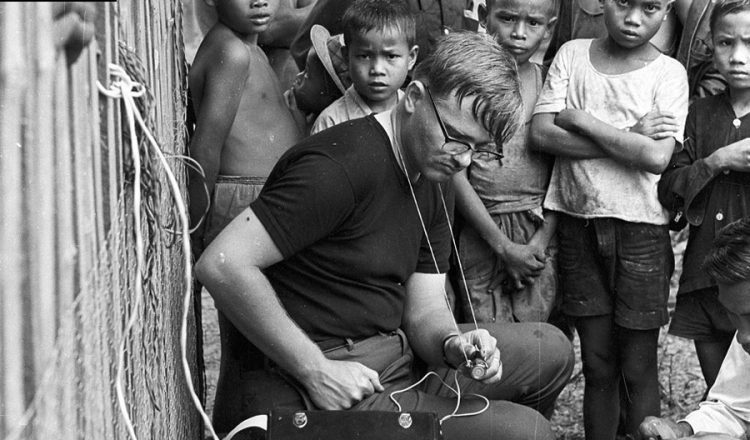

Keyes took up a two-year teaching position in social science at the University of Chiang Mai in July 1972. It was an interesting time to be in Thailand, for the worldwide student protest movement was about to reach Thai university campuses. Of more concern to Keyes than radical student politics, however, were accusations that US academics studying Thai village life were contributing to the anti-communist counterinsurgency campaign, and thus were little more than lackeys of US imperialism. Keyes was so incensed that he agreed to participate in a film narrated in Thai that demonstrated what he, as an anthropologist, had actually been doing.

The last three chapters of the book shift focus from Thailand to the United States, to Keyes’s career as teacher and administrator, as supervisor of both Thai and non-Thai postgraduates, and as an academic ambassador, fostering relations between US and Southeast Asian scholars and institutions. Given the cloud that anthropology was under, Keyes’s first task in taking up a position at the University of Washington was to establish anthropology as a discipline whose value lay in promoting tolerance through revealing the cultural diversity of humankind. And that’s what he continued to do.

What Keyes felt when, in October 1976, the brief experiment in democracy in Thailand was brought to an end with the massacre of student activists in Bangkok, we are not told. But it is evident from his later publications that, from about then on, he took increasing interest in the political dimensions of social and cultural change in Thailand. And it was the political crisis of 2008–10 that brought Keyes’s work full circle, back to the villagers of northeastern Thailand for whom he had such sympathy and affection.

The Red Shirt demonstrations of those years are not covered in this memoir, but I wonder if Keyes recognised the villagers of Ban Nong Tuen among the demonstrators who so persistently struggled to defend the government they had elected. In Finding Their Voice, Keyes argued that the political activism of the Red Shirts, overwhelmingly from northeastern and northern Thailand, is understandable as the outcome of a process of historical change in the course of which ‘traditional’ peasants became ‘cosmopolitan’ citizens through taking advantage of new opportunities in a globalising economy, and that it was this that promoted growing awareness of their political power within a democratic order. He is probably right; but sadly, of course, since Keyes published his analysis, Thai democracy has been all but demolished. I can’t speak for Keyes, but everything in this memoir suggests that he must hope that the impermanence that characterises human existence extends to the current Thai political order, and that Isan voices will be heard again.

![]()

- Tags: Charles Keyes, Issue 19, Martin Stuart-Fox, Thailand