.

The Making of the Modern Philippines: Pieces of a Jigsaw State

Philip Bowring

Bloomsbury: 2022

.

Monetary Authorities: Capitalism and Decolonization in the American Colonial Philippines

Allan E.S Lumba

Duke University Press: 2028

.

The last time I was in the Philippines, I went to see Ferdinand Marcos’ grave. The soldiers guarding the tombstone were napping under a marquee that day, their limbs limply draped like rag dolls across flimsy chairs. Plastic bottles were strewn across the tarmac paths that sliced the burial ground into sections. Off-duty officers from the nearby military base jogged past at a languorous pace. A sign warned in English, ‘Practice driving, biking, dating & other unauthorized activities are prohibited’. The cemetery grasped at pageantry amid the mundane.

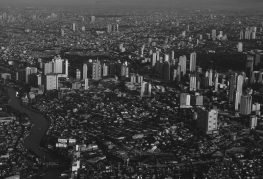

Marcos had been recently interred in Manila. His burial at the centre of the Heroes Cemetery was a sign of the emerging alliance between President Rodrigo Duterte and the Marcos family. Mere weeks after taking office in 2016, Duterte ordered the military to move Marcos’ remains from a bizarre museum-shrine in his home province of Ilocos Norte. His body had lain there, on display in a tomb of glass, since the 1990s. Other presidents had been unwilling to let the dictator be buried alongside the rest of the country’s leaders, as the Marcos family wanted.