Welcome to the Mekong Review Weekly, our weekly musing on politics, arts, culture and anything else to have caught our attention in the previous seven days. We welcome submissions and ideas and look forward to sparking lively discussions.

Thoughts, tips and comments welcome. Reach out to us on email: weekly@mekongreview.com or Twitter: @MekongReview

To sign up for the newsletter, click here

c

A new Cold War?

Last week, Australia joined an elite club after a new security pact put it in line to be the seventh nation in the world to possess nuclear-powered submarines. The surprise AUKUS pact signed by Australia, the US and the UK, aims to ‘bring together our sailors, our scientists, and our industries to maintain and expand our edge in military capabilities and critical technologies, such as cyber, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and undersea domains,’ US President Joe Biden said in the joint announcement made Wednesday.

Conspicuously absent from the statement issued by the three leaders was mention of China. But while the country wasn’t once referred to, there can be no doubt that everything in the pact points back to the emerging superpower.

‘It is impossible to read this as anything other than a response to China’s rise, and a significant escalation of American commitment to that challenge,’ Sam Roggeveen, Director of the Lowy Institute’s International Security Program, wrote in the Lowy Interpreter.

Beijing certainly believes that to be the case. In his Thursday press briefing, China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian referred to the pact as evidence of an ‘outdated Cold War zero-sum mentality and narrow-minded geopolitical perception.’

So, a new Cold War. The announcement has already caused complications for Europe and serious diplomatic fallout with France. But it is Southeast Asia, which bore the brunt of the last Cold War, that stands to bear the repercussions.

‘Many regional countries do not want to be drawn into U.S.-China rivalry,’ Rizal Sukma, a senior researcher at the Jakarta-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and former Indonesia ambassador to Britain, told BenarNews.

Indonesia and Malaysia have expressed concern, Singapore reacted in favour, and the Philippines stressed its desire to ‘maintain good bilateral defense relations with all other countries in the region.’ Other countries have stayed silent.

With tensions rising in the South China Sea, claimant nations should welcome the prospect of stronger ‘friends in the region’ (as the Australian Minister of Defence Peter Dutton told his Filipino counterpart Delfin Lorenzana). But China has been a key ally to much of Southeast Asia, offering billions in trade, investment, and aid. Wary of being used as proxies once again, many will be watching how this plays out in the coming years.

Notebook

Yours and mine

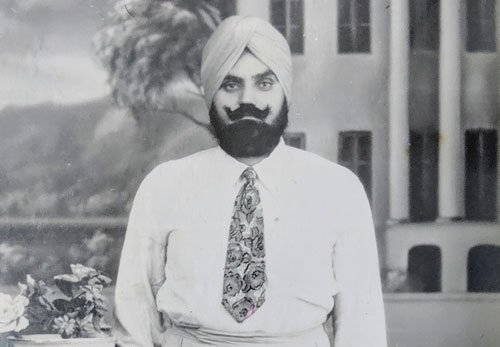

Ashvinder Singh

In the early 1930s, my paternal grandfather, then a fifteen-year-old boy, boarded a train in his drought-stricken village, near the town of Raghuana, Punjab, and made his way to New Delhi and on to Calcutta, the bustling former capital of British-ruled India. The boy was then to board a ship — the only time he would ever do so in his life — to Penang, via Rangoon. As he walked to the vessel, he paused to take in the view. Until that point, he had known only the rivers of his beloved province. What would be his fate in that strange, distant land called Malaya?

This was once a common tale in multiracial Malaysia, the seeds of which were sown as various communities emigrated from the Malay archipelago and China to the Malay Peninsula. From the 1500s onwards, the conquest of the strategic entrepôt Malacca by European powers such as the Portuguese and, later, the Dutch, created the mixed communities that exist today. The British didn’t arrive on the peninsula until 1786, when Captain Francis Light raised the Union Jack in Penang. What followed was a slow but steady subjugation of the nearby territories and kingdoms, resulting in the addition of another colony to the growing British Empire.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there was large-scale immigration to Malaya, mainly for economic reasons. Tin mining attracted swathes of Chinese immigrants, who often toiled (and lived) in inhumane conditions. Most Indian immigrants were drawn by a different commodity — rubber — but some came for business purposes or to join the British police or army. The Malays and other indigenous communities were left alone, for the most part. These communities largely lived parallel lives, with limited interaction with one another — thanks to the all-too-familiar divide and rule strategy of the British. Despite occasional communal problems, Malaya grew increasingly affluent over time.

Read more here

Tune in:

On 20 September at 7pm EST, yours truly will be moderating a talk between Saumya Roy, author of Love and Loss Among the Wastepickers of Mumbai, and Taran Khan, author of Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul. Hosted by Cafe Con Libros, the online discussion is free and open to all.

![]()

- Tags: Newsletter