Welcome to the Mekong Review Weekly, our weekly musing on politics, arts, culture and anything else to have caught our attention in the previous seven days. We welcome submissions and ideas and look forward to sparking lively discussions.

Thoughts, tips and comments welcome. Reach out to us on email: weekly@mekongreview.com or Twitter: @MekongReview

To sign up for the newsletter, click here

c

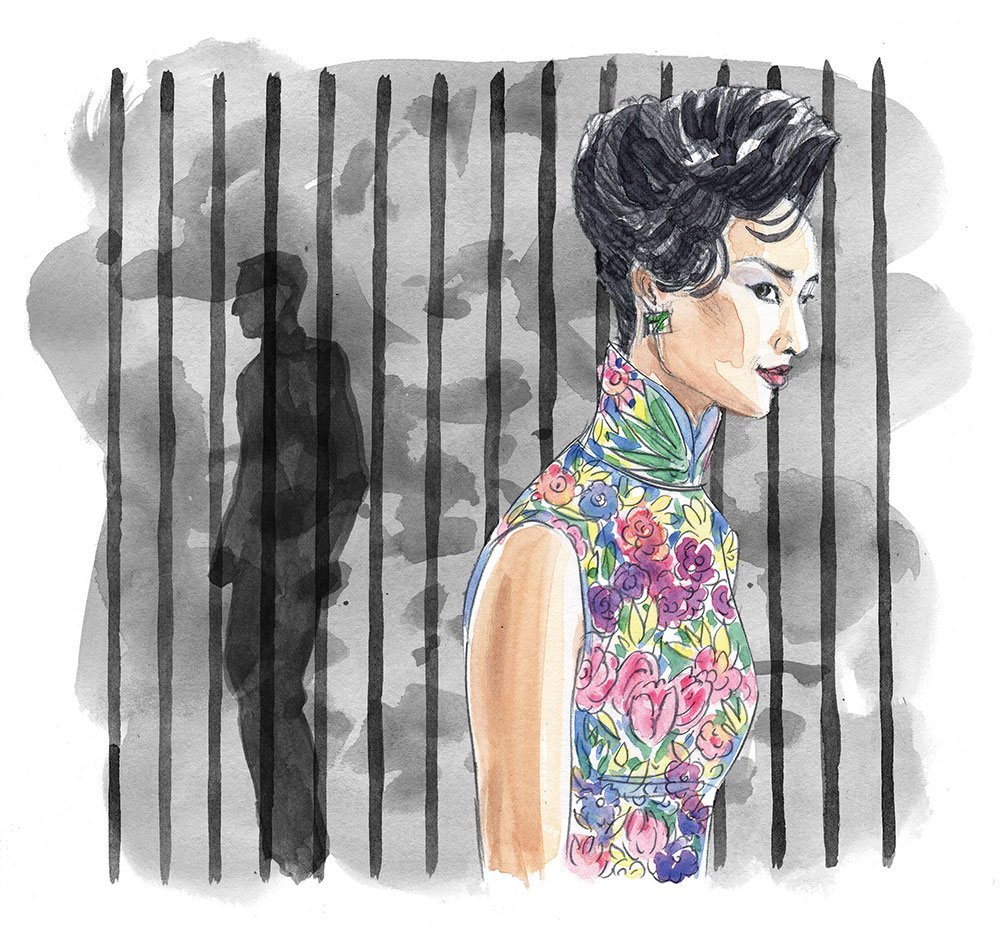

Technology and terror

In our latest issue of Mekong Review, our lead review is a look at two new books on Xinjiang. There, the PRC’s surveillance system has reached a terrifying apex as authorities seek to detain, control and ultimately break the Muslim population.

‘Big data and AI are facilitating the eradication of Uyghur culture and life in a digital genocide,’ writes Robert Templer. ‘This time they are not being eliminated, but their culture is being erased and they are being forced into factory work against their will. Constant observation by a modern panopticon forces complete compliance, breaking the spirit as much as the abuses inside the new gulag.’

In the Camps: China’s High-Tech Penal Colony, by anthropologist Darren Byler, and The Perfect Police State: An Undercover Odyssey into China’s Terrifying Surveillance Dystopia of the Future, by journalist Geoffrey Cain provide a deep, disturbing view of what life looks like in this system. We spoke with Byler, an Assistant Professor of International Studies at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, about his findings, and the implications for other nations.

You note throughout the book that abuse of ethnic minorities, an overzealous war on terror, the role played by powerful economic interests, and even the use of predictive policing is hardly unique to China. Are the horrors we see in Xinjiang, then, simply a matter of scale? Or is there a fundamental difference in China’s approach?

What is happening in Xinjiang borrows basic technologies and counter-terrorism strategy from other places. Deeply problematic ‘countering violent extremism’ or CVE programs in North America and Europe ostensibly are focused on preventing people, particularly Muslims, from being radicalised by placing them on watchlists and in some cases detaining them. And the use of face recognition and dataveillance is something that civil rights advocates decry in many places.

What is different in China is the scale and more specific tactics that are used. These aspects are interrelated. The Chinese government has spent around $100 billion dollars to build the systems of the Muslim re-education campaign, which is remarkable, but as part of this system they have also hired around 90,000 low level government contractors to maintain the system. These workers are paid only around $300-400 a month. They have also mobilised 1.1 million mostly Han ‘volunteers’ to monitor the families of detainees and others on watchlists. This mass mobilisation of a ‘people’s war’ against terrorism is unique to China’s authoritarian context and the history of mass campaigns. The legal and carceral systems likewise build on older camp and re-education systems for ‘untrustworthy’ populations that were instituted during the Maoist period.

Many of the survivors you feature in your book are urban, secular, educated, and Chinese-speaking. And some, such as a police contractor and a teacher, are both victims and perpetrators. Was that a deliberate choice on your part?

I chose the figures I did in the book in part because they were in safe places and able to speak to me. In order to escape the region, it is very beneficial to have economic mobility and knowledge of Chinese. However, among the Kazakh former detainees I interviewed, significant numbers of them were also rural herders with very limited knowledge of Chinese. Adilbek, one of the former detainees who speaks from the position in the book, evoked such powerful images of social death and dehumanisation—of preparing a sheep for slaughter and the way shepherds strike their sheep—that it was hard not to shed a few tears with him. In order to convey a sense of the inarticulable yet looming presence of the system, it was important to choose figures who could narrate it from different class, gender, ethnic, political and geographic positions. Rather than pointing to the easier targets of central leaders, I also wanted to show how a ‘swarm of functionaries,’ as Primo Levi might refer to them, were pulled into the system as low-level perpetrators.

Given the increasing popularity of this type of biometric surveillance across the globe, do you see the situation in Xinjiang as a harbinger for other nations?

The possibility of this is certainly something that should trouble anyone with an interest in racial justice and decolonisation. I’m particularly concerned about the development of such systems in places like Hong Kong, Kashmir and Palestine. However, it is also important to be clear that implementing a system like the one in Xinjiang takes a great deal of money, an army of low-level technicians and an authoritarian government with the political will to colonise an entire population of people without regard for international law. Without those elements in place, it will be difficult for other nations to target minorities in the same way.

From the archives

That era

Wong Yi

The smartphone ad on the exterior of the building read: THAT ERA HAS PASSED. NOTHING THAT BELONGED TO IT EXISTS ANYMORE. Did the company have to pay royalties to Wong Kar-wai or Liu Yichang? Mrs Chan wondered. In an ad quoting a literary work that is better known for being quoted in a film, who should pay royalties to whom? Had the ad agency and their client given this question as much thought as she had? But surely this multinational smartphone company, which had more loyal followers than any government or religion in the world, wouldn’t make such a careless mistake.

Era, era. While waiting to cross the street, she noticed that some of the graffiti on the pavement and walls had been covered up with various kinds of grey paint, but the outline of the word ‘era’ was still faintly visible in some places. Even her aunt, who’d been on her case to have a baby early on, said that Hong Kong was such a mess now that it would be best for her to get out if possible. Her aunt was the sort of traditional woman who always spouted off maxims such as ‘Couples’ quarrels are soon mended’ and ‘All problems can be talked through’. Perhaps she’d decided to go to America to help raise her grandkids, which also was in keeping with her character: in order to be considered safe and secure, a woman should follow her husband, or her children and grandchildren, forever defined by her womb and her man.

Read more here

See:

On 4 August, the Cambodian artist Srey Bandaul died at the age of 49 from COVID-19. Bandaul, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge who began his legendary arts school Phare Ponleu Selpak with arts classmates from the Site II refugee camp, was one of the seminal figures of Cambodia’s modern arts movement. Countless young Cambodian artists today trace their start to Phare and to the Battambang arts culture Bandaul helped cultivate. Read a moving obituary by Michelle Vachon here and watch a tribute video from Phare featuring Bandaul and his artworks here.

![]()

- Tags: Newsletter