Fukushima is oddly tidy for all that death that lurks in its forested hills and emerald-green river valleys. On 11 March 2011, or 3/11, as it is known in Japan, nearly 20,000 people were killed by a magnitude 9.0 earthquake and tsunami that wiped out entire towns and scrubbed the northeastern coast of Japan free of human habitation for up to ten kilometres inland. Even before the tsunami flooded six nuclear reactors at the Fukushima power plant, the Tohoku earthquake—the biggest recorded in modern Japanese history—had crippled the cooling system and sent the plant careening towards the meltdowns and explosions that would rock it over the next few days. One hundred and sixty thousand people were evacuated from a nuclear exclusion zone that kept growing, until parts of it, downwind of the reactors, stretched nearly 100 kilometres inland.

Nine years on, three of Fukushima’s reactors are still so radioactively hot that the robots sent to examine them are fried in minutes. Five thousand people labour daily to contain the ongoing disaster. They pump cooling water into reactor cores and fuel pools, while struggling to keep the damaged buildings from collapsing. More than a billion litres of contaminated water—the equivalent of 480 Olympic-sized swimming pools—are stored on site in rusting tanks. Another river of groundwater flows down from the mountains into the basements of the flooded reactors, where it becomes contaminated before leaking into the Pacific Ocean.

Ringing the power plant are the police check points that keep people from entering areas that will be radioactive for decades, if not centuries. Outside this nuclear exclusion zone labours another army of workers in white hazmat suits. Totalling 88,000 over the years, these are the nuclear gypsies, an itinerant labour force, often recruited by the Japanese mafia, who are hired to fill black vinyl garbage bags with topsoil scraped from school yards and other debris gathered from around people’s houses. This removes enough radioactive material to allow parts of Fukushima to be declared open for resettlement. The government has also redefined allowable levels of radiation exposure. In Fukushima prefecture, these levels are twenty times higher than any place else in the world, including the rest of Japan. The threshold for what qualifies as nuclear waste has also been raised. This is now eighty times higher.

‘The Japanese government has been aggressively pushing the lifting of restrictions orders for contaminated municipalities in Fukushima,’ says Tilman Ruff, co-founder of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, winner of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize. ‘This artificially reduces the number of officially recognised evacuees. While attempting to create a misleading illusion of return to normality, the government is still now, nine years after the disaster, applying an allowable radiation annual dose limit for the public of 20 millisieverts. It is the only government worldwide to accept such a high level so many years after a nuclear disaster.’

Before the 2020 Olympics were postponed by the coronavirus pandemic, the relay race marking the opening of the games was scheduled to begin at J-Village, the Japan Football Association Academy for training soccer players. J-Village lies nineteen kilometres south of Fukushima Daiichi. This is Fukushima Number 1, or FI, as the complex of six nuclear reactors was called, to distinguish it from Fukushima Daini, Fukushima Number 2, another complex of four nuclear reactors built ten kilometres from J-Village. J-Village housed atomic refugees from Fukushima and served as the command centre for managing the disaster. Now scrubbed of contaminated particles and soil, the site was supposed to showcase what organisers were calling Japan’s ‘Reconstruction Olympics’. From here would begin the relay race through the abandoned towns and rice paddies surrounding the Daini and Daiichi reactors. The torch would then head to Fukushima City, sixty-five kilometres to the northwest, where the first six Olympic Games in softball and baseball were to have been played.

Fukushima is ‘under control’, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo reassured the Olympic Committee in 2013. ‘Mr Abe’s “under control” remark was a lie,’ said former Japanese prime minister Junichiro Koizumi at a press conference in 2016. Since then, charges have escalated into claims that Japan bribed its way into securing the Olympics. The head of the Japanese Olympic Committee, who has since retired, is currently under indictment in France for buying the votes of African delegates with US$2 million laundered through a PR firm in Singapore. In the meantime, the cost of the 2020 games—even before the added expense of delaying them—had ballooned to US$26.4 billion.

In April 2019, Prime Minister Abe rode the bullet train from Tokyo to Koriyama City. From there he was driven in a motorcade to J-Village. According to his official schedule, the prime minister ‘interacted with elementary and junior high school students’ long enough to shoot some photos. From Japan’s football training camp, he drove nineteen kilometres north to the Fukushima power plant, where his car was waved through the gate and parked at the base of a viewing platform. Abe mounted the platform and positioned himself in front of Fukushima’s reactors long enough for another photo op. He would later describe how safe Fukushima was, because on this, his third visit to the power plant, instead of wearing protective clothing and a face mask, he was dressed in a suit and tie. Abe’s visit to Fukushima lasted six minutes.

As radiation continues to leak from Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean and surrounding countryside, perhaps 100,000 people are still displaced from their homes. The area remains an officially designated nuclear exclusion zone, but the Japanese government stopped paying housing subsidies to evacuees in 2017. This is part of an effort to force people back into their abandoned towns. As the UN special rapporteur noted in 2018, ‘The gradual lifting of evacuation orders has created enormous strains on people whose lives have already been affected by the worst nuclear disaster in this century. Many feel they are being forced to return to areas that are unsafe, including those with radiation levels above what the government previously considered safe.’ With most of Fukushima’s refugees reclassified as ‘voluntary evacuees’, the Japanese government claims that only 41,112 people remain displaced.

Japan is conducting a risky experiment with its citizens. The contest involves learning how to survive in an irradiated landscape. Citizen scientists, women’s collectives and support groups with ties to Chernobyl and other nuclear exclusion zones have formed to meet the challenge. They are building home-made radiation detectors, developing radiation-resistant crops, sharing news online, filing court cases and exchanging information around the world.

‘The government, on the grounds that an emergency situation prevails, has scrapped the usual regulations and abandoned several million people to live in contaminated areas,’ says Koide Hiroaki, a nuclear physicist who has been a fierce critic of Japan’s ‘nuclear village’—the term used to describe the country’s pro-nuclear lobbyists and officials. ‘Staying in contaminated areas hurts the body, but evacuation crushes the soul. These abandoned people have been living in anguish every day for eight years,’ he says.

Refugees from the Fukushima disaster were resettled in prefab encampments erected in parking lots and fields at the edges of inland cities away from the coast. The camps have been emptying since the government cut off aid to evacuees in 2017, but few people have returned to their old homes in the exclusion zone, which today is filled with ghost towns, abandoned store fronts, collapsing houses, vine-covered cars and wild animals nesting in the urban ruins.

Given the government’s desire to resettle the area as rapidly as possible, it is not hard to visit Fukushima. The bullet train north from Tokyo to Iwaki takes about four hours. After picking up a rented car, paranoid visitors worried about eating local food can drop into the market in the basement of Iwaki’s biggest department store and stock up on rice balls and water. From there one drives north over a range of mountains, before dropping down into what were once the green paddy fields and pastureland of coastal Fukushima. The first hint that one is entering a disaster zone comes when the road crests the mountains. The big green signs along the highway, instead of indicating exits and local attractions, give LED readouts for the amount of caesium-137 and other gamma radiation blowing up from the coast. The numbers fluctuate with activity at the power plant and the prevailing winds, but one is advised to travel these roads as rapidly as possible, with the windows closed.

Far in the distance, one catches a glimpse of the ruined power plant. Crouched near the water on a shelf carved from a rocky headland, Fukushima Daiichi’s six reactors and eight fuel storage pools are covered with construction cranes that look like praying mantises feeding on a delectable carcass. A line of grey steel towers runs from the plant up into the hills and south towards Tokyo, which used to light itself with energy from Fukushima. Thrown over the pylons is a black net of power lines that no longer carry power. This was once a mystical place, where atoms were split to light up the night sky in Tokyo. Now it looks like the hulking wreck of a ruined civilisation.

Running north and south from Fukushima are the concrete seawalls that Japan built after the tsunami to protect itself from future earthquakes and shock waves. The walls stretch intermittently for 480 kilometres along the eastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island. Nine metres high, the walls look like runways in an empty airport. Down at water level, the massive revetments block the horizon behind a grey scrim of concrete. The walls are positioned against an invasion, but the invader, in this case, is the ocean from which Japan gets much of its food. On a coastline often lashed by tsunamis and typhoons, where the Japanese used to look out to sea and read the waves for signs of danger, now they hunker behind concrete walls that have failed to protect them in the past and that are likely to fail again in the future.

Dropping down into the plain surrounding the power plant, one senses that something horrible has happened here. The land has been swept clear of houses, schools, towns, harbours. The wave that doomed Fukushima Daiichi also drowned people and animals, before sucking their bodies out to sea. Some towns were destroyed completely. Others look like gap‑toothed survivors that are missing some but not all of their buildings. What the tsunami did not destroy was subsequently doomed by the radioactive fallout from Fukushima. The forced evacuations and the toxic clouds that still waft up into the hills have left the scrubbed plain and towns eerily quiet. No one is working the fields. No one is herding animals or sailing fishing boats out to sea. No one is driving to town for groceries or picking up children from school.

The only signs of activity come from trucks rolling through the countryside. They are carrying black vinyl bags full of irradiated refuse that is being dumped in the former rice paddies and fields of Fukushima. Mountains of debris have been scraped up by workers, many recruited from Vietnam and the Philippines, who travel through the abandoned towns around Fukushima like white-suited locusts, removing topsoil, saplings, brush, bark and other radioactive material from areas being readied for resettlement. The flat-topped pyramids of toxic waste are a temporary solution, says the government, which is offering a large sum of money to any community willing to build a permanent repository. So far there are no takers.

Yuki and Eri, my two research assistants, and I drive past a field full of men in hazmat suits. They are scraping five centimetres of topsoil off a pasture whose red clay now looks like a nasty wound. Down at sea level, with a concrete wall looming over us, we thread our way through a construction site where workers are building a white fence around a towering pile of one-tonne vinyl bags. The country opens into scrubby fields swept free of habitation, save for a couple of houses that look like something remaining after a tank battle in Flanders. The windows are blown out. Mouldy shoes are stored on racks inside door frames with no doors. All the furniture is gone, except for one house with a piano upended in what used to be the living room. In front of a three-storey building that was once a school, we come on a strange sight, a half dozen oversized frogs, cast in concrete, that are lined up like sentinels. Rising over the building, on the seaward side, is a tower that served as a lookout for scanning the horizon. Because their teachers saw the wave coming and led everyone to high ground, the children in this school were saved.

Farther south along the coast rises a little hill with stone steps leading up to a Shinto shrine. The shrine survived the tsunami, but its stones are cracked and heaved. Moss grows in the votive niches. The coast was once covered with pilgrimage sites. The most curious of these are the stone markers placed on the hillsides. Dating back hundreds of years, the stones are carved with inscriptions that warn about tsunamis. The stones are time travellers, speaking through the ages, saying, ‘Beware! The ocean has come this high and destroyed everything in its path. Whatever you build below this marker, it too will be destroyed.’

Still farther along the coast one finds another strange sight, a windowless, four-storey building with a chimney poking out of the roof. This is one of the incinerators that Japan has built every few miles up and down the coast. One reason why the countryside looks so empty is because workers have been collecting all the ruined houses and boats, the furniture and flotsam that was scattered over the landscape and burning it, regardless of how toxic it is, so that now the ash in these incinerators is a concentrated mass of radioactive material. This has not stopped Japan from allowing the ash to be used in construction projects, which is one reason why people have recorded dangerous levels of radiation at building sites throughout the country.

We drive into Namie, a once-thriving city of 20,000. Namie is now a ghost town of abandoned buildings and traffic lights blinking over empty boulevards. Eight kilometres north of the power plant, the city lies within Fukushima’s original twenty-kilometre exclusion zone, which was evacuated soon after the plant began releasing plutonium, caesium, iodine-131 and other radioactive substances. The houses in Namie are beginning to fall into the ground. Their roofs are covered with white splotches where the tiles have blown off. The cars parked out front are overgrown with vines and creepers. The yards are untended, with perennials poking up through the weeds. Other yards, closer to the centre of the city, have been scraped of topsoil. Here the houses have been power-washed and left standing on what look like clay tennis courts. A fishing boat leans against an abandoned bowling alley. The car dealers downtown have showrooms stocked with radioactive cars. The clothing stores are displaying sun dresses and chinos that were in style nine years ago. The grocery stores are filled with food dumped off the shelves during the earthquake and aftershocks. The hospital is a looming hulk with locked doors and weeds growing in the parking lot. The schoolyards have been scraped of topsoil, but no children have returned to play in them.

Scattered throughout the town are metal posts, topped with LED readouts showing the amount of gamma radiation blowing through the air. On days when the readings are high, with the wind blowing directly from Fukushima Daiichi, people are supposed to stay indoors with the windows shut. Three thousand six hundred radiation monitoring devices have been installed in the towns and up in the hills behind the reactors. The devices read low, people say, measuring one-half to one-third what is recorded by their personal devices. Critics also say the posts are spaced too far apart, missing the hot spots where radiation can spike to alarming levels. The monitoring posts are one of the few remaining signs of an ongoing nuclear disaster, but the Japanese government is in the process of removing them.

The posts measure ionising radiation emitted primarily by caesium-137, a radioactive element that was first observed on Earth in 1945, after the first atomic bomb was exploded in New Mexico’s Jornada del Muerto desert. The four types of radiation—alpha, beta, gamma and neutron—are invisible forms of matter that destroy human tissue. They are distinguished by their levels of energy and ability to penetrate solid objects. Gamma rays enter our bodies and alter genetic material by ionising, or removing electrons from atoms. Living cells that are ionised will die, mutate or become cancerous. Hardest hit by ionising radiation are cells that are rapidly reproducing, such as those in a growing foetus. While gamma rays can travel through matter easily, destroying bone marrow and internal organs, alpha particles are blocked by clothing (although lethal if ingested). Beta particles are blocked by thin sheets of metal or plastic. Gamma rays are stopped by nothing short of lead shields or concrete barriers. Neutron rays, which are released during the fission process in nuclear reactors, are large radioactive particles that can travel many miles and pass through everything, including concrete and steel.

Ionising radiation enters our bodies and food chain in a variety of ways, and, thanks to a process called bioaccumulation, the higher an animal eats on the food chain, the higher the concentration of radionuclides. The effective dose of radiation required to sicken or kill you is measured in sieverts (Sv), which is named after Rolf Sievert, the Swedish physicist who first calibrated the lethal effects of radioactive energy. A burst dose of 0.75 Sv will produce nausea and a weakened immune system. A dose of 10 Sv will kill you. A dose somewhere in between gives you a fifty-fifty chance of dying within thirty days. Guidelines for workers in the nuclear industry limit the maximum yearly dose to 0.05 Sv or the equivalent of five CT scans. So how many sieverts are currently being produced by Fukushima’s melted reactors? The latest reading from reactor No. 2 is 530 Sv per hour. This means that every hour the reactor is emitting more than 10,000 times the yearly allowable dose for radiation workers. With reactors this hot, Japan’s plan to scoop up Fukushima’s nuclear fuel and dump it somewhere, which is projected to take forty years, may not be possible. In this case, Fukushima, like Chernobyl, will have to be entombed in three giant pyramids of concrete, which will be Japan’s legacy to the archaeologists of the Anthropocene.

Measuring gamma radiation is useful, particularly on days when the radiation climbs to dangerous levels, but these measurements are by no means a complete picture of Fukushima’s toxicity. For this one needs soil samples, mass spectrometers, electron microscopes, radiographic imaging and other sophisticated equipment. Radioactive isotopes from Fukushima, including caesium-134/137, have been wafted around the world, with substantial levels found in California vineyards, Pacific Ocean currents and even in people’s homes and everyday objects. In 2013, microparticles from Fukushima—little glassy beads loaded with radioactive caesium and uranium—were discovered in Japan when scientists began collecting vacuum cleaner bags and automobile air filters. These bags and filters, when laid on top of x-ray plates, lit them up with radioactive hot spots. The hot spots were bacterium-sized particles that had been shot out of exploding reactors and travelled over Honshu Island down to Tokyo and beyond.

Fukushima prefecture is full of hot spots, and these hot spots keep moving as microparticles are washed down from the mountains. A recent discovery by Shaun Burnie, a senior researcher with Greenpeace, who has directed radiation surveys in Fukushima since 2011, shows how dangerous the area remains. Burnie uses drones and high-tech sensors mounted on cars, but on a crisp fall day in October 2019 he decided to take a handheld radiation detector and pay a visit to J-Village. Burnie was in the parking lot, watching a youth soccer match being played on the field and walking towards another group of children who were sitting on the tarmac eating their lunch, when he began measuring radiation levels over 71 microsieverts per hour. The normal reading in this area, before the Fukushima meltdown, was 0.04 microsieverts per hour. Burnie’s reading, 1,775 times higher than normal, meant that anyone breathing dust off the J-Village playing fields could have been inhaling an intensely charged radioactive particle.

‘This is one of the most shocking discoveries I’ve made in decades of radiation surveys,’ Burnie says. The place was crowded with ‘sports fans, family members, and coaches’ strolling through what was effectively a toxic waste dump. Greenpeace wrote a letter alerting the Japanese government to ‘high levels of radioactive contamination and serious public health risks at J-Village’. Getting no reply, Burnie announced his discovery at a press conference in December. Tokyo Electric sent workers to clean up the area, but Burnie returned to find other hot spots they had missed. The Japanese government continues to claim that there are no radiation risks in Fukushima. ‘With the exception of areas deemed “difficult to return”, ’ says Reconstruction Minister Watanabe Hiromachi, using Japan’s polite expression for nuclear exclusion zones, ‘we have decontaminated the entire area’.

Officials say that Fukushima is safe because the level of background radiation in the surrounding environment is no higher than in New York City or Shanghai. This may be true, but, again, one is referring only to gamma radiation, and the argument is deceptive for other reasons. The confusion is due partly to the fact that Fukushima refers to three different things: a destroyed nuclear power plant, a prefecture more than twice the size of greater Shanghai and a capital city. Ignoring microparticles, hot spots, glowing reactors, toxic wastewater and other inconvenient facts, the Japanese government measures the background radiation for ‘Fukushima’ by averaging the readings from all the gamma radiation detectors placed outside the nuclear exclusion zone.

One should also note that the background radiation for New York City includes not only the cosmic radiation that rains down on Earth from the heavens or trickles up from radioactive rocks, but also the residue from 520 nuclear bombs that were exploded mid-air during the Cold War, mainly by the United States and Soviet Union, but also by France and China, whose last bomb exploded in 1980. Altogether, including bombs fired underground, 2,056 nuclear weapons have been detonated. In other words, background radiation is not necessarily a natural phenomenon, nor is it necessarily good for you.

If Rolf Sievert got his name on the unit for measuring the health effects of radiation, it was Henri Becquerel, co-winner of the Nobel Prize with Pierre and Marie Curie, who got his name on the unit for measuring total radioactive releases. The Promethean splitting of atoms produces radioactive disintegrations known as hits. One hit is one becquerel, and each hit can cause damage or disease. The current benchmark for nuclear disasters is the 1986 explosion at Chernobyl’s reactor No. 4, which released 85 quadrillion becquerels of caesium-137.

Nobody knows the comparable numbers for Fukushima, since most of its radioactivity was dumped into the Pacific Ocean. At the high end, Fukushima released twice as much radioactivity as Chernobyl. At the low end, the release was one-fifth of Chernobyl’s. But if 85 quadrillion becquerels sounds like a large number—and indeed it is—this is only one-tenth the amount of caesium released by nuclear bombs, which lofted a staggering 954 quadrillion becquerels of caesium into the atmosphere and marked the onset of the geological era known as the Anthropocene.

Another misunderstanding underlies the claim that Fukushima’s background radiation is safe. The background radiation in New York consists of rays or photons that pass through the body and leave. The radionuclides from Fukushima are not rays, but dust-like particles that if inhaled or ingested can prove lethal. Throughout the area, radionuclides of caesium-137 have accumulated in ditches, drainage areas, kitchen gardens and schoolyards. One can walk a few steps in any direction from a safe area and stumble into a hot spot. This is what a researcher found when he examined the Azuma baseball field in Fukushima City, where the Olympic games were scheduled to start. The field had been scraped clean, but just outside the stadium were patches of grass radioactive enough to qualify as a nuclear waste site.

Seventy per cent of Fukushima consists of forests and mountains. This reservoir of radionuclides cannot be decontaminated. In the lowlands, the vinyl bags holding scraped-up topsoil have begun to break apart with sprouting vegetation, and every summer, as typhoons lash Japan’s eastern shore, dozens of bags are washed out to sea. Scraping off five centimetres of soil lowers radiation levels, but it is not correct to call this ‘decontamination’. The process is more about managing people’s perception of radiation than it is a solution. Caesium-137 and strontium-90 persist in the environment for hundreds of years, and this radiation is not being recycled or eliminated. It is merely being moved from one place to another, and it will keep moving with the area’s winds and rains and ocean currents.

The Japanese government is taking other steps to hide the ongoing disaster. A government-sponsored study of radiation exposure outside the nuclear exclusion zone undercounted people’s exposure by two-thirds. Doctors have left the area because the government refuses to reimburse them when they list radiation sickness as the cause for nose bleeds, spontaneous abortions and other ailments resulting from ionising radiation. (The only acceptable diagnoses are ‘radiophobia’, nervousness and stress.) The spike in thyroid cancer among children in Fukushima is dismissed as a survey error, produced only because more children are being examined. The government has mounted no epidemiological study in Fukushima. It has established no baseline for comparing public health before and after the disaster, and as radioactive ash and soil from Fukushima are spread throughout the rest of Japan, detecting the long-term consequences of the disaster becomes increasingly difficult.

It is in Namie that I experience my first direct encounter with radioactivity. As I get out of the car to photograph the bowling alley with the boat leaned against it, there is a metallic taste in my mouth, a lick of gunmetal. People undergoing radiation therapy experience the same metallic taste; so, too, did the pilots who dropped the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As we head down National Route 6 towards Fukushima Daiichi, road signs instruct us not to stop or get out of our car, and we drive with the windows shut. This highway is kept open for the construction vehicles that carry workers to the power plant. We wedge our car into a stream of truck traffic and roll towards the electric cables that run up the mountains towards Tokyo. The auxiliary roads to our left and right are closed with accordion fences and guarded by men in blue uniforms. The men wear white gloves and cotton face masks, which offer scant protection against the swirling dust and contaminated air.

We stop on a bluff overlooking the ocean. Below us, down on the shoreline, rise the big square boxes of Fukushima’s six reactors. We are parked on the alluvial terrace that was cut away to build the power plant. This was the fatal mistake that doomed Fukushima from the beginning. General Electric, which prepared the site and built the reactors, lopped twenty-five metres off a natural promontory to put the power plant near the shore. This required less pumping of cooling water. It was cheaper. The plant was built eleven metres above the ocean, with a three-metre seawall. Later enlarged to six metres, this wall was easily overtopped by the fifteen-metre wave that washed over Fukushima on 3/11.

Locating cooling pumps at the ocean’s edge and backup generators down in the basement were other mistakes. So too was buying GE’s Mark 1 reactors. These were known to have design flaws and inadequate containments. Fuel storage pools covered with flimsy metal roofs were built on top of the reactors, and when one of these pools exploded at reactor No. 4, a fresh nuclear core and another three reactors’ worth of nuclear fuel were exposed to the sky. Save for a valve leaking from a nearby reservoir, the pool would have run out of water, ignited a fuel pool fire and forced the evacuation of Tokyo as a massive radioactive cloud billowed from Fukushima down to the Imperial Palace, which lies 225 kilometres south of the reactors.

We stare for a few minutes at the cranes swinging over the plant. They are shoring up the damaged buildings, installing temporary tanks for holding contaminated cooling water and offloading fuel from a storage pool in one of the reactor buildings. Workers in hazmat suits are welding pipes and driving earth-moving equipment through a construction site that looks like the set for a sci-fi movie. This could be an operating room for giants, where ten-storey scalpels probe the exposed organs of a dangerous creature—maybe Godzilla—born of atomic radiation and raging for revenge. This is no place to linger. Our dosimeters are spiking, and the metallic taste in my mouth is getting stronger as we turn around and head back up the coast.

That must be admitted—very painfully—is that this was a disaster “Made in Japan”, ’ concluded the official parliamentary report on Fukushima. The disaster resulted from the ‘ingrained conventions of Japanese culture’. This includes deference to powerful interests, including TEPCO, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, which owns the Fukushima reactors. TEPCO ranks among the least trusted companies in Japan. It has been fined on several occasions for false reporting on inspections and repairs. In 2002, one of these scandals forced the resignations of TEPCO’s president and chairman. Fukushima was a ‘man-made disaster’, said the investigating commission, because the power plant’s design was faulty, its seawall defences were known to be inadequate, and the company proved incompetent in handling the crisis.

‘Across the board, the commission found ignorance and arrogance unforgivable for anyone or any organization that deals with nuclear power,’ the report concluded. ‘We found a disregard for global trends and a disregard for public safety.’

Critics say that leaving TEPCO in charge of containing the Fukushima disaster is like asking the local power company to launch a space station. TEPCO has confessed to misleading the public about the amount of radiation leaking from the plant and the progress of the clean-up. It keeps delaying the start for emptying Fukushima’s fuel pools, its strategy for dismantling the reactors is fundamentally flawed, and it has failed at even the most straightforward technological challenges, such as containing the radioactive groundwater flowing from the reactors.

The public learned these facts when the secret testimony of Fukushima plant manager Masao Yoshida was revealed by Asahi Shimbun newspaper. Before his death of cancer of the oesophagus in 2013, at the age of fifty-eight, Yoshida had been summoned to the J-Village soccer training camp for twenty-eight hours of interviews with Japan’s parliamentary investigating committee. Showing obvious disdain for both his TEPCO bosses and Japan’s nuclear regulators, Yoshida described an alarming train of events, many of them at odds with the official story of what happened at Fukushima.

At 2:46 p.m. on 11 March 2011, the day Fukushima was destroyed, Yoshida was sitting in his office on the second floor of the business building in the centre of the site. He was looking at documents when the building began to shake with enough intensity that binders fell from the shelves and a TV set toppled over. Yoshida tried to dive under his desk but failed. The ground heaved under him for five minutes as the Tohoku earthquake tore a trench in the ocean floor 370 kilometres to the northeast. The quake was so massive that it shifted the coast of Japan 2.4 metres closer to the United States and knocked the Earth 38 centimetres off centre, thereby shortening the length of the average day by 1.8 microseconds. Forty-one minutes later, a wall of water travelling at the speed of sound slammed into Japan’s northeastern coast, destroying everything in its path as it rolled inland. Among the victims were close to 20,000 people either killed or missing and a power plant whose backup generators and cooling pumps had been built below sea level.

When Yoshida was able to walk next door to the general office, he found a ceiling panel collapsed in the middle of the room. Documents were scattered over the floor, and white dust floated in the air. Even before the tsunami arrived, he knew the plant was in trouble. The site had lost electric power. Pressure gauges showed damage to the reactors’ cooling pipes. The isolation condenser in Unit 1 had failed. The reactor was no longer being cooled, and Yoshida feared it was heading towards the meltdown and runaway chain reaction that would eventually blow it up. That the reactor was already emitting hot radioactive gases from its core was confirmed by monitors outside the plant, which had begun recording releases approaching 12 millisieverts per hour.

Yoshida launched himself into a mad scramble to contain the disaster. He rode out the aftershocks from the earthquake and watched in horror as the tsunami struck the plant. The wave flooded the diesel generators that were temporarily powering the facility. Standing in a dark office filled with dead computers, Yoshida ordered workers into the parking lots to salvage batteries from flooded cars. When this jerry-rigged system failed to operate the control valves and restart the cooling pumps, he formed ‘a suicide squad of oldies’ and rushed them into the reactor buildings. Facing lethal waves of radiation as they scrambled in the dark over waterlogged wreckage, the workers tried to force open valves with their bare hands. Known as the Fukushima Fifty (although they actually numbered sixty-nine, including Yoshida), the suicide squad stumbled through reactor buildings filled with a thick white mist of hydrogen and water vapour.

The dose limit for Fukushima’s workers was raised from 1 millisievert, the level for the general populace, and 20 millisieverts, the level for nuclear workers, to 100 millisieverts, and then, on 14 March, it was raised again to 250 millisieverts. This is five times the US legal limit for nuclear workers, but since most of the plant’s dosimeters had been destroyed by the earthquake or washed away by the tsunami, no one knows how much radiation these men received. The official death toll for Fukushima workers from cancers linked to the disaster currently stands at six, according to Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Masao Yoshida is not included in this count.

Yoshida called TEPCO headquarters and asked that fire engines big enough to pump water into the reactors be sent from Tokyo. The tsunami had destroyed roads and towns along the coast. The fire engines got lost. They suffered flat tyres and ran out of petrol. At one surreal moment TEPCO announced that it was running out of cash and asked for donations from the public. Suspecting that the company was lying to him about the severity of the disaster, Naoto Kan, Japan’s prime minister, helicoptered into Fukushima for a meeting with Yoshida at 6:00 a.m. on the morning of 12 March. Both men were engineers who had graduated from the Tokyo Institute of Technology. Kan was a mechanical, not a nuclear, engineer, but he had already discovered that the head of Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) was an economist who knew very little about nuclear energy and nothing about nuclear accidents. The same was true for the other members of Japan’s ‘nuclear village’, the powerful network of vested interests that had ringed Japan’s earthquake-prone shores with nuclear reactors.

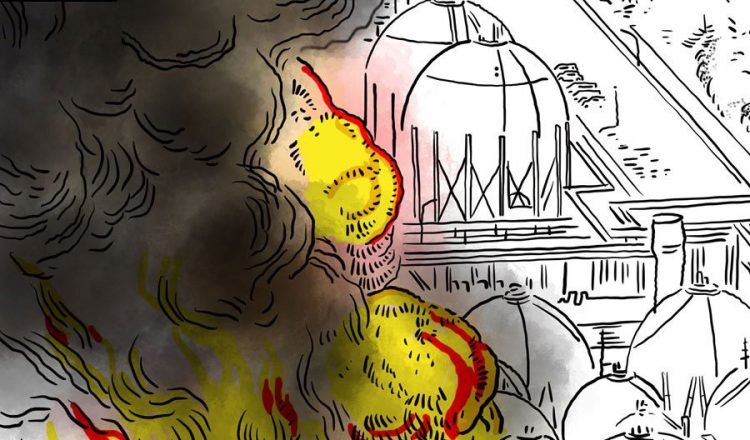

At 3:56 p.m. on 12 March, a little more than twenty-five hours after the Tohoku earthquake, reactor No. 1 exploded in a fireball of hydrogen gas that blew out the roof and walls and began spreading radioactive material across the Pacific. As they watched the news bulletin on TV, Kan turned to the NISA chairman who was in the room with him and asked, ‘What was that just now? Wasn’t that an explosion?’ The chairman had both hands over his face. He made no reply.

At the time, TEPCO’s chairman was in China on a press junket. He was touring the reporters assigned to cover the nuclear industry on an Asian holiday. The president of TEPCO was also out of town, and, with no one ordering employees to release information to the prime minister, Kan was kept in the dark about what was happening at Fukushima. Like other advanced industrial countries, Japan is covered with radiation detectors that feed into a centralised monitoring system. The system is supposed to track wind currents and steer refugees away from contaminated areas. For most of the disaster, the wind was blowing out to sea—a lucky break for the citizens of Tokyo—but when the wind swung inland, blowing to the northwest, a radioactive cloud swept over refugees fleeing in that direction. None of this information was delivered to Kan.

The prime minister received another rude surprise when he learned that Fukushima No. 1 had been built by General Electric and installed in 1971 as a turnkey operation—as in, ‘Here’s the key to your nuclear power plant. Turn it on.’ Because the operating manual for the reactor belonged to GE, TEPCO refused to give it to the government. Even when the manual was later released to the Japanese parliament, GE’s intellectual property rights were protected by having parts of the manual blacked out.

While he was dealing with the explosion at reactor No. 1, Yoshida noticed that the cooling water in reactor No. 3 was dropping precipitously. Only belatedly did he realise that the fresh water source he had been instructed to use had dried up. Hydrogen had to be vented from the reactor or it, too, would explode. Hydrogen can be vented one of two ways, either from the bottom of the reactor, through water, which removes most of the radioactive iodine, or from the top, straight into the air. Having run out of water, Yoshida ordered that the reactor be dry-vented, but the operation was stopped by TEPCO officials in Tokyo, who feared they would be blamed for irradiating the Japanese countryside.

At 11:01 a.m. on the morning of 14 March, as a government spokesman was reassuring the public that everything at Fukushima was under control, reactor No. 3 exploded on live TV. The split screen image—government spokesman on one side, exploding reactor on the other—showed the power plant enveloped in a cloud of dust and gas that bore a terrifying resemblance to the mushroom cloud that billowed over Nagasaki in 1945. The resemblance was no mistake. Reactor No. 3 was a MOX reactor, running on mixed oxide fuel made from uranium and reprocessed plutonium. (The bomb dropped on Nagasaki had a plutonium core.) Japan has a huge stockpile of plutonium generated by its nuclear reactors. The country has spent billions of dollars trying to develop the technology to reprocess this plutonium. Several workers have been killed and the technology has yet to succeed, and here was the ultimate setback—a MOX reactor blowing up on live TV. The government responded by banning images of the explosion from television and joining TEPCO in forbidding use of the word meltdown.

While Japanese viewers were denied a second look, the rest of the world watched replays of reactor No. 3 exploding. Reactor fuel and parts of the reactor core itself are blown through the roof, leaving the spent fuel pool on top of the building exposed to the atmosphere. Billowing overhead is a black cloud of radioactive iodine, plutonium, caesium and other toxic gases. Mixed into this cloud are chunks of concrete and steel that fall back to earth, injuring eleven workers with flying debris. Out of the south-east corner of the reactor comes an intense pulse of radioactive gas. A slow-motion replay of the event reveals that a nuclear fission chain reaction has produced a detonation shock wave travelling at 900 metres per second, faster than the speed of sound. No nuclear power plant in the world can survive a detonation shock wave. Horrified spectators were watching radioactive gases flooding over Japan. They were also watching the myth of nuclear safety being blown sky high. As the Asahi Shimbun would later write about the government’s efforts to ban these images from TV, ‘In a nation where the government agency overseeing nuclear plants and electric power companies has no qualms about hiding crisis information, the situation can only be called hopeless’.

The following day, on 15 March, at 6:14 in the morning, reactor No. 2 exploded. It was the most heavily loaded of Fukushima’s reactors, with the freshest and largest load of radioactive fuel. Yoshida watched in horror as the reactor began melting through its containment vessel. ‘That penetration would have led to enormous amounts of highly toxic radioactive substances, such as plutonium, uranium and americium, spewing into the living environment of humans,’ he told investigators. ‘Plant workers would be exposed to huge doses of radiation.’ The Japanese were being torched by three atomic explosions—delivered not by an external enemy, but at their own hand. When the fire engine pouring water on reactor No. 2 ran out of diesel fuel, ‘This was when I thought we were coming to the end,’ said Yoshida. ‘I was the closest to death at that moment.’

Yoshida imagined he was watching a real-life version of The China Syndrome. Radioactive fuel was burning through its containment vessel and liquefying everything in its path as it burrowed towards the centre of the Earth. After it melted through the bottom of the reactor and hit water below, the nuclear core exploded. Steam rose from the damaged building and radiation levels at the power plant increased four-fold, indicating that the reactor’s suppression pool—the doughnut-shaped tube of water meant to cool the reactor in an emergency and capture any radioactive particles before they leaked into the atmosphere—had been breached.

Fourteen minutes before reactor No. 2 exploded, Prime Minister Kan had left his office and driven the short distance to TEPCO’s nearby headquarters. Kan, who had been living in his office, had learned at 3:00 a.m. that TEPCO was planning to evacuate its workers and abandon Fukushima Daiichi. ‘Abandonment would mean the end of Japan,’ Kan wrote in his post-Fukushima memoir, My Nuclear Nightmare. On entering TEPCO’s headquarters, he summoned the company’s executives into a conference room and in effect seized the company. ‘Abandonment is not an option,’ he told them. That would result in a disaster ‘two or three times the size of Chernobyl, equal to ten or twenty reactors’.

‘It would not be out of the question for a foreign country to come along and take our place,’ Kan said. When he was later criticised for this outburst, Kan redoubled his attack on ‘the closed nature and secrecy of the nuclear power industry, which was burdened by bureaucracy and monopolism in science … Throughout the entire system there reigned a spirit of servility, fawning, clannishness and persecution of independent thinkers, window dressing, and personal clan ties between leaders.’

Kan had already sketched a contingency plan for evacuating Tokyo and its 50 million inhabitants. While Japan was declaring a twenty-kilometre nuclear exclusion zone around the Fukushima power plant, the US military was instructing the100,000 soldiers and dependents at US military bases to evacuate from within eighty kilometres of the plant.

At 6:00 a.m. that morning, at the same time that reactor No. 2 was blowing up, reactor No. 4 exploded in a hydrogen fireball that blew off the roof and walls, leaving the spent fuel pool at the top of the building open to the sky. The reactor was down for maintenance, but its gas venting system was linked to reactor No. 3, which was producing enough flammable hydrogen to blow up both reactors. The core for unit No. 4, containing ninety tonnes of uranium, had been offloaded into the spent fuel pool. The pool already held 500 tonnes of fuel. In total, the fuel that was now on the verge of igniting in a runaway chain reaction contained 37 million curies of caesium-137—about ten times the amount released at Chernobyl. While a plume of radioactive smoke spread over Fukushima, another black plume was rising from the US embassy in Tokyo, which had begun burning sensitive documents and preparing to move south to Osaka.

The fuel pool at reactor No. 4 was four storeys above ground at the top of the building, where it was unshielded except for a metal roof. Water had to be pumped into the pool to keep it from igniting, but Fukushima no longer had any working generators or pumps. Emptied of water, fuel pools can catch fire in runaway nuclear chain reactions that produce intense pulses of gamma rays and neutrons. Since the world has yet to find a safe place for storing nuclear waste, most of this waste is stored on site. Crowded with nuclear assemblies that are packed closer and closer to each other, the average fuel storage pool holds the equivalent of six nuclear cores. Fukushima Daiichi had a total of six reactors, three of them shut down for maintenance, and seven spent fuel pools. Fukushima Daini, the newer plant to the south, had four reactors and an equal number of fuel pools. These ten nuclear reactors had a total capacity of 9,096 megawatts, making the plant almost two and a half times larger than Chernobyl. Now that the fuel storage pools were also at risk, the disaster had reached global proportions.

Yoshida gave orders to shelter in place and prepare to re-enter the damaged reactors. Instead, he watched dumbfounded as 650 employees commandeered company buses and fled down the coast towards Tokyo. This included all of Fukushima’s senior employees, including division managers and section chiefs, and all the officials from Japan’s nuclear regulatory agency. By 8:30 that morning, Yoshida—abandoned by everyone except his ‘suicide squad of oldies’—had begun the last-ditch effort to save Fukushima’s reactors from total annihilation.

His bosses at TEPCO headquarters had instructed Yoshida not to use saltwater for cooling the reactors. The salt would corrode the containment vessels and make the reactors unusable, and somehow TEPCO imagined restarting the reactors at a later date. Yoshida was still receiving instructions from his bosses not to cool the reactors with saltwater. He ignored them. He ordered the fire trucks to start pumping water from the ocean, as he desperately tried to cool the reactor cores before they melted through their containments and exploded. At the same time, for fear of alarming the public, the Japanese government was refusing to distribute stable iodine tablets, which block radiation from being absorbed by thyroid glands.

Naoto Kan was forced to resign in August 2011. His government had made too many mistakes in handling the disaster. Before leaving office, he tried to pre-empt Japan’s nuclear village by shutting down the country’s fifty-four nuclear reactors. It is Japan’s ironic fate—and the root of its current crisis—that Kan was replaced as prime minister by Abe Shinzo, a military hawk and nuclear booster, who is moving to restart Japan’s nuclear reactors and convince the world that Fukushima is open to resettlement.

With J-Village freshly repainted, Japan may be ready for the Olympics in 2021, but it is not ready for the world to look too closely at the perilous state of its nuclear affairs. TEPCO is planning to release its billion litres of contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean as soon as the games are over. For years, the company maintained that this water had been cleaned of radioactivity, save for tritium, which is water soluble and thereby impossible to remove. In September 2018, TEPCO was forced to admit that its cleaning process had failed, and the water is actually contaminated with high levels of strontium-90 and other radioactive elements. Japan’s fishing industry opposes releasing the water, and so too do Korea, China and other countries that still ban the importation of food from Japan.

Fukushima’s storage tanks, originally intended as a short-term solution, are built out of cheap steel, which has begun to corrode and leak. An Olympic-sized swimming pool of contaminated water is added to the site every week. It is no consolation that TEPCO has finally acknowledged what critics have said for years. The water is still radioactive—at levels up to 20,000 times higher than allowable safety standards—and TEPCO has no idea what to do with it.

From the day it opened, Fukushima Daiichi struggled to contain the groundwater that rushed down from the nearby mountains and flowed through the plant. Fukushima today is a swamp of groundwater and cooling water contaminated with strontium, tritium, caesium and other radioactive particles. Engineers have laced the site with ditches, dams, sump pumps and drains. In 2014, TEPCO was given US$292 million in public funds to ring Fukushima with an underground ice wall—a supposedly impermeable barrier of frozen soil. This has had ‘limited, if any effect’, says Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority, which is advising TEPCO to write off its high-tech failure and get back to pumping out the water.

In 2017, the Japan Institute for Economic Research estimated that the cost of cleaning up the plant and compensating people for their lost homes and livelihood could reach US$628 billion. Today, the cost is ticking close to a trillion dollars, about one-fifth of Japan’s entire economy, making this the most expensive industrial accident in history.

Japan has no tradition of investigative reporting. Instead, Japanese media rely on kisha clubs: reporting pools organised by big companies and government agencies. Even this limited reporting was hobbled in 2013 when Japan adopted a law protecting ‘specially designated secrets’. Whistleblowers, journalists and bloggers who obtain information ‘illegally’ face up to ten years in prison. Japan, which used to rank near the top of the World Press Freedom Index, by 2016 had fallen to seventy-second place.

‘A nuclear accident could cause the entire country to stop functioning,’ said Kan, after becoming an ardent opponent of nuclear energy. Japan is the least likely place in the world to find an energy grid powered by nuclear reactors. Atomic bombs killed hundreds of thousands of Japanese in World War II. In 1954, a Japanese fishing boat was accidentally irradiated by a hydrogen bomb exploded over Bikini atoll. Japan is rocked by more than 1,000 earthquakes a year and whipped by typhoons that roar over its islands every summer and autumn. The country has a large anti-nuclear movement, but somehow, even after Hiroshima, Nagasaki, the Lucky Dragon fishing boat incident, Fukushima and dozens of other nuclear mishaps, protesters have not managed to halt Japan’s investment in nuclear power.

The push to build nuclear reactors in Japan was aided by postwar censorship, which blocked discussion of atomic radiation, a PR campaign promoting ‘atoms for peace’, and the work of a Japanese CIA asset who proved remarkably effective at getting Japan to buy nuclear technology from the United States. After World War II, the US spent trillions of dollars developing atomic bombs and loading 50,000 of them into strategic bombers and onto missiles. It built a huge industrial base devoted to mining uranium, refining and enriching it, and producing nuclear weapons that grew ever larger and more lethal. Pasting a fig leaf over this arms race, President Eisenhower, in a speech to the United Nations in 1953, proposed using ‘atoms for peace’. Technology good at killing people would be redeployed for boiling water in nuclear reactors. Eisenhower’s plan would keep the nuclear industrial base intact and the scientists who developed this technology employed. It would cement alliances with client states while providing them with nuclear fuel and technology. It would counter Soviet efforts to build their own nuclear alliances, and this transfer of military technology would make certain people very rich.

The CIA asset who proved so adept at pushing nuclear reactors into Japan was Matsutaro Shoriki. Shoriki began his career as a police commissioner in Tokyo skilled at assassinating communists and labour organisers. He was sacked for failing to prevent an attack on Crown Prince Hirohito but rebounded with enough wealthy backers to buy the Yomiuri Shimbun, which became Japan’s largest newspaper, with a circulation of more than 14 million. At the end of World War II, Shoriki was imprisoned for twenty-one months as a Class-A war criminal, but again he emerged as head of a media empire, which this time included Japan’s first commercial TV station and professional baseball team. His ultimate dream was to arm Japan with nuclear weapons. The first step towards this was the acquisition of nuclear reactors. In 1956, the CIA enlisted Shoriki and his media empire to support an ‘Atoms for Peace’ exhibition in Hiroshima. Hugely successful in swaying the Japanese public into supporting nuclear energy, the exhibition began with a Shinto purification ceremony welcoming the atom back to Japan. Shoriki went on to become a high government official and the first head of Japan’s Atomic Energy Agency.

Japan bought its first nuclear reactor from the UK in 1966, but by the 1970s it was buying light water reactors from GE. These were turnkey plants, designed in the United States and assembled in Japan. The first of these was TEPCO’s Unit No. 1 at Fukushima, which began operating in 1971. TEPCO’s president at the time came from Fukushima. Knowledgeable about the risks involved in building reactors in this seismically unstable part of the world, he called his purchase of nuclear technology ‘a deal with the devil’. All of Japan’s nuclear power plants would be built in similar places—coastal areas, undeveloped and poor, despite Japan’s booming postwar economy.

Nuclear power demands a nuclear state: a top-down, secretive hierarchy staffed by technocrats willing to vaunt a dangerous technology over the public interest. The technocrats hide information from the public and even from the governmental bodies meant to regulate them. As soon as Japan flipped the switch on its nuclear reactors, they began suffering the radioactive leaks and explosions that have plagued the industry from its inception. TEPCO may be no worse than anyone else in the business, but the company’s forged documents, cover-ups and lies about nuclear accidents are exposed with surprising frequency.

Large amounts of disinformation and propaganda surround nuclear energy. The industry mounts a formidable PR machine devoted to muddying the issue. Nuclear energy is safe and clean, it says. Nuclear accidents are infrequent and emit small amounts of radiation which may actually be good for you. This theory, called hormesis, posits that low levels of radiation make you more fecund or long-lived. Natural levels of background radiation vary by more than a thousand-fold, and some people do, indeed, seek out the radioactive waters of Ramsar or Kerala as natural fountains of youth. Unfortunately, the evidence confirms what scientists have known ever since Nikola Tesla burned his fingers with X-rays in 1896. No amount of radiation is good for you, and the greater the exposure, the worse the effects.

In a paper published in 2012, Anders Møller, at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and Timothy Mousseau, at the University of South Carolina, reviewed the scientific literature on hormesis. Instead of improving your health, low-level radiation ‘increased mutation rates, impaired immune function, increased incidence of disease, and increased mortality’. Mousseau is visiting Kerala, Bikini, Chernobyl, Fukushima and other hot spots to collect more data. Already a leading researcher on the ecology and evolutionary consequences of nuclear contamination, he expects this research to flesh out in greater detail what we already know. Except for one radioactive-resistant bacterium, Deinococcus radiodurans, which is nicknamed Conan the Bacterium and listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s toughest organism, radiation is a mutagen and killer of living organisms.

So why is nuclear energy currently being promoted as part of the Green New Deal? Air pollution, much of it produced by coal-burning power plants, kills about 7 million people a year, including more than 1 million in China and 60,000 in Europe. The yearly cost for premature deaths and health care is in the trillions of dollars. Given these stark statistics, compounded by global warming, rising sea levels and massive migrations in the face of famine and war, every country in the world—save for the United States, which in 2017 began withdrawing from environmental treaties—has committed itself to finding less toxic ways to produce electricity. Nuclear power was an ageing technology slipping into senescence, with no new nuclear power plants being built in the United States since the 1970s, when the industry seized the opportunity to rebrand itself as ‘green energy’. Aided by PR sleight of hand, the zombie sprang back to life and re-emerged not as a producer of radioactive fallout, but as a carbon-free energy source, jostling centre stage for a photo op alongside wind and solar.

Nuclear energy is not green. The mining and enrichment of uranium are a toxic process requiring large amounts of fuel and energy. To reduce emissions and contain the inevitable mishaps and meltdowns, nuclear reactors are enveloped in concrete, and concrete manufacturing is a big emitter of carbon dioxide. Nuclear power plants rank among the world’s greatest thermal polluters. They require huge amounts of water to cool their cores, and the outflow from this process has raised local water temperatures by many degrees. (Nuclear power plants often shut down during heat waves, when rivers and lakes become too hot to cool them.) This water is also radioactive—at low levels we are told—but every operating reactor is a source of contamination. Hundreds of thousands of people are still displaced from their homes as a result of nuclear disasters at Chernobyl and Fukushima. Adding to this human toll are premature deaths and rising cancer rates. The storage of nuclear waste in spent fuel pools and toxic dumps is another energy-intensive suck on global resources. When one includes environmental costs, government subsidies and other externalities, nuclear technology, far from being green, is black all the way down to its origins as a weapon of mass destruction.

Nuclear research is financed by dirty money—weapons manufacturers and totalitarian states intent on stockpiling plutonium and building bombs—but it is also financed by so-called smart money. Bill Gates at Microsoft, Jeff Bezos at Amazon, Peter Thiel at Facebook and dozens of other Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have invested in nuclear energy. They are tinkering with reactor designs from the 1950s, using thorium instead of uranium, for example, and rebranding these reactors as fourth generation-new-improved models. Other bright ideas include replacing big nuclear power plants with lots of little ones scattered throughout the countryside. Imagine nuclear submarines beached in Iowa. Unfortunately, even if these reactors could be shown to work safely, none of them eliminates the problems of radioactive waste and accidental emissions.

Japan’s public works project in Fukushima—building sea walls, ice walls, incinerators and dumps—is described as recycling or restoring or cleaning up

the area, but there is no such thing when dealing with atomic radiation. Six million tons of dirt have been stuffed into vinyl bags and deposited in Fukushima’s former rice paddies. (This is more than six times larger than the Great Pyramid of Giza.) The soil will remain contaminated for thousands or even millions of years. The government says that Fukushima’s toxic dumps will give way to a permanent solution by 2045, but this date keeps slipping as TEPCO announces one delay after another. In the meantime, as soil and ash from Fukushima get spread around the country, identifying the health effects of the disaster becomes increasingly difficult. Instead of a control population and an affected population, the entire country is affected.

Only one out of every ten Fukushima workers is employed directly by TEPCO. The rest are nuclear gypsies, contract employees recruited from Japan’s underclass. The biggest labour contractor in Japan is the Yakuza, the mafia. The mob in Japan, like the mob in New York or Naples, is capable of doing good work, but its labour record—even excluding bribes, coercion and kickbacks—is spotty. It skims profits by subcontracting seven layers down. It outsources to vulnerable people who don’t speak Japanese, and it operates with minimum regard for worker safety.

Even TEPCO’s direct employees have suffered from lax monitoring. In 2011, workers laboured for weeks with no radiation detectors. When detectors were issued to shift bosses, the bosses reported the same exposure for everyone. This ignores the fact that radioactive contamination is not evenly distributed. Near Fukushima’s reactors, one step in the wrong direction will produce readings that spike to lethal levels. The plant’s vents and smokestacks are known to be particularly hot. The smokestack at reactor No. 1, a 120-metre chimney that workers are desperately trying to remove before it collapses, is radiating a dose of 2 Sv per hour.

In 2011, the rules on radiation levels were changed so that schoolchildren could be exposed to the same level of radiation as adults working in nuclear power plants. Anyone objecting to this twenty-fold increase, from 1 to 20 millisieverts per year, is criticised for succumbing to ‘harmful rumours’. Dissent against official policy is treated as a form of economic sabotage, since talk about radiation depresses the sale of food and other items from Fukushima and reduces tourism. Children are mocked for wearing protective face masks. Refugees from Fukushima are scorned in other parts of Japan, and the Asahi Shimbun reports ‘widespread bullying and stigmatization of evacuees’. It also describes the government ‘enforc[ing] an unspoken understanding that those who resist discrimination by the state (by evacuating, for example) should be punished’. Women from Fukushima are shunned as marriage partners, for fear that their exposure to radiation will lead to genetic mutations, and a new kind of Fukushima divorce has emerged, men returning to the area in far greater numbers than their wives, who insist on keeping their children as far away as possible.

As the Fukushima reactors torched themselves into a mess of molten steel and concrete, burning at over 1,200 degrees Celsius, they melted through their containment vessels, fractured the concrete pads below, and came to rest perhaps in the rivers of groundwater that flow from the alluvial terrace above Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean. In the official version of the story, the reactors were not destroyed by the earthquake. They were destroyed by the tsunami that arrived forty-one minutes later to knock out the cooling pumps and backup generators. Eyewitness accounts describe something different: reactors that were a mess of broken pipes and gushing water before the tsunami arrived, and radiation levels outside the plant that had begun climbing to dangerous levels, again before the wave hit.

Why the reactors exploded and how much radiation was released are also disputed. The official version says the lack of cooling water in the reactors produced clouds of hydrogen gas that blew out the roofs and walls at reactors Nos. 1, 2 and 3, as well as the spent fuel pool on the roof of reactor No. 4. The photographic evidence and intense pulses of radioactivity tell a different story. It was not just hydrogen gas that exploded, but fissile material from the nuclear reactors themselves. The microparticles that one finds scattered around Japan are a key part of this story. They are bits of steel from the reactor cores, pieces of zirconium cladding and nuclear fuel from deep inside Fukushima Daiichi. Under a microscope, one can see that some of these particles are perfectly spherical. Shaped like planets in outer space, they are the product of uranium atoms split in half and dusted like death stars over the shores of Japan.

No one knows how much radioactivity was released at Fukushima. Most of the plant’s dosimeters were swept away in the flood or knocked offline. Readings from US military planes flying overhead and ships sailing offshore differed dramatically from those reported by TEPCO. The same is true for spot readings of air and soil samples around the plant. Most of what we know about nuclear disasters at Chernobyl, Fukushima and elsewhere comes from modelling what is known as the source term. This is the amount of fuel in a reactor, and one has to examine a reactor’s core to guess how much of its source term exploded.

Nine years after the disaster, no one has been able to examine the reactor cores at Fukushima, and no one even knows where they are located. The scant evidence reported so far is troubling. The cores are not melted into solid lumps of uranium mixed with molten concrete and steel. Instead, they are scattered in a mess of hot particles and other debris. After Chernobyl exploded in 1986, the reactor was entombed in a concrete sarcophagus. Designed to last a hundred years, it lasted thirty, before a new US$2 billion shield was installed in 2018. TEPCO rejects all talk of building a concrete tomb over Fukushima. It plans instead to remove the nuclear debris and dump it off site, but so far, as the robots get fried on their suicide missions and radiation continues leaking into the surrounding air and water, every step in this process has failed.

Nuclear energy began its life in secret as a weapon of war. Wilfred Burchett, the first reporter to visit Hiroshima after the attack, wrote that people were dying from an ‘atomic plague’. The existence of radiation sickness was denied by the US government, which moved to expel Burchett from Japan and throw a tight net of censorship around Hiroshima. If it were not only blast and heat, but also an ‘atomic plague’ that killed people, the US feared that its new bomb would be labelled as a chemical weapon, which had been banned after the gas attacks of World War I.

It was not until five years after the bombing of Hiroshima that the US began studying the medical effects of atomic radiation. It created the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), a ghoulish enterprise devoted to collecting the corpses of dead hibakusha (‘bomb-affected people’), estimating their proximity to the nuclear blast and computing dose rates for the effects of atomic radiation. The ABCC had a ‘no aid’ policy that prevented it from offering medical care. Its work was limited to computing how much radiation was required for cell death, cancer, sterility and other debilitating effects. These calculations underlie today’s recommendations for limiting radiation exposure. Originally measured in REMs, which stands for ‘Roentgen equivalent man’, these dose rates are calibrated for the average adult male. The ABCC missed the first five, most lethal years of contamination. It began monitoring the incidence of cancer only in 1988. It undercounted the death toll and miscalculated people’s position in relation to the blast, but apart from these limitations, two facts about radiation sickness are generally accepted by experts in the field. There is no threshold below which nuclear radiation is safe, and exposure to low doses can kill you as effectively as high doses, although at a slower rate.

The ABCC, under a different name, is still in business studying the survivors of nuclear fallout. It continues to tally the effects of radiation in producing cancers, cardiovascular and thyroid diseases, and other genetic effects that are passed from one generation to the next. Radiation affects women and children more than men. Suppressed fertility and birth defects are other legacies. The US government denied the existence of radiation sickness and tried for years to limit reporting on it. A strict censorship regime, preventing any discussion of the bomb and its effects, was slapped on Japan, and the legacy of this regime persists today. Settlers began returning to Hiroshima within a year of the city being bombed. Chernobyl and Fukushima will not be so lucky. Soon after it was attacked, a typhoon scrubbed Hiroshima of radioactive particles. The nuclear isotopes at Fukushima are more long-lived, and the summer typhoons have the opposite effect, bringing loads of contaminated soil down from the mountains and redepositing it along the coast.

For the past twenty years, Anders Møller and Timothy Mousseau have led research teams studying the birds and other animal populations around Chernobyl and now around Fukushima. ‘Every rock we turn over we find damage,’ says Mousseau. The fruit trees at Chernobyl stopped seeding after 1986. The pine trees are bushes, ravaged by mutations. Mousseau and Møller, in over a hundred published papers, have documented that prolonged exposure to low-level radiation increases genetic mutations in animal populations and produces developmental abnormalities, including albinism, small brain size, tumours, cataracts, lowered sperm count, reduced fertility, and even behavioural abnormalities that affect bird calls and mating rituals.

The effects on humans are no more benign. In northern Ukraine and Belarus, neural tube birth defects are six times higher than the European norm. There is a spike in the number of thyroid cancers and babies born with small brains or no brains at all.

‘The layers of toxicity and their interactions are too complex to sort out,’ Mousseau says. ‘Researchers throw up their hands in despair.’ He reports: ‘UN agents work to minimize the story of a public health disaster. They serve their client states, and these are the major nuclear powers. In the 1990s these countries were facing big lawsuits from the people harmed during the development and testing of nuclear weapons.’ So everything was done to lowball the number of deaths and malignant health effects from nuclear disasters.

‘Forty-five million curies of radioactive iodine were released at Chernobyl,’ Mousseau says. ‘Twenty billion curies of radioactive iodine were released from testing nuclear weapons by the US and Soviet Union alone. Global fallout spread mostly in the northern hemisphere. In the same decades rates of cancers, mainly childhood cancers, once a medical rarity, increased in the northern hemisphere. So too did birth defects, fertility problems, and thyroid, and paediatric cancers, which continue to rise. Male sperm counts since 1945 have dropped in half.’

The most alarming medical news from Fukushima concerns the incidence of thyroid cancer in children. A rare disease with a normal incidence of one in a million, in Fukushima prefecture its rate has skyrocketed to one in 2,000. Critics dismiss this as a ‘screening effect’ and claim the cancer surgery on close to 300 children was unnecessary. ‘This is not true,’ says Dr Shinichi Suzuki, at the Fukushima Medical University and former head of the survey team. ‘The cancers that have been treated up to now are too serious and aggressive to explain away with arguments like the “screening effect”. ’

Baba Tamotsu was the mayor of Namie, a city of 20,000 people located eight kilometres north of Fukushima, when the town was hit by the triple disaster of 2011. He witnessed the earthquake and tsunami first hand, but it was from watching Fukushima Daiichi explode on TV that he learned he had to abandon Namie. He had no instructions from Tokyo, no aid or transport. Baba and hundreds of his fellow citizens loaded themselves onto school buses and fled to the northwest—directly downwind of Fukushima’s radioactive plume.

‘I feel pain in my heart but also rage over the poor actions of the government,’ Baba told researchers from the University of California at Los Angeles, who visited him soon after his return to Namie in 2017. ‘It’s not nice language but I still think it was an act of murder. What were they thinking when it came to the people’s dignity and lives? I doubt that they even thought about our existence.’

Baba and his band of atomic refugees settled into gymnasiums and other temporary shelters as the radioactive cloud kept forcing them westward. Finally, they came to rest in prefab metal shelters measured by the size of how many tatami sleeping mats they held. In Baba’s case it was four mats. He lived here for six years, until the government declared parts of Namie open for resettlement. In April 2017, before his death the following year, Baba led a handful of older people back to their ruined city, where they found palm civets and monkeys nesting in the abandoned houses and wild boars roaming the streets.

‘I used to be an advocate of nuclear power. I regret it deeply,’ Baba told the UCLA researchers. He choked up and then broke into tears during the interview. He confessed to failing the people of Japan because he, like other government officials, had believed in the ‘safety myth’ of Japan’s nuclear superiority. The idea that Fukushima was safe for resettlement was another myth. A mere 1–2 per cent of Namie’s former citizens followed Baba back to their ruined city. Everyone else would now be labelled a ‘voluntary evacuee’ and bumped from the rolls.

This was a ‘human-made disaster’, Baba said, agreeing with the official governmental report on Fukushima. TEPCO had been warned that its seawall was inadequate. Company engineers were planning to enlarge the wall when they were stopped as a cost-saving measure. ‘We know … that it was possible for TEPCO to anticipate a giant tsunami,’ Baba said. ‘Seismologists brought in by TEPCO had already warned them of such a possibility in 2008 or 2009 … You can’t call this an example of expecting the unexpected, since a giant tsunami had in fact been anticipated.

‘The piping of the cooling system had already been cracked and damaged by the earthquake before the tsunami hit,’ Baba said. ‘If so, the reactors would have been heating up even before the tsunami arrived, because cooling water had not been getting to the reactor core through the damaged pipes … This was definitely human error, there is no doubt about it.’

Baba had been back in Namie for three months when he was interviewed. ‘I don’t have any neighbours, so I have no one to talk to,’ he told the UCLA researchers. ‘I can’t assign monetary value to what we’ve lost, but I never thought that I would end up having such a miserable life.’

TEPCO offered to pay Baba 100,000 yen (less than US$1,000) for his ‘mental anguish’. The sum was based on payouts for auto injury claims. ‘I was furious, wondering what the hell they were talking about,’ he said.

His eyes filled with tears again when he was asked to describe what it was like to return home after living for six years in a refugee camp. ‘There used be about six hundred houses and buildings along the ocean, but they were all swept away by the tsunami. When I saw the aftermath, I knew something incredibly awful had happened. Actually, I couldn’t even look at the ocean for about a year and a half after the tsunami. I was just so scared.’ He also avoided looking at workers from TEPCO. The sight of them made him too angry.

Eight kilometres north of Namie, in Odaka, an area known for its samurai forts and temples, Mrs Tomoko Kobayashi runs a ryokan, a country inn that was inherited from her grandmother and her mother. Mrs Kobayashi and her husband, Takenori, who had been living in an eight-tatami-mat shelter, were among the first people to move back to Odaka when the area was reopened to settlement in July 2016. They gutted the interior of their ryokan, washed down everything reusable, planted flowers along the road between their hotel and the train station and declared Odaka, with its horse farms and long tradition of silk weaving and samurai festivals, open for business.

Not believing anything they were told by the government about radiation levels in the area and ongoing emissions from the power plant, they took one more important step. With money raised by a TV telethon and equipment donated from Germany, they opened their own radiation testing lab. They organised hundreds of volunteers to canvass the surrounding area, measuring and mapping its radiation. They collected information from around the world on what crops to grow in nuclear exclusion zones. And they began making regular visits to Chernobyl to learn from their colleagues with thirty more years of experience of how to live in irradiated landscapes. ‘You measure everything and keep measuring,’ says Mr Kobayashi, a retired labour negotiator. ‘That’s the most important lesson we have learned from Chernobyl.’