Six Records of a Floating Life

Shen Fu, translated by Alex Fang

Printim Editions: 2025

.

When I saw my apartment building’s doors chained shut one morning in July 2022, I had to change more than just my plans for the day. Living in China under its zero-Covid policy forced me to adapt in a volatile situation over which I had no control. So, I chose to romanticise my life.

This principle restored my sense of agency. Shenzhen, the megacity I lived in at the time, was now only as big as my apartment walls could hold. Mornings took on a slow, mindful ritual: I’d wake and feel the softness of my sheets. I paused to smell freshly brewed coffee. Instead of longing for what was missing, I appreciated what I had. I lived in the present and looked for moments of beauty in the mundane.

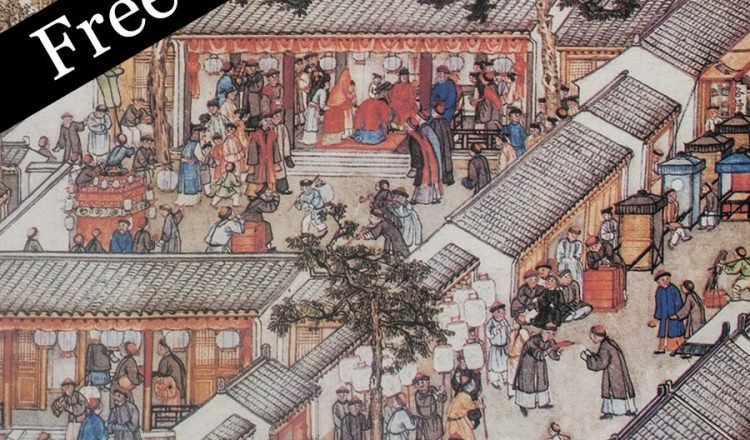

The phrase “romanticise your life” emerged as a popular mantra across American social media during the pandemic, but the concept is nothing new. More than 200 years ago, in Qing dynasty China, Shen Fu wrote about the need to “take things as they are” in his autobiographical Six Records of a Floating Life. Shen, an impoverished and unfulfilled scholar, lived mindfully and embraced minimalism. His approach to life was “one of economy but also of elegance”—he took simple meals, arranged flowers, and enjoyed the fragrance of burning incense.

That’s not to say he ever stood still. Shen floated through life, working odd jobs and travelling widely across China. In her crisp new translation, Alex Fang notes that Six Records of a Floating Life, like its author, drifted: it was probably finished in 1808, but wasn’t discovered until 1877, when four of the six “records” were found in manuscript form at a secondhand book stand in Shen’s native Suzhou. Shen found little success in life, but, some fifty years after his death, his autobiography became a classic of the Chinese written word.

What makes Six Records of a Floating Life so readable today is how its themes—simple living, intellectual frustration, and nostalgia—have sharpened over time. Just as readers turned to it during the decline of the Qing dynasty, it continues to provide comfort and a means of self-preservation in an uncertain world.

Shen’s life, as he records it, was one of downward mobility. He was born in 1763 into a family of legal advisers and surrounded himself with like-minded scholars. Yet he failed the imperial examination, denying him a position of high status and a stable income in the bureaucracy. Shen came to see ambition as futile in a rigid imperial society where merit counted less than connections. His resignation to a modest living is not unlike that of contemporary Chinese youth who choose to “lie flat”—to do only the minimum required rather than try to overachieve in a stagnant economy with diminishing returns. Many, like Shen, have drifted to far-flung places, such as Dali in the southwestern province of Yunnan, to escape the high cost and high pressure of big-city life.

The frustrations of Six Records of a Floating Life also anticipated the sharper critiques of the old Qing society that would follow. In 1919, Lu Xun published the short story ‘Kong Yiji’, a scathing portrait of a failed scholar thwarted by the same examination system that kept Shen in precarity. Again, the parallel extends easily to today’s graduates in China, who, like Shen and the character Kong Yiji, spend years poring over texts only to find their hard work yields fewer prospects than promised. Amid layoffs and record youth unemployment in the present day, China’s young people are once more seeing the civil service exam as one of the few reliable paths forward in society.

Lu ushered Chinese literature into the modern era, yet Shen foreshadowed him in another, more significant way: Six Records of a Floating Life is—especially in this new translation—anecdotal and conversational, much like the vernacular Chinese writing that Lu pioneered in the early twentieth century. And unlike the grand narratives of novels from the High Qing era, Shen’s writing is intimate in scope. He wrote that, as a child, “I would often squat down so that I was level with the flower-bed itself and look closely. Weeds became forests, ants and bugs beasts; the little protrusions on the ground were hills and hollow valleys.”

Neither does Six Records of a Floating Life follow the chronological form of a typical memoir; instead, the book is arranged in thematic chapters (or “records”) that vary in tone, topic, and even genre. The first record details the tender but ultimately tragic romance between Shen and his wife, Chen Yun. The next turns to their shared pleasures of floristry and art, at times reading like an early self-help guide. In the third record, the mood darkens as Shen recites the couple’s hardships and the events leading to Chen’s death. Finally, Six Records of a Floating Life jumps genres again, journeying with Shen across Chinese provinces like a travelogue.

Shen is, by his own narrative, “candid, carefree and without constraints”, and his approach to autobiography reflects that impulsive nature. What ties these floating chapters together is the thread of his romance with Chen. As the ideal foil to her hapless husband, Chen was resourceful. She loved to bind together old, broken books—a metaphor for her place in Shen’s life and in the text itself.

Their romance—enduring as one of the greatest of its time period—is told through everyday moments. In one anecdote from their courtship, Shen returned late to her home to find that Chen had secretly saved a bowl of congee for him, after telling her family that there was no food left. What is love but small acts of kindness like this?

The marriage is especially striking today for its relative equality within the historical context. Shen, who prompts Chen to speak her mind, recognises her intelligence as equal to his own, despite her lack of a formal education. His portrayal of her is unlike that of other women in classic texts (within the Chinese and Western canons), who are often flattened into virtuous symbols or cautionary tales. Neither does Shen shy away from Chen’s flaws, particularly her perceived missteps as a daughter-in-law, for which the couple paid dearly.

The focal point of her complexity comes in her relationship with Han Yuan, a courtesan with whom she formed a deep attachment. Chen introduced Han to Shen, hoping to establish her as his concubine, an idea Shen resisted.

“As an impoverished scholar, how dare I entertain such a fantasy? Moreover, our bond as husband and wife is deep and steadfast. Why should I look elsewhere?”

“Oh, but I love her!” Yun laughed and said. “Just leave the matter to me.”

Why was Chen so enamoured of Han? One can interpret Chen’s matchmaking as strategic: by choosing a second wife herself, she could reassert authority within the marriage while managing Shen’s wandering affections. But even when taking Shen’s account at face value, it’s easy to read it as a glimpse of same-sex attraction in late imperial China. When the arrangement falls through, Chen is devastated. “Of all things,” Shen writes, “this might have been the final cause of Yun’s death.”

Chen’s depiction is, of course, inseparable from Shen’s account, which he wrote some years after she died of an illness (and perhaps a broken heart). Everything we know about his wife comes through his paint and brush, her portrait coloured by his nostalgia and grief. She is dutiful and outspoken, but her inner thoughts and motivations remain a mystery. Still, the fact that Six Records of a Floating Life gives the modern reader different ways to read Chen’s character proves the richness of her portrayal.

To read works of the past is to escape from the present—or so we hope. We inevitably filter our approach to the classics through our experiences and the world we want to leave behind. Similarly, the memories in Six Records of a Floating Life are told through Shen’s longing for an irretrievable past. In one passage, he reminisces about entertaining friends with Chen, only for the tone to shift: “Yet now we are all scattered in different places, like clouds parted by the wind. The woman I loved is gone; jade broken, incense burned. How hard it is to look back!” By that same token, Shen wrote his account of domestic bliss with Chen while haunted by their earthly separation.

In her translator’s preface, Fang writes, “Something beautiful was once had and is now lost. The poet cannot help but look back, aware that what remains is only the poem, not the person.” Despite its depiction of pleasure and romance, Six Records of a Floating Life is, underneath it all, an elegy. Yet, as an attempt to preserve what is gone, the book endures as a reminder to treasure what we still have and what we will someday mourn.

![]()

- Tags: Alex Fang, China, Issue 41, Sebastien Smith, Shen Fu