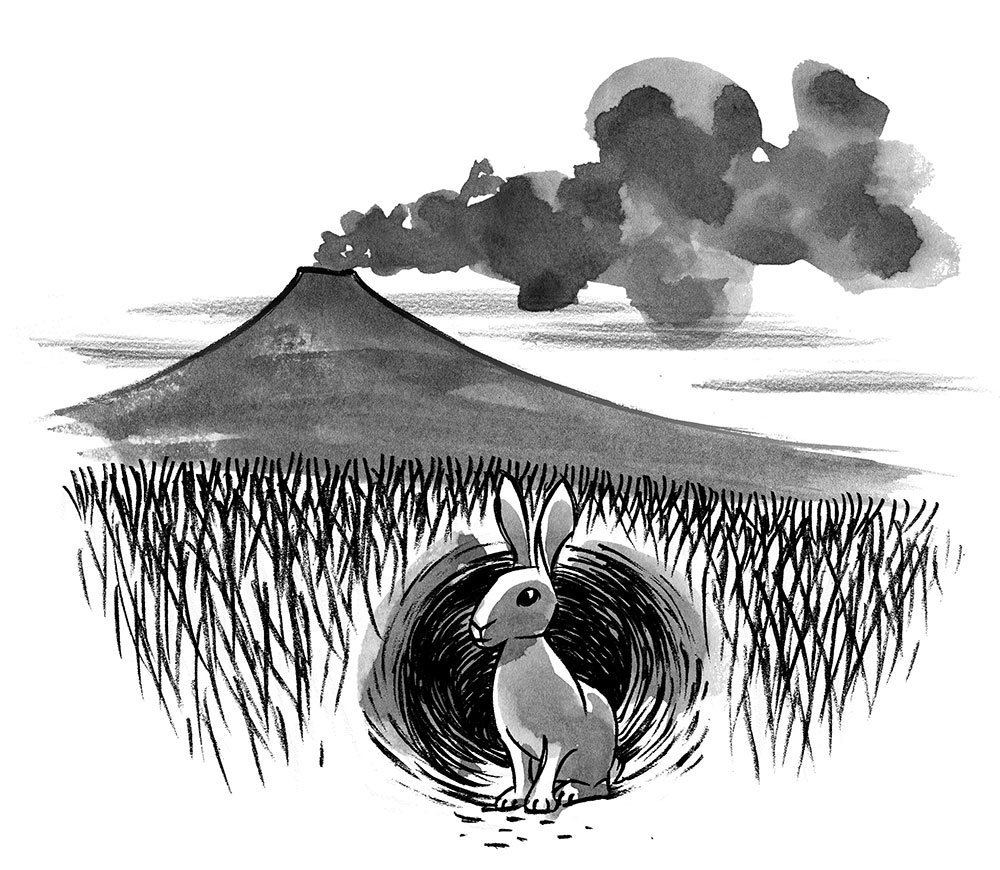

Her rumbling feels like a hum now, like when Ibu would hold my little baby body and rock me from side to side, except this rocking is more like up and down, like a seesaw. She’s been releasing red smoke for two days now, and Ibu says nobody knows when her fire is supposed to stop. Ibu says she is angry with us, and that we have to sing and pray a lot more now, so I wake early in the mornings, when the sun is only halfway high, and fold coconut leaves on the concrete floor of our home, while Ibu lights incense and hums Maaf, sorry to Mother Agung.

Bapak looks afraid today. He’s been outside all morning smoking cigarettes and drinking arak while Pak Wayan, one of our new neighbours, folds the waterproof sheets of his house back up again and his wife scoops rice into brown paper for later. Bapak loves arak, but Ibu tells me it tastes like burning vegetables in your throat. I don’t like vegetables. Ibu doesn’t drink arak because she says the women aren’t supposed to, and it makes you drunk. I don’t notice Bapak smoking as much with all the thick clouds Mother Agung is blowing through the house. It all becomes one big exhale. It’s like our whole village has become the little bowl he ashes his cigarette into; the grey from Mother Agung’s smoke sticks to everything.

We knew Mother Agung was sick because she rumbled for weeks, like my stomach in the morning, but much heavier. Everyone said she’d been sleeping for almost one hundred years, so it made sense that she grumbled so big. Sometimes it was so loud I could feel it under my toes, and through my whole body. People in the village were very chatty about it until she rumbled louder and started to smoke, and then everything got quiet. Some mornings the smoke was so thick you couldn’t see her at all, and other days she towered high and mighty over the ocean and the crowds of green trees growing around her base like a warm blanket. Two weeks ago, people started moving away from her and travelled farther south into our village to stay safe. Ibu says this was an order from the government. They brought their cows and big waterproof sheets and walked around talking to the neighbours to see if there was room to sleep. I heard some of the children talking about all of the dead chickens they left behind, and they kept sarongs wrapped over their noses and mouths even though the falling ash wasn’t as bad in our village. I think their parents told them to.

- Tags: Becca Stine, Indonesia, Issue 18