Myanmar is a country gripped by civil war and Yangon is a city where daily life is muted by uncertainty. Yet, this January, a show of writing and art drew a crowd of 300 people to its opening.

The Myanmar Photo Archive (MPA) was set up by Lukas Birk, an Austrian artist and collector, and consists of photographs spanning the nineteenth to twenty-first centuries. Rethink, a two-year collaboration between MPA and Goethe Institut Myanmar, ran an exhibition in Yangon from 15–30 January 2024. The project began in 2023 with an international call for artists, writers, filmmakers and academics to reinterpret Myanmar’s history, each through a photograph selected from the archive. Thirty-five creative works were presented to the people of Yangon.

The following is a conversation between an arts worker and a commissioned writer, in which we consider how working with the archive allows a ‘rethinking’ of the past and how it shapes the future. Names have been removed due to safety considerations, given the situation in Myanmar. The exchange has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Writer: The idea of revealing stories behind an archival image is a rich premise for a writer. One of my reasons for joining the call was the chance to make my own personal and hidden mixed race, Anglo-Burmese history visible. My contribution is a form of ekphrasis—writing that riffs off or describes a visual artwork. But I feel my work and the work of the project itself taps into the etymological roots of ekphrasis—which are to ‘tell’ or speak ‘out’ or ‘about’ something which is about our own connection to history. Do you think other artists were motivated by a similar notion?

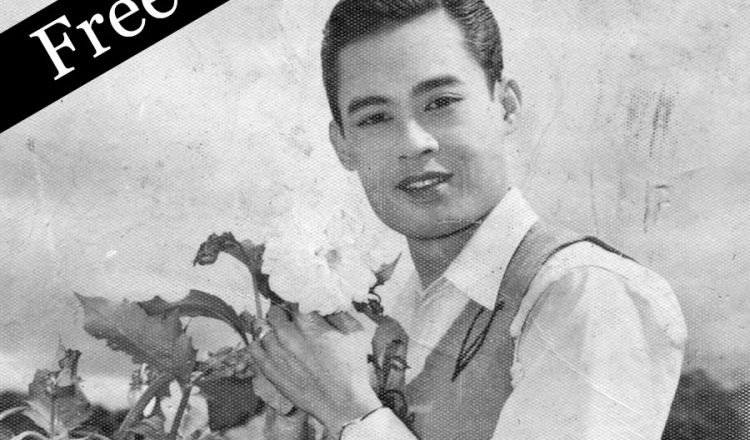

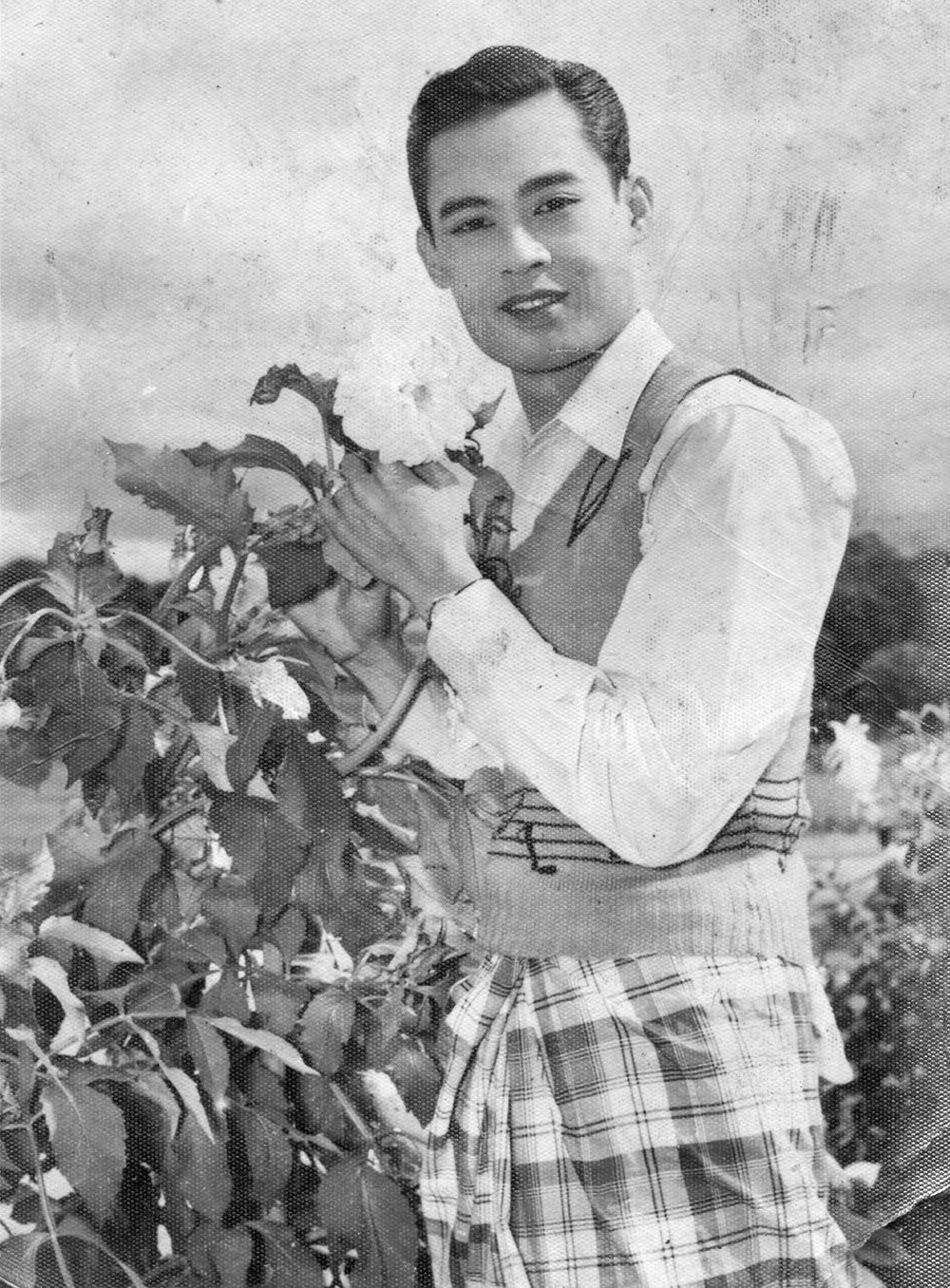

Arts Worker: All the proposals had an innovative, very specific idea for reinterpreting the history of Myanmar through the archive. All the artists felt strong emotional connections to their choice of image. For example, one of the works reinterpreted was an image of a man standing beside a flower. I think this man may have been an actor, because he’s wearing makeup. Beside the flower—a very feminine object—he, too, looks very feminine and beautiful.

Many people would see just an old photo of a guy standing beside the flower. Maybe he’s not a gender fluid person, maybe he’s not gay. But the interpreting artist is gay, so he interpreted this as the free expression of a man who isn’t afraid to embrace femininity.

Writer: The image I was drawn to was of two boys sitting on the marble steps of the Bank of India. They’re oblivious to the grandeur of the building and are reading a comic book together. It reminded me of my mother’s stories of her weekly comics from Smart & Mookerdum in Rangoon, sent on by train. It was a personal connection to the past.

Arts Worker: These retro things are very popular here now. Some of the artwork took advantage of this and are what I call time-travelling pieces because they intentionally take the audience back to the past.

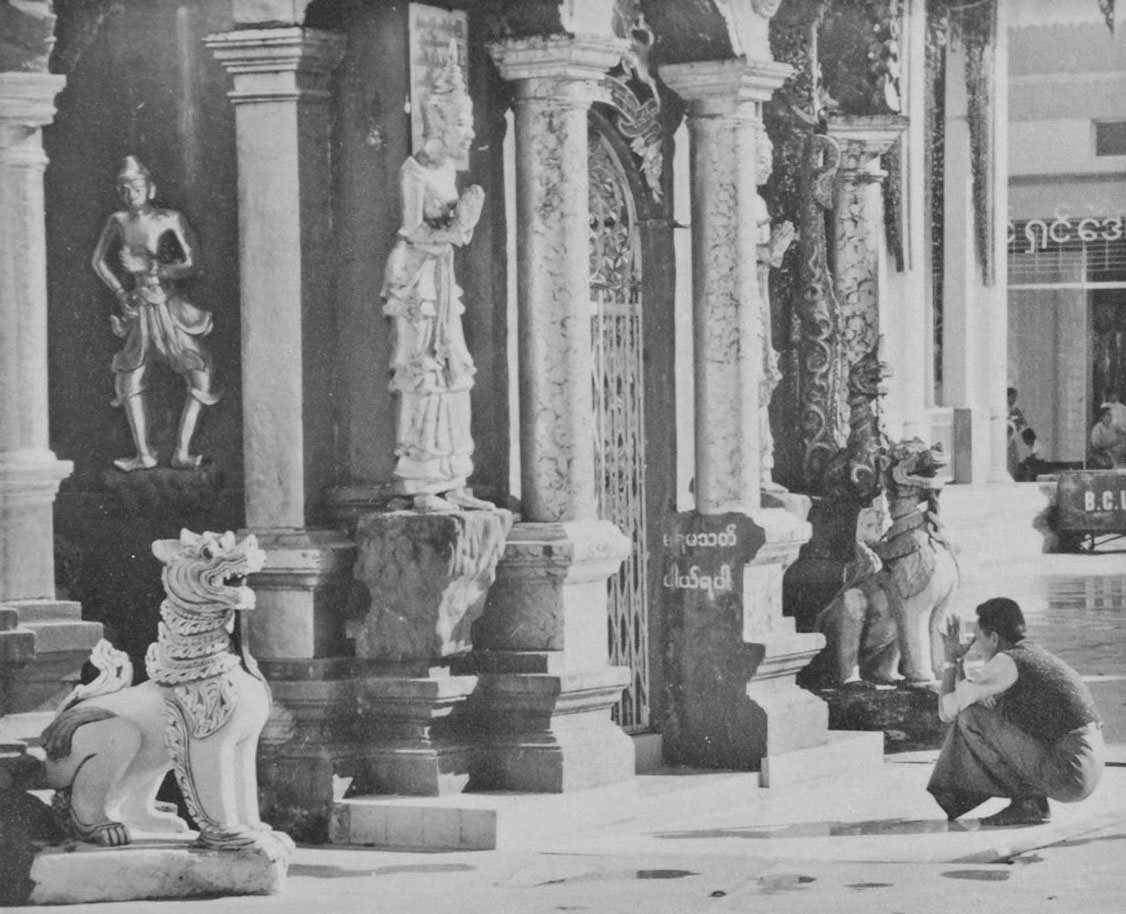

Some of the archival images that inspired the artworks, such as posed studio shots, also promote this ‘time travel’. The audience thinks, Oh yeah, when we were young, we used to go to those studios to have family portraits. And then there are other images and objects from older times that also attract people.

Writer: For locals, ‘rethinking’ has an additional meaning: not just seeing the past anew but also accessing and sharing these personal, informal histories that aren’t captured by the state’s archive or libraries, or in the official narratives.

Arts Worker: That’s right. The project includes digitisation workshops as well as talks about collections and archives. Through these talks and events, we’ve met other collectors telling different stories through their own collections. People are motivated to share and the public is hungry for this kind of history.

Writer: What also appealed to me about this project was my sense of nostalgia for the physical photograph. I have dozens of family photos from the 1990s and early 2000s, sitting in boxes, plus photos inherited from my parents and grandparents. I almost never look at them. Yet they’re a foundation for my life, in a way, because they keep a record. I’d be devastated to lose them.

Arts Worker: I think what motivated Lukas Birk to build the archive in the first place was simply that he found all these photos—in places like flea markets—and thought it’d be a terrible thing to lose them all. They’re a record. But they’re mysterious; you don’t really know what’s in them. His motivations were artistic and out of respect for the form. The Myanmar Photo Archive now holds the largest collection of Myanmar’s independent vernacular photography. But whenever Lucas looked at these photos, he was aware he didn’t know the stories behind them. These are background stories that locals might be able to tell.

Writer: How can this archive be made more available to local people? Who can be said to ‘own’ an image? And how can these physical photographs be kept safe?

Arts Worker: There are plans for incubator programmes to make the archive more inclusive; there isn’t much material from ethnic minorities at the moment, for example. But with the current conflict, it’s very, very difficult to collect those images now.

Myanmar doesn’t strongly enforce copyright laws, so the archive restricts the use of materials to artists and educational researchers only—no commercial use. Whoever took those photos just gave them away. But for the next generation, this could be [a precious photo of] their grandfather or grandmother. These rules limiting use are a good thing.

The underlying issue is that more and more people are relocating. Photos and other objects that have cultural, historical, even sentimental, value are at risk of destruction in this conflict. Also, in Myanmar, humidity is extremely high. A photographic archive needs an organisation that can store these pictures properly and can afford to pay people with the technical knowledge to maintain them in good condition. This is a challenge. The grant runs out this year; what happens after that, I don’t know. How do you sustain or even extend an archive like this during a conflict?

There are plans for workshops to teach people how to digitise and store photos using their phones. An expert will be teaching people how to discern the age of a photo by looking at its colours. There’ll also be more talks on building your own collections and archives. We need these kinds of archives. Archives that are locally owned and run are important; they’ll be of value to the people of Myanmar long after the conflict ends.

Myanmar Photo Archive is planning further events in Yangon, Singapore and Chiang Mai.

![]()

- Tags: Free to read, Issue 37, Khin, Michelle Aung Thin, Myanmar