At a ceremony on 25 September 2023, the Royal Academy of Cambodia (RAC) announced the official release of the updated Vachananukram Khmer, or the Khmer Dictionary. Developed by the RAC’s National Council of Khmer Language (NCKL), the dictionary is available both in print and as an app, designed to be broadly accessible to the Cambodian public. Each of the event’s three speakers—Vongsey Vissoth, the deputy prime minister, Sok Touch of the RAC and Hean Sokhom of the NCKL—stressed the updated dictionary’s importance for efforts to “respond to the needs of Khmer language users and… the growth of Khmer society” as well as its “historical import and its contributions to a more robust Khmer identity”.

The release of the updated dictionary is intriguing for the ways in which it evokes—and diverges from—another, much older dictionary-related public notice. The 30 July 1938 edition of the early Khmer-language newspaper Nokor Wat reported the publication of the first volume of the Vachananukram Khmer in a brief paragraph, tucked away on the penultimate page. Like the NCKL, the Royal Library—publisher of the original dictionary—emphasised the text’s contributions to Cambodian society, suggesting that the dictionary would be indispensable for “anyone who wishes to cultivate their sophistication in the literary arts”.

These two announcements serve as useful entry points into the Vachananukram Khmer and its dramatic entanglements, across more than a century, with Cambodian history. In tracing its trajectory from its origins in the colonial era through to the present day, we catch a glimpse of the ways in which the Khmer language has been deeply implicated in efforts across generations to define and delineate notions of Cambodian nationhood and politics.

Today, as the Cambodian political system navigates Hun Sen’s transfer of power to his son after nearly four decades of rule, the questions that the Vachananukram Khmer has evoked—tensions between tradition and modernity, the importance of national unity in a volatile world—are as relevant as ever.

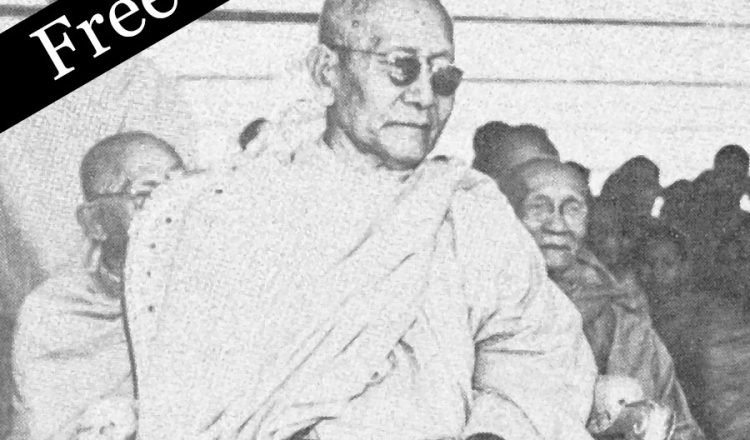

The NCKL traces its updated dictionary to the original Vachananukram Khmer, first published between 1938 and 1943. The dictionary’s fifth and final edition, published in 1967, is widely known today as the Vachananukram Chuon Nath, named for the Venerable Chuon Nath, the monk who dedicated the final four decades of his life to the project of compiling and perfecting the country’s first Khmer-language dictionary.

Nath took charge of the project in 1926, after a previous commission, established in 1915, proved unable to resolve disagreements around orthographic and lexical conventions and was later dissolved.

Over the next twelve years, Nath led the effort to develop a comprehensive accounting of the Khmer language. He did not work in isolation: his work on the dictionary developed alongside, and as part of, a nascent nationalist movement determined to map the cultural and historical contours of the emergent collectivity known as the Khmer people.

The impetus for conceptualising the ‘Khmer nation’ emerged out of and in response to the colonial encounter, as French and Cambodian scholars, intellectuals and bureaucrats were brought together in a complex array of ideological interactions and exchanges. By the 1930s, Cambodian and French scholars alike largely understood Khmer culture and identity as rooted both in Theravada Buddhist tradition and in the history of Angkor, cast as the civilisational and cultural fountainhead of twentieth-century Cambodia. Yet while French colonial administrators and scholars largely conceptualised Khmer culture in racially absolutist terms, emphasising the ‘fall’ of Angkor to justify the ‘civilising mission’ of the colonial regime, early Khmer nationalists instead cast their rich cultural heritage as evidence of the inherent strength and resilience of the Khmer people.

Nath’s Vachananukram Khmer similarly enacted a radical mediation of French colonial influence, as he deployed the dictionary to legitimise the Khmer language among French scholars. The orthographic and lexical conventions that Nath’s dictionary established—its accepted spellings and words—tethered modern Khmer both to Old Khmer, the language of the builders of Angkor, and to Pali, the canonical language of Theravada Buddhism. The 1,858 pages of Nath’s Vachananukram Khmer thus rejected colonial assumptions about Khmer cultural inferiority and civilisational degeneracy, and instead elevated the Khmer language, and the people who spoke it, to a position of legitimacy and authenticity.

Nath’s project bolstered early nationalists’ efforts to establish the cultural authenticity of the Khmer people as a precursor to more overt agitation for political sovereignty. Independence arrived at last in 1953, yet it did not bring the constitutional democracy that many early politicians had hoped for. Instead, Prince Norodom Sihanouk consolidated power, effectively turning Cambodia into a one-party state by 1955.

Over the next two decades, Nath’s Vachananukram once more found itself invoked as a symbol of political positionalities. Sihanouk, eager to bolster his political authority through appeals to Angkorian grandeur and Buddhist ethics, sought to incorporate Nath into the fold of his regime’s symbolic architecture, bestowing a range of honours and titles on the monk throughout the 1960s.

Yet Sihanouk’s suppression of political opposition inspired a generation of modernist authors to turn to language and literature to express their discontent. These authors rejected the orthographic and lexical conventions of Nath’s Vachananukram Khmer, instead writing in a reformed orthography promoted by Dr Keng Vannsak. Alongside their critiques of Nath’s dictionary as arcane and archaic, ill-suited for the needs of the modern nation-state, we read parallel critiques of the Sihanouk regime. Indeed, shortly after Sihanouk’s fall from power in 1970, the Lon Nol regime officially adopted Vannsak’s reformed orthography for government communications.

For the next four decades, the Vachananukram Chuon Nath was largely sidelined. Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge abolished formal education; afterwards, a series of successive regimes followed the Lon Nol government in endorsing the reformed orthography.

This changed in 2010, when Hun Sen, the prime minister, unexpectedly announced the restoration of the Chuon Nath standard. Speaking at an assembly at the National Institute of Education, Hun Sen suggested that it was the country’s use of multiple different writing standards that held Cambodia back economically. “We must be unified in our writing,” he told his audience. Nath’s Vachananukram, Hun Sen suggested, would provide the foundation for linguistic, and thus social and political, unity.

In the years since, the government of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party has gone to great lengths to revise the dictionary for the twenty-first century, culminating in September’s official release. The 1967 Vachananukram Khmer was digitised in 2016 through a joint initiative by the Royal University of Phnom Penh and the Ministry of Economy and Finance; the following year, Hun Sen signed a decree establishing a committee to update and modernise the dictionary. Earlier this year, after the December 2022 release of the beta version of the NCKL’s Vachananukram Khmer, Hun Sen, presiding over the National Culture Day celebrations on Koh Pich, urged his audience to strengthen Khmer literary arts through adherence to the Vachananukram Chuon Nath, now available on smartphones.

Official discourse surrounding the project frequently invokes the dual—and at times competing—themes of preservation and development, often framed in the context of Cambodia’s changing place within the modern world.

Such concerns speak to what the linguistic anthropologist Cheryl Yin describes as “linguistic anxiety”. Comments about the Khmer language may often be understood as commentaries on “the country’s current political, economic, and social conditions”. In the current regime’s efforts to bolster the Khmer language as a unified entity, protected against foreign intrusions, we may read official anxieties around increasing globalisation, social and cultural change, and the political instability that they portend.

A government-approved Vachananukram Khmer thus becomes a mechanism for reasserting a degree of social and political control. The Venerable Chuon Nath’s dictionary endures today as a symbol of Khmer intellectual achievement and cultural accomplishment. Much like Sihanouk in the mid-twentieth century, the ruling party today, confronted with shifting social and political conditions both at home and abroad, has sought to bolster its own political legitimacy through appeals to such a potent symbol of the nation.

Yet the history of the dictionary also suggests another reading. The dictionary was produced in defiance of the racial logics underpinning a brutal and oppressive colonial regime; in the post-independence era, despite repeated efforts to incorporate it into the political economies of successive regimes, the Vachananukram—and the Khmer language more broadly—remained a site of active engagement through which to contest state-mediated delineations of national identity and community. There have been many attempts to fix it in form and meaning, but the Khmer language has endured as a destabilising force, its fluidity forever unfolding a discursive space in which to renegotiate, reformulate and redefine.

Today, as a new generation of authors, scholars, intellectuals and everyday speakers take part in global literary, academic and other online communities, language remains a central site of negotiation and mediation. For when it comes to language, no scholar, dictionary or regime ever has the final word.

![]()

- Tags: Ben Rost, Cambodia, Free to read, Issue 33