“Man survives by his ability to forget.”

Richard Flannagan, Narrow Road to the Deep North

At the Hellfire Pass in Thailand’s Kanchanaburi province, the landscape is wild and beautiful. In between clusters of visitors, what is striking is just how quiet it is. Apart from the occasional insect or bird, everything is still beneath the gently swaying bamboo. A tropical storm grumbles in the distance. The vegetation on either side of the abandoned railway is a vibrant green. It is impossible to imagine the scene seventy-five years ago.

Between June 1942 and October 1943, the Japanese Imperial Army forced 255,000 Allied prisoners-of-war and Asian labourers to construct a railway running from Thailand to Burma. Working in the blazing sun, or in monsoon downpours, and severely malnourished, tens of thousands succumbed to diseases like malaria, beriberi and cholera. Many died from exhaustion, overwork and starvation. Or were executed.

The Hellfire Pass — also known by the Japanese as the Konyu Cutting — got its name because, in the rush to complete the railway, prisoners were forced to cut a pass through rock in twelve-hour shifts through the night. Using the most basic tools, they were aided by the light of burning torches. The sight resembled a scene from hell.

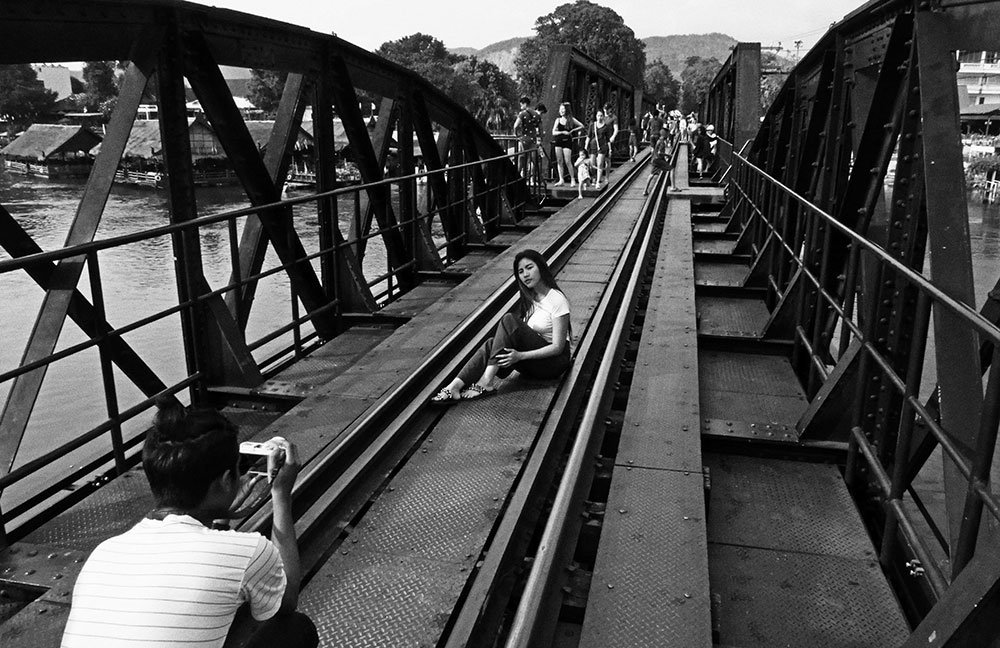

Made infamous by David Lean’s 1957 film, The Bridge on the River Kwai, and more recently The Railway Man, the railway has become a byword for war crimes. But many Thai visitors remain unaware of the true story behind its construction.