The Second Link: An Anthology of Malaysian & Singaporean Writing

Edited by Daryl Lim Wei Jie, Hamid Roslan, Melizarani T. Selva and William Tham

Marshall Cavendish Editions: 2023

.

In 1963, an EP record titled Malaysia For Ever was produced to commemorate the formation of Malaysia. On the back was a brief message from Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Federation’s first prime minister, lauding a moment when “the peoples of Malaya, Sarawak, North Borneo, Brunei and Singapore are about to be forged into the Malaysian nation”. Brunei later pulled out of the agreement before Malaysia Day on 16 September that year and Singapore left to form its own independent nation in 1965.

More than a historical curiosity, this detail bespeaks the entangled pasts of these former British colonies and their desire for solidarity amid a charged awareness of varying cultural and economic priorities. As Paul Augustin and Jocelyn Marcia Ng explain in their essay ‘From the Archives: Music and the Formation of Malaysia’, songs were composed and recorded in anticipation of a successful union despite other troubled events of the 1960s, such as the aftermath of the Malayan Emergency, the Brunei Revolt and the Konfrontasi.

Much of the impetus behind The Second Link: An Anthology of Malaysian & Singaporean Writing is derived from these residual and unresolved energies of the former Malaya and its transition into contemporary societies and cultures. However, as the editors explain in their dialogue-in-print (which takes the place of an editorial introduction), they wanted to curate writing that moves beyond the “exhausted metaphors and dusty tropes” of the longstanding rivalry between Malaysia and Singapore, where both, despite being siblings, evince fundamental differences in national politics and philosophy.

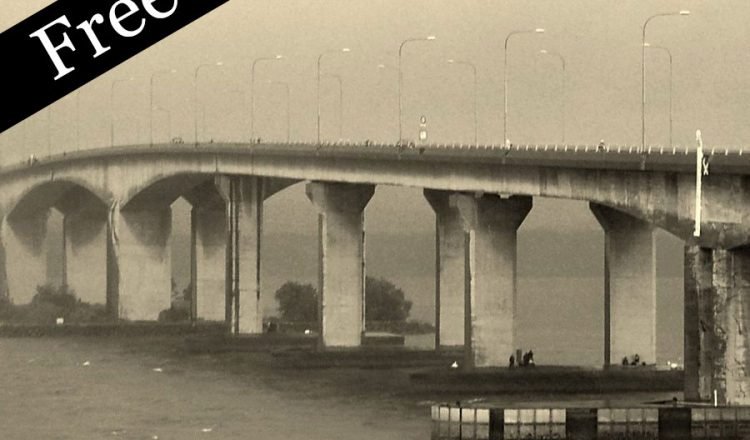

Consisting of fiction, creative non-fiction, visual art and poetry selected from an open call, The Second Link makes for a fine read at the intersection of the literary, historical and sociological. The title of the anthology alludes to the second cross-straits bridge between the southern Malaysian state of Johor Bahru and Singapore. Known officially as Tuas Second Link, it was built to ease traffic conditions on the main Johor-Singapore Causeway, though the bridge acquires an additional symbolic charge when considered against the anthology’s intent to reassess the present in light of more generous attitudes towards the founding of both countries. In the same spirit, the volume’s entries, for the most part, respond in nuanced and measured ways to the longstanding contrasts between Malaysia and Singapore, with fiction pieces like ‘the reverse of a bridge lies between two borders’ by ila and ‘The Real Little India’ by Sumitra Selvaraj articulating the discomforting humanity of being forced to make sense of one’s circumstances through a relentless comparison between the two nations. Undoing false myths about Singapore as a first-world model for Malaysia, and Malaysia as the resource-rich hinterland to whom Singapore must continually pay tribute, the anthology dwells at length on loyalties divided across extended family ties and class differences.

The complex inheritance of the region’s immigrant histories and racial politics concerning the use of English is present in the poem ‘The Claiming Game’ by Malachi Edwin Vethamani. Many of the pieces also delve into earlier time periods: ‘Amateurs’ by Kevin Martens Wong features a time-travelling Eurasian stage player who returns to the nineteenth century, only to find it the height of a Kristang-speaking Melakan Empire; ‘Hang Tuah and the Crocodile’ by Ng Yi-Sheng is half-essay and half-speculative in genre, delving into cinematic portrayals of the Malay hero of fifteenth century Melaka, alongside a naturalist study of his adversary, the white saltwater crocodile, in its various guises as leather handbag and guardian of the waters. The Second Link, collectively, is less historical fiction than historical meta-fiction, where the comparative composition of the anthology as genre allows readers to consider parallels and departures across various pieces.

Weighted in favour of prose, rather than poetry, The Second Link is also an important publication for deviating from the traditional emphasis placed on verse in earlier Malaysia-Singapore literary anthologies such as The Flowering Tree (1970) and The Second Tongue (1976), another possible namesake. The sheer hybridity of prose forms on offer is a delight, ranging from essayistic commentaries to strictly realist fiction, and speculative fables that re-constellate national narratives. The result is a broadened imagining of the geographies and histories of Malaya and a greatly enriched portrayal of the 1950s to the 1970s in its everyday textures. ‘Belonging’ by Anitha Devi Pillai is a personal recount of the author’s Malayalee origins, routing through “Singapore, Malaysia and Kerala”—each three-syllable word meaning home on equal but different terms. ‘Driving North’ by Zhang Ruihe is a fictional narrative that is the literary equivalent of photographic realism. Presented as the journal entries of a certain Goh Wee Kiat, translated from Chinese by Rachel Teo, it traces a car trip taken by a group of Chinese-educated friends up from Singapore through the peninsula. Occupying a liminal space between fiction and history, between the abjected pasts of Chinese student activism and an English-speaking Singapore condensed in the translator’s Anglo-Chinese name, Zhang’s piece implicitly queries our responsibilities to factuality in light of fiction’s prerogative to generate alternative memories. Most striking too are the inclusion of ‘South of Memory’ by Sharmini Aphrodite and ‘Referendum Rains’ by Rachel Fung, which bring readers to the Bornean states of Sabah and Sarawak, often sidelined by the interminable contest between Malaysia and Singapore. Bringing up the rear of the collection are two non-fiction pieces that foreground the natural heritage and shared ecologies of the two countries, though this reviewer wonders if their inclusion seems more thematic than organically in conversation with earlier entries.

While The Second Link is a volume to be enjoyed mainly for its amplification of historical and social contexts, there are a number of pieces to be savoured for their wit, humour and often madcap sense of style. Pithy statements about the hackneyed Malaysia-Singapore rivalry abound: the narrator in ‘Foot Massage’ by Mohamed Shaker declares “we just landed on either side of the bridge”. ‘Annals’ by Joshua Ip will be read first with outrage, and then with nervous laughter at the absurdity of such outrage, by any concerned citizen of Malaysia and Singapore. The provocative poem lists a series of fictional Malaysia-Singapore wars between entities as diverse as the seventeenth Nusanataran Republic and SING Pte Ltd, over causes such as chicken rice and to expend excess budget. More subtle are the accents and tones from across diverse sociocultural strata. ‘agency’ by Benedict Lim cuts to the quick with the sheer injustice of how Malaysians are treated by a hiring agency in Singapore; the hard looks and the voice of an ex-Malaysian provide an extra sting to the story. Elsewhere Tse Hao Guang reassembles poetry in webspeak idiom to render, in a manner both avant garde and strangely colloquial, the mundane obsessions of a “finsta DM” with the “nais face & bodies” of “amoi” and new expressions such as “Convivencia mengfacepalmkan saya”.

Given ancient rivalries, it would be unfair to compare the relative stylistic achievements of Malaysian and Singaporean writers in the anthology. With the exception of ‘Effigies’ by Brandon K. Liew, however, there is a noticeable lack of stylistic inventiveness in the former group, making this volume disproportionately weighted in Singapore’s favour, to some extent. This reviewer wonders if the editors, against their best intentions, could have curated more widely in this regard or considered works in translation.

While new literary works from Malaysia and Singapore continue to be published internationally, The Second Link remains unique and important not only for the time period it foregrounds but also for the deep sense of critique it brings to memorialising the post-independence years. Unlike the focus on empire and the larger Chinese diaspora in novels by Tan Twan Eng and Tash Aw, the anthology trains its sights squarely on the individual lives and experiences that emerge from the myriad hopes and disappointments of nation formation, as well as the frisson of possible futurities now foreclosed. In terms of a commitment to realism and its attendant responsibilities to historical fact, the realist fictions of The Second Link bear comparison with Breaking the Tongue by Vyvanne Loh and State of Emergency by Jeremy Tiang; they evince a granularity of vision and affect that is missing from ambitious works such as The Great Reclamation by Rachel Heng.

Compared to the single-author work, the advantage of the anthology as a form is its continual challenge to read across entries in a comparative and critical mode, thus allowing for the inclusion of sentiments and perspectives that escape the possible myopia of a single ethnic or national perspective. Certainly the kind of historicising on offer in The Second Link refuses the easy nostalgia very much in vogue in the vintage trade prevalent on both sides of the Causeway. Instead, this new volume invites Malaysians and Singaporeans; Malaysians-turned-Singaporean or vice versa and anyone interested in Southeast Asia to consider reflexively the disparate and complex inheritance of borders and how they inform our cultural psyche in the present.

![]()