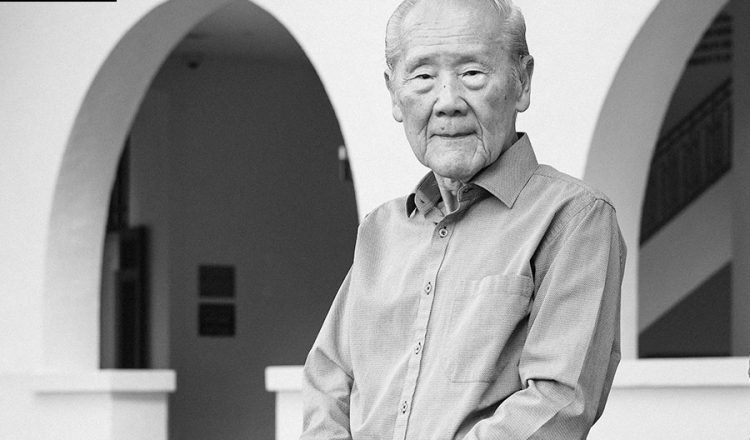

Wang Gungwu finds himself thinking a lot about the little accidents and strokes of luck that have helped him through life. His story is not unusual for an overseas Chinese living in Southeast Asia, but as a scholar and historian he has been preoccupied with the success of the region’s largest migrant community. Few academics in Southeast Asia have ranged as far or thought as deeply about China, the history of its people and its influence on the region.

Wang’s academic career includes stints at the Australian National University; the University of Hong Kong, where he served as vice chancellor for a decade from the mid-1980s; and the National University of Singapore, where he was among the first batches of undergraduates after the university opened in 1949. At the end of October last year, he retired as chair of the board of Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, a position he held since 2002.

Wang was born in Surabaya in 1930 and spent his childhood in Ipoh, which was then part of colonial Malaya. The son of a Chinese schoolteacher who had been sent from China to teach in a Chinese-medium school, Wang went to study in Nanjing on the eve of the communist takeover. He arrived in China in late 1947, as the nationalist government was falling apart. Seeing China as a failing state left an indelible impression on him. Neither he nor his parents ever considered moving back.

Wang was lucky in that his father had taught him classical Chinese as a boy. During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, he stacked English books for his father, who was working as a humble librarian to evade suspicion of being hostile to the Japanese. Wang read many of the books he stacked and so learnt enough English to go on to graduate from an English-language school, which helped him gain entry to the newly established University of Malaya in Singapore.

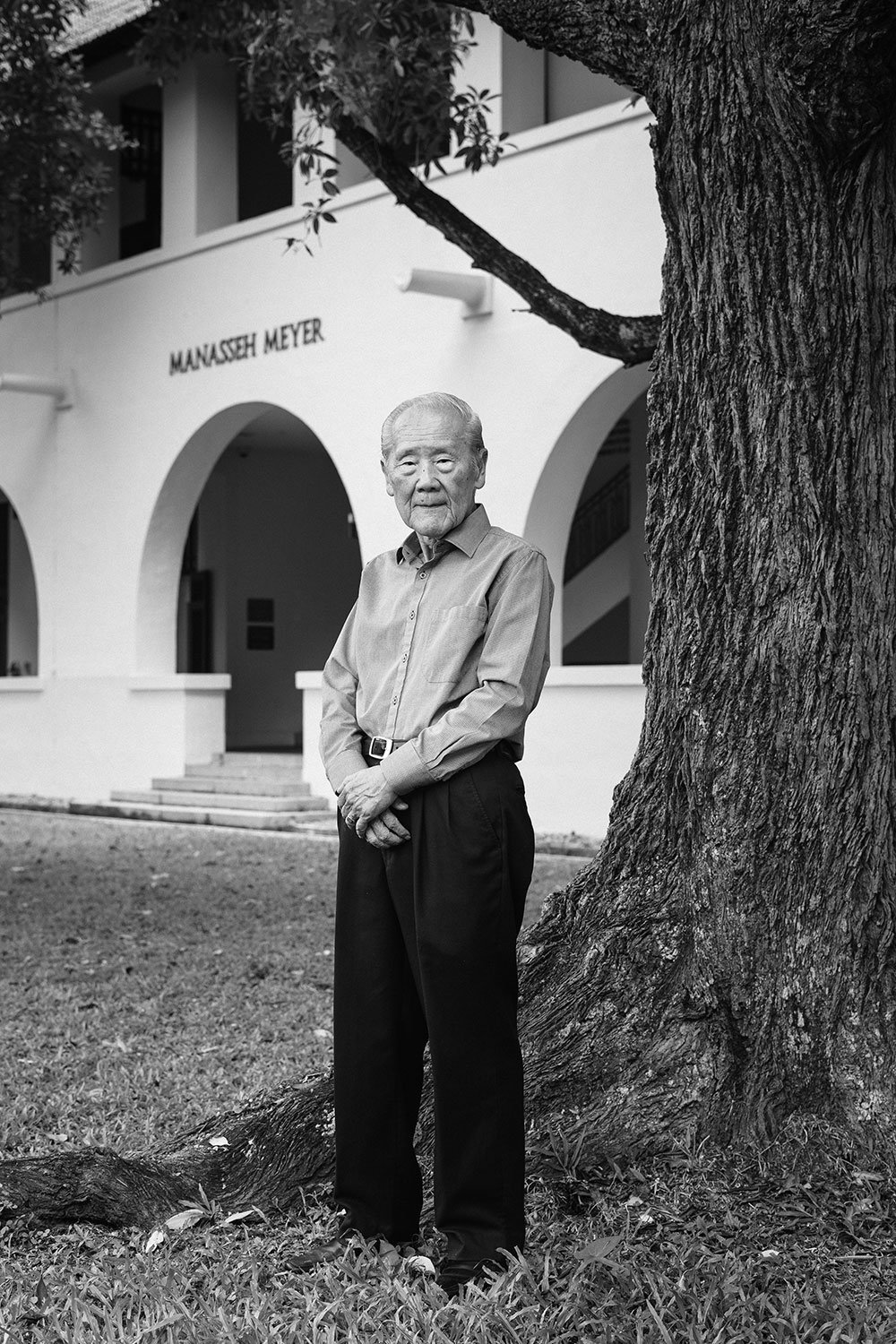

When I met Wang at his office in the stately old campus of the National University of Singapore, off Bukit Timah Road, in the same building he frequented as a student, I found the eighty-nine-year-old in an expansive mood and sipping a milky coffee.

What are your memories of growing up in colonial Malaya?

I remember how diverse the communities were. The teachers and kids at the English school all came from different societies. There was no majoritarian outlook. Even the British — there were so few of them. This is important, because when we say we are all colonials, there are differences. The Singaporeans and Penang people really did live under British rule, whereas people in Ipoh lived under indirect rule. My state sovereign was the Sultan of Perak; the British were advisers on his behalf. In our school, for example, every year we celebrated the sultan’s birthday. When we had events and ceremonies at the school, the sultan or one of his representatives was always present — not an Englishman. The British did all the work, of course.

When I look back, I met very few Englishmen during the seventeen years I lived in Ipoh. A couple of headmasters and a couple of officials — I would occasionally see them in the distance. I knew they were around. But the people I associated with were Indians, Ceylonese, Bengalis, Sikhs and then Malays and varieties of Chinese. Even the Chinese were diverse. The Peranakan Chinese working for the British as clerks, they spoke Malay and English. The Chinese in town spoke Cantonese and Hakka. And here was I, because my father was an inspector of Chinese schools, living in a compound for civil servants. None of them were British (it was the non-British cantonment), but there was just about every variety of Asian you can think of. In the town, almost everyone was Chinese; in the villages, Malay. The British lived elsewhere.

This diversity of the broader population was the norm for me, as was the diversity of the Chinese. Each of these groups had its own exclusive associations. Because my parents were not Cantonese, not Hakka, not Hokkien, we didn’t belong to any of them. My parents came from the Mandarin-speaking part of China. So, for the first ten years of my life, until the Japanese came, I was isolated. My family were outsiders, just there temporarily and preparing for a transition home.

When you went back to China it must have been quite strange for you.

In 1947, the year we left Malaya, there was much uncertainty. The newspapers said that the Kuomintang [the Chinese nationalist party] was winning and that the communists were losing, but that’s not what the people believed. The nationalist press reported their side’s victories but not the defeats. So for the first year we didn’t realise how serious it was, but by the middle of 1948 it was quite clear. The economy collapsed, and the yuan took off like the German mark after World War I.

I was the richest boy on campus, because my father sent me fifteen Hong Kong dollars a month. My uncle told me to change only one dollar at a time. Every time I changed a dollar I would get a stack of worthless currency in big bags. I would bring a bag along to buy a bowl of noodles. The vendors didn’t even want to count it, preferring to weigh it instead.

It was a failed state if ever there was one. My first contact with China was to see it failing before my eyes, which had a traumatic effect on my world view.

When you left China in 1948, did you feel you might go back again?

I never thought about it. My uncle had bought me a ticket on a Butterfield & Swire boat from Shanghai to Hong Kong. Once I [returned to Malaya] it hit me that the communists were taking over China. My parents had no intention of going back to what would soon be a communist country. To them the communist victory was a tragedy. They had accepted the nationalist propaganda of the time — that these communists were indoctrinated with a foreign ideology. Communism was a Soviet Russian import. What are we Chinese doing following Stalin? This concept was totally alien to my father. Dealing with the British was difficult enough, but at least they had been around for a hundred years or so. Dealing with the Japanese was hateful, but you knew they were the enemy. But who were these Russians? Who was Stalin? Who were [these] bearded guys? What have they got to do with us Chinese? So from my father’s point of view that was it. The China that he knew was gone. My parents had no intention of celebrating this new China.

Wang has written extensively about Chinese history and civilisation. Of late, these scholarly reflections have gained saliency because of China’s rise and impinging influence on Southeast Asia. Unlike many of the Western scholars who approach the subject, Wang is unaffected by binary perceptions of civilisation and ideology. He considers assumptions about overseas Chinese assimilation in Southeast Asia, for example, to be exaggerated and rooted in American melting-pot idealism.

In his latest book, China Reconnects: Joining a Deep-Rooted Past to a New World Order, Wang considers the ways that China is adapting to its growing role in global political and economic affairs. His thesis is not what you might expect; there are no dreamy assumptions of convergence with Western notions of democracy. Rather, he argues that China’s integration into the modern world will depend on the country’s recovery of its past.

Yet Wang is no apologist. As his views on the current troubles in Hong Kong indicate, he believes that a strong sense of identity will make it hard for China to prevail in Hong Kong. His deep knowledge of the history, going back to the aftermath of the Opium Wars, centres on a strong sense of coastal independence that originated in Shanghai, after it was established as a treaty port, and then transferred to Hong Kong after 1949.

During the height of the Cold War many Chinese subjugated their identity. But over time opportunities arose in China and there was reason to be proud to be Chinese.

I never quite bought the assimilation argument. The Peranakan Chinese were in fact forced by the Kuomintang to rethink their Chinese identity. They felt embarrassed about not knowing Chinese — that’s another link to my story. My wife’s mother came out to teach Peranakan Chinese students. They set up a school in Singapore: a Chinese school for Chinese students who didn’t yet speak Chinese.

I suspect this whole notion of assimilation was due to the American melting-pot theory: the Americans hoped that everyone would become American. They said these nations in Southeast Asia would do the same. But it wasn’t the same, and the British knew it. The British, the French, the Dutch — they had already been nation states, for at least one or two hundred years. The Americans were new; they were a bunch of migrants. They thought that a migrant society would assimilate migrants, but they forgot that the Chinese were going into new nation states whose citizens had been trained to think like the Dutch and the British and the French, not like the Americans at all.

If we look at the contemporary period there are huge opportunities in the motherland for the overseas Chinese.

Overseas Chinese have always been able to pursue opportunities, but now they can do so more easily, with people who actually think like them. They are not so communist anymore; they are now capitalists. Before 1949 — in fact, before the Great Leap Forward — all Chinese thought like capitalists, even in China, so relations were still all right. The Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution were followed by a twenty-year break. After a rocky start under Deng Xiaoping, Chinese capitalists once again understand each other. The entrepreneurial instincts of the Chinese have been restored to their former glory.

Now that we are seeing an assertion of China, what does that mean for the societies here?

It varies tremendously from country to country. The most positive sides of it are economic integration and shared prosperity. That’s what the Chinese think — that China has lifted up its citizens and that the connections in Southeast Asia will do the same across the region. I don’t think anybody would object to that in itself. Things are complicated, however, because the Americans see this part of the world as part of their hegemony. They don’t want the Chinese to remove them from, as they see it, their rightful position here. If Southeast Asian countries continue to integrate economically with China, the Americans will be pushed out. This is not just a trade war; it is about who is the hegemon. The Americans say that they are the hegemon and that the Chinese are a threat. I think this is the source of all our problems.

So China’s rise is no longer in America’s interest?

That’s right. That sums it up.

On Hong Kong — why aren’t Hongkongers interested in the China Dream? What is the Hong Kong identity?

The Hong Kong identity emerged in the 1980s. It was already in place when I went to Hong Kong University in 1986. I traced it back to the Cultural Revolution. The people of Hong Kong actively responded to the revolution by dividing into two: one group became Hongkongers; the other group said Hong Kong belongs to China. The idea of a Hongkonger is not dissimilar to the idea of a Shanghainese in the treaty ports. In a way, Hong Kong was the last treaty port. It was called a colony, but that is deceptive. It was never a colony in that sense: it was a bunch of British businessmen using the place as a merchant base for dealing with China, but 95 per cent of the population was always Chinese. And they were always connected with China and Chinese politics — nationalists and communists alike used Hong Kong, and the British, who managed the place for their own purposes, knew that. It was a treaty port in everything but name.

In practice, though, Hong Kong was never the biggest of the treaty ports — Shanghai was. After 1949, Shanghai came to Hong Kong. That’s what it boils down to. And, since the treaty-port era, the Shanghainese have always had a very strong sense of identity. You can come from any part of China originally, but after one generation in Shanghai you are Shanghainese and proud. The Shanghai identity localised itself with the Cantonese, too. Don’t forget that even in Shanghai the leading people were often Cantonese.

So what defines the Hong Kong struggle today?

It’s an internal Chinese struggle. But because the young people have no one to turn to, they appeal to Trump and others. It really began when Deng Xiaoping opened up China in the 1980s and developed industry — all the Hong Kong industries migrated north. Shenzhen opened up, it was much cheaper and it welcomed the Hong Kong capitalists. Why employ expensive Hong Kong labour when you can get it at half the price? That was well before 1997.

The astonishing inequality in Hong Kong today stems from this?

It stems from the origins of the free-port idea. The government had limited sources of revenue. Well before modern times, some clever officials had worked out that selling land was a guaranteed source of revenue; when there’s a shortage of land to build on, prices rise quickly. So they sold small parcels of land at very high prices. But the developers built expensive housing only. And if land was set aside for public housing there was even less land to sell. So a lot of tension developed out of this raising of reliable regular revenue, starting with opium farming and then sales of land. Meanwhile, as China develops, more money enters the property market. And so all the prices went up. Even if the government changed its policy it would take a long time to work. I don’t think the young people can wait that long.

These young people in Hong Kong, they have nothing to lose?

They have been led to think that. The democrats before them, the former leaders they admired, they have made concessions and can no longer be counted on. It’s these older-generation political leaders who have nothing to lose, because they’ll be gone by 2047, when Hong Kong is set to lose its special autonomy status. Most of today’s protesters will still be relatively young. To live in just another Chinese city — to them it’s not the same. As a result they have no leaders.

So where does this lead? What happens?

The pro-democracy movement now has a few hundred people elected to district councils. In the seventeen councils in which they dominate, the elected could form a group and choose a spokesperson to represent them in meetings with Carrie Lam [the chief executive of Hong Kong] and her team. This is theoretically possible, but I don’t know whether it would work. After what the protesters have been through in the recent months, they probably feel that this would be giving up.

How would Beijing view this?

Beijing wants to avoid direct intervention — that’s obvious. They just say that “one country, two systems” is the Hong Kong system. The Hong Kong people must work it out for themselves. If they want advice Beijing will give it, but the Chinese system is not the answer.. I don’t think the central government in Beijing has any choice.

Isn’t the Beijing leadership ultimately responsible for this mess?

They are not responsible. The extradition law was initiated by Carrie Lam and her people. She was not alone: she was backed by smart lawyers. They believed that by having an extradition law they would avoid people being kidnapped, being taken without legal process, which had been happening and generating bad publicity. The law was carefully worded; they had decided that the ultimate decision on extraditions would be left in the hands of Hong Kong’s judges. If there was no case for extradition, no one would be sent back. But it was not the wording of the law that mattered. It was the timing — the people who had led the Umbrella Movement and occupied central Hong Kong for little gain didn’t want to make the same mistake and give in too easily.

Wouldn’t it make sense for China to appoint an envoy to Hong Kong?

I don’t think they would do this publicly. They genuinely want to preserve one country, two systems. The least they can do is keep on talking about the future of Hong Kong, and now they have some people to talk to. The pro-democracy candidates elected to district councils — they are legitimate. I think they are reaching out.

Do you see Xi Jinping’s hard ideological line as a long-term certainty?

It’s not a sign of Xi Jinping’s great power but rather a sign of the need for security to protect his position. He has no faction himself, so he depends on a group of younger people loyal to the ideas he represents. He’s gathering others who accept him. But these are defensive positions: he has enemies galore. After this anti-corruption campaign they must have added up, and that will continue. People accept Xi because, first, they have no choice and, second, his policies have been really popular with ordinary folks, who are still doing well economically. But a large proportion of the highly educated are unhappy. That’s evident, but there’s no alternative to Xi at this stage. That remains a tension.

Despite China’s brittle leadership, are you optimistic about its decisions to become involved overseas?

In my latest book I argue that the Chinese are confident and that they are what I call “reconnecting”. What they have needed since the Deng Xiaoping reforms is to overcome the terrible Mao period, and the awful years before that, and to connect to the past — because Mao rejected all that. China has reached that point. Until recently Mao himself was rejected to such an extent that to mention Marx you would be laughed at. That won’t do, because if you don’t look at Marx, you’ll have to look at George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, but they have no continuity in China. Once you recognise Marx as a sage — the other sage, as it were [the first one being Confucius] — you can connect the Cultural Revolution, the Great Leap Forward and the nationalist era, all the way back to the Manchu Qing. The confidence to reconnect as such was missing under Hu Jintao and others, but Xi Jinping has a group of young people who share that confidence.

What is the best coping mechanism for Southeast Asia in the new environment of rising competition between the United States and China?

It is in everyone’s interest for the ten ASEAN countries to stay united. Both the United States and China would like to keep the association together and have it lean in a certain direction; if each side thinks the other is trying divide ASEAN, Southeast Asia will suffer in the long term.

![]()

- Tags: Issue 18, Malaysia, Michael Vatikiotis, Wang Gungwu