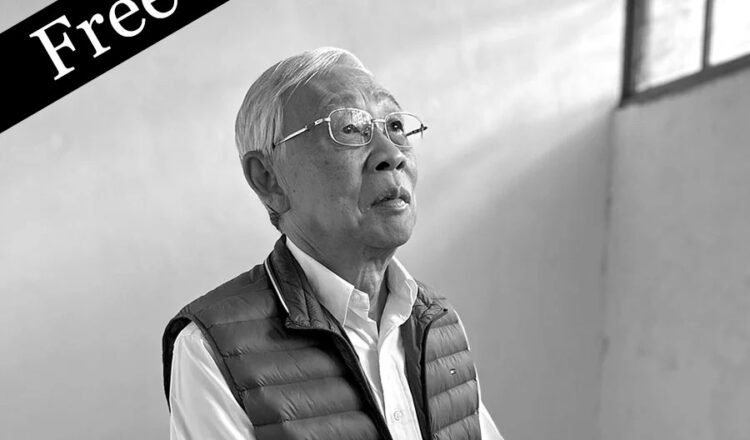

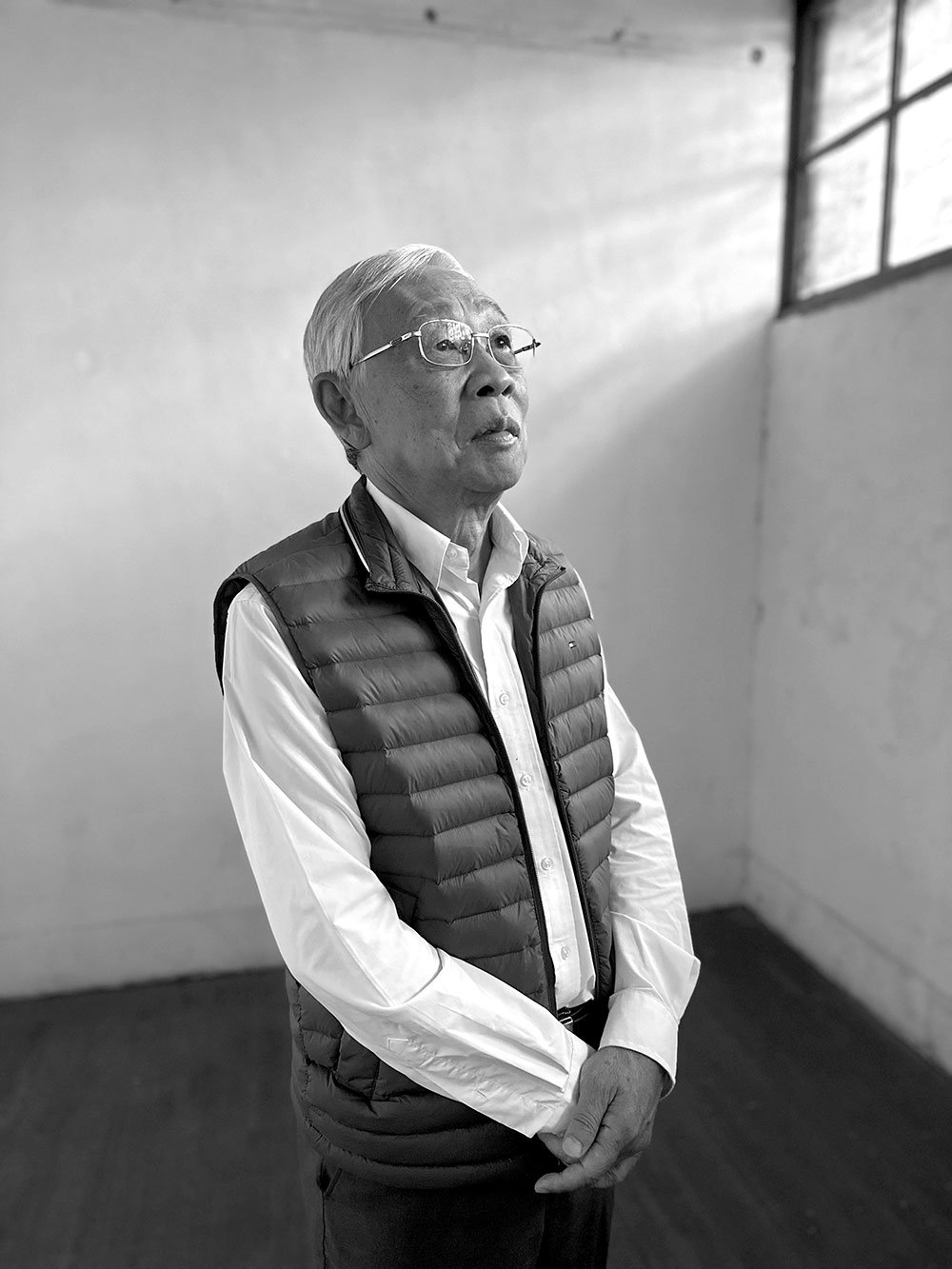

When we meet at the Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park in Taipei, it doesn’t take long for Fred Chin to start detailing the arrest, interrogation, and torture he endured as a political prisoner during Taiwan’s White Terror era.

It’s a story the seventy-six-year-old has told hundreds of times, to thousands of people, in the fifteen-or-so years he’s been giving tours at the memorial park, established on the site of the detention centre where he’d been imprisoned for the first part of a twelve-year sentence.

Chin, then a twenty-one-year-old chemical engineering student from Malaysia, was arrested in the early 1970s after a bomb exploded at the US Information Service in Tainan, where he’d spent time perusing reference materials. From his initial arrest to horrific torture at the hands of the Kuomintang’s security officers, Chin had no idea why he’d been accused of involvement in the bombing. But he’d quickly realised that, once taken into custody, his conviction and imprisonment was a foregone conclusion.

During our conversation, Chin kept reiterating that his story is as much a firsthand account of a dark time in Taiwan’s history as it is a cautionary tale of the sadism and cruelty that can manifest when authoritarianism runs rampant and unchecked. At a time when more and more countries around the world seem to be embracing authoritarian tendencies, Chin’s experience is a glaring reminder of the horrors that such systems can breed.

Our interview went on for a long time and Chin went into plenty of detail about his experiences. The following transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

You were born in Malaysia. What brought you to Taiwan, and how did you get arrested?

I was born in the year 1949. In 1967, as a student, I came to Taiwan without knowing that Taiwan is a Mandarin-speaking country. Back home in Malaysia, I was English-educated. I couldn’t understand much Chinese, especially Mandarin, so when I arrived I was confused and a little shocked. I wanted to go back, but had no budget. So I told myself I would have to stay, since I made the choice to come to Taiwan.

Because I couldn’t catch up with my schoolwork, I had to refer to the original textbooks, so I went to the office set up by the US government, the US Information Service [in Tainan]. Almost every single day I was there, because I had to find a convenient, comfortable environment for me to study.

Unfortunately, in the year 1970, there was a minor explosion that happened in that location. I knew nothing about it, but I was targeted in 1971. A man came to me, saying that I had a relative from Malaysia who was now in Taipei. He said [my relative would] be going home early in the morning and had called to ask him to locate me and bring me to Taipei so we could meet. I didn’t suspect anything. But when I got in the car, I realised the story wasn’t what he’d told me.

Once in Taipei, I was put into a small room for about two weeks. They asked me to confess, to write down what I’d done. But I didn’t know what they really wanted from me, so I couldn’t write a single word. I think, for about eight to fifteen hours [a day]—we call that round-the-clock interrogation—I wasn’t allowed to go to the toilet, I wasn’t allowed to have food or drink. I wasn’t allowed to sleep, either. It wore me out—but I still couldn’t write a single word.

I knelt and begged them to tell me what had happened, what they wanted from me. “Please let me know, I can’t endure anymore, the torture from you. The pain, the humiliation, the pressure from you. So please let me know, I’d like to end the pressure and the pain.” But they said, “No, we can’t tell you anything, you have to confess all by yourself to show your sincerity.” I didn’t know how to face that, so I just sat down. They weren’t happy with me.

They punched me, kicked me. I threw up blood. They were furious. They said, “You dirtied our carpet, you have to clean it.” They wouldn’t offer me a cleaning cloth or anything like that. The officer pressed my head down, pushing my mouth into the blood.

Later, two men tied up both my legs and my hands behind my back. I was hung upside down. You can immediately feel the pressure, the blood rushing to your brain. It’s really suffocating. They covered my mouth with a wet cloth and pumped water into my mouth with a long tube. I don’t know how to explain [how it felt] to you. I really hate those guys—those two guys, I really hate them.

I thought I’d rather die than stay alive. I did try to die, but it didn’t work. Later, a man held my hand and pressed a needle under my fingernails. That was the most painful experience I’ve ever had in my life. I was totally paralysed by the pain. Those two weeks were the most horrible of my life.

What happened after that?

They got my confession after about two to four weeks. They wrote down what they wanted and used those documents to indict me. After indictment, my trial began. The judge asked a lot of questions, then suddenly said, “We are going to pronounce your verdict.” He said that I’d done something against the Republic of China, but he wasn’t going to punish me with death. Instead, he sentenced me to twelve years.

Once I heard that I was to be punished with twelve long years, I raised my head and said, “Your Honour, I have questions.”

He stared at me and said, “We didn’t punish you with death, you should be happy, you should be appreciative. Why are you not happy?”

I said, “Sir, you are totally wrong. The reason you used to punish me is totally untrue, all falsified. I’ve done nothing. You should release me instead of punishing me with twelve long years.” I added that “if you can’t release me, since you indicted me for rebellion, please punish me with death”. I didn’t want to stay in jail for twelve years.

Suddenly, the judge stood, walked down, and murmured something incredible in my ear. He said, “It wasn’t me who wanted to punish you to twelve long years. If I didn’t announce it accordingly, the next one on trial might be me.”

At that time, the trials were totally closed-door. Not a single word would make it to the outside world, so they could say anything they wanted. Those people—no matter if they’re the presiding judge, the court-appointed lawyer, or the prosecutor—they’re all the same group of people. Today you might be the judge, the next day you might be the prosecutor. I learnt that they were powerless, that they couldn’t finalise any of the cases. All the verdicts the judges wrote were sent to the president, for President [Chiang Kai-shek] to look over. Many people were killed, executed because of him. If he wasn’t happy with my verdict, he could have just picked up his pen and written something and I’d have ended up in the execution yard.

This is why I want to share my story. Since I was here [at the detention centre] about fifty years ago, I’ve learnt so many stories like this. I want to share my story with the public so they can understand how ridiculous it was during that time. We want to stop these things from happening again.

You were a Malaysian citizen at the time of your arrest. What was the Malaysian government’s reaction?

The Malaysian government learnt that I’d been arrested and sent an immigration officer to pay me a visit. I never got the chance to see him. I don’t know why he was rejected. They told me that the immigration officer would be coming to see me, asked me to dress up and wait for the call, but the call never came.

A year or two ago, I went back to Malaysia and met the guy. The immigration officer, he was still alive. He told me that he didn’t know much. He’d just waited for the notice [from the Taiwanese authorities]… and waited and waited and waited until the office was closing and he had to leave. He resigned not long after; he didn’t want to stay in Taiwan.

Apart from Jing-Mei, you were also detained on Green Island, a penal colony for political prisoners off the eastern coast of Taiwan. What was that like?

[The other prisoners] were more optimistic than me. They played games, played chess. They talked, they exercised, they read books and wrote. They were very, very good to me. I was pessimistically sitting in a corner, speaking to no one, sharing nothing. They came, one after another, and sat in front of me, trying to help me change my mindset, to accept the things that we couldn’t change.

One day, when I was forced to go out for exercise, I just collapsed. But the advice they’d given me came to me. I told myself, If I die here, my sacrifice will have meant nothing. I should keep myself strong so that one day I’ll have the opportunity to share my story with the world. To tell them how badly I was treated. From that day onwards, I tried to pick myself up. I tried to pick up experiences. I learnt a lot in the library; that was the first job I had [as a prisoner]. I picked up so many words, I learnt Mandarin. My last job was in the kitchen. I learnt a lot of recipes; I can cook well. [The other prisoners] told me that this was good; if I’m back in society, this might be what I depend on to earn a living. They taught me well, so I can cook pretty well.

You were finally released in March 1983. What was that like?

On the day of my release, I asked for deportation back to Malaysia. They said, “No, we can’t let you go.” The Malaysian immigration officer, together with my youngest brother, came to Taiwan with a permit that would allow me to return to Malaysia. But the Taiwanese security office said, “No, we can’t let you go because you know too much about Taiwan.”

I even applied for political asylum to Canada, and it was approved, but Canada wanted me to go to Hong Kong. They couldn’t pick me up [directly from] Taiwan. But I couldn’t leave, I didn’t have a way to get out of Taiwan.

I argued with the [Taiwanese authorities]: “You say that I know too much about Taiwan. But how could I know anything about Taiwan? Two-and-a-half years of school life, twelve years in prison—what do I know about Taiwan?” But I couldn’t win the argument.

They said they would offer me Taiwanese identification, because during the martial law era, you couldn’t go anywhere without identification. They wanted me to find a job, get a place to stay. But nothing happened, so I ended up homeless for three long years. It was a sad life. Homeless life is much worse than life in prison. You know that you’re free, but you can’t do anything, you can’t see any future.

I finally managed to get identification after three long years. Then martial law was lifted in 1987.

You’ve been giving regular tours at the Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park for some time now. I’d have thought that this would be the last place you’d want to come back to. Why do you still return?

Many people ask me this question. They say, “If I were you, I’d never, ever come back here. I’d leave this place, stay far, far away!”

I tell myself that, as a human being, this is something good for me. I have to do something. I got my future back, I got my life back, I got my every happiness back. Many from the younger generation in Taiwan have been trying to learn about the past. And many of the older political prisoners—they’re over eighty or ninety—are still stepping up to share their stories publicly. I told myself that I have to do something because I’m the youngest [among these prisoners].

Do you find it traumatising, though, to tell these stories over and over again?

Of course! In the beginning, yes. It was difficult for me to step up to record the memory that’d long been hidden in my mind. After the first speech I gave, for about two or three weeks, I couldn’t sleep well. The nightmares continued to strike me.

After that, I calmed down a little bit, and someone else came to tell me that they wanted me to say more. I shared my story each time. The second time… how do I say this… it was hurting in my mind. But gradually I found that each time I tried to share my story honestly with the younger generation, the huge encouragement and energy that they gave us—telling us that we’d overcome all the suffering and all the pain, that we were letting younger Taiwanese learn about the past so that they can protect themselves in the future. If they didn’t know about the past, about what happened to us, they wouldn’t understand what they enjoy today. So these tragedies might reoccur any time. We have to get more people to learn to support themselves, to fight for the future.

When the National Human Rights Museum Preparatory Office was set up in 2011, about twenty to thirty of us [former political prisoners] came to help. There was nothing, so we helped to gather a lot of artefacts, a lot of documents, a lot of stories, oral history, that sort of thing. We did a good job, honestly speaking, the twenty or thirty of us. Today, most of them are gone, so I feel a little bit lonely when I step in here, now that I can’t see other former political prisoners walking around. But anyway, I tell myself that I promised those seniors, those political prisoners, that I’ll continue to do the job. That’s why I’m here.

It’s been more than half a century since your arrest. In recent years, we’ve seen a rise in authoritarianism across the world. How does that make you feel?

I’m really worried about it, because we’ve been doing so much, but the world doesn’t seem [to be developing] like how we expected it to. It’s going down instead of upwards.

To me, we can’t do anything about that except stay firm, continue to share our stories, to get more people to understand what we’re trying to protect in the world. That we’re trying to protect the rights of every single person.

The only thing we can do is to continue: to organise, to let more and more people learn what we really want the world to be. We can try to tell them, “[Under authoritarianism] the world would be like this.” We try to be clear so they can absorb the information. We let them understand that if you go the wrong way, you’ll suffer. If you understand us, you’ll be on our side.

Do you ever worry that the message isn’t getting through?

Yes, this is what I’m really worried about. In the US and many, many other countries, they’re becoming really anti-immigrant. I don’t know why the world is going down instead of up. I worry about it. Even in Taiwan, [there are politicians] trying to create a certain kind of chaos, a kind of hatred among the population. Maybe we can’t stop them. This is what I’m really worried about.

But I still have a certain kind of belief that the positive will overcome the pessimism, the negative feelings. I tell myself that I will continue to do whatever is needed. I try to share my story. I tell myself that, if I can make one more person understand me, that person will stand on my side.

![]()

- Tags: Calum Stuart, Fred Chin, Issue 42, Taiwan