Eikoh Hosoe

Yasufumi Nakamori (editor)

MACK: 2021

.

The birth of butoh, a wildly creative Japanese art form commonly described as the ‘dance of darkness’, can be traced back to a notorious performance staged in Tokyo in May 1959. Titled ‘Forbidden Colours’ after a Yukio Mishima novel of the same name, the much-mythologised routine featured the dancers Tatsumi Hijikata and Yoshito Ohno, and left the audience in shock over the fate of a live chicken.

Watching was Eikoh Hosoe, a young Japanese photographer who later recalled that he’d ‘never seen such ferocious dancing’. For Hosoe, it was a seminal encounter—one that would influence the trajectory of his own artistic practice and spark a lifelong collaboration with Hijikata and several other pioneering butoh dancers. While Hosoe was already beginning to inch away from the social-realist photography style that was then dominant in postwar Japan, his chancing across the eccentric Hijikata may have catalysed a turn to the daring, dark and often theatrical images that would set his work apart.

A selection of these images is presented in Eikoh Hosoe, a recent survey of the photographer’s significant body of work, edited by the curator and art historian Yasufumi Nakamori, and with the input of Hosoe himself, who is now eighty-nine. Some of the artist’s key photographic series are included, alongside writings by Hosoe and his contemporary collaborators (novelists, critics, poets and performers, some of whom appeared as photographic subjects in the worlds of Hosoe’s creation over the years). While the images stand alone, the texts offer intriguing snippets of insight into Hosoe’s work and influences, and the impact he had on photography in Japan. Many have been translated from Japanese into English for the first time.

Writing of that formative period for Hosoe in the late 1950s, Nakamori notes that ‘instead of simply photographing a subject, he began to view himself as involved in the collaborative creation of a distinct space and time’. He was not content to passively document what he saw through the lens, but directed and propelled the action, driving himself and his protagonists to draw out every last vestige of creative energy. On one photo shoot, Hosoe worked with such intensity that he temporarily lost vision in the eye that peered through the viewfinder. ‘Similarity is lethal,’ Hosoe said of his practice. ‘I focus my every fibre on doing something no one else has done, working strictly for the joy and pride I find in that.’

Collaboration was central to Hosoe’s avant-garde approach. Alongside Hijikata, Kazuo Ohno, one of the founders of butoh and the father of Yoshito Ohno, was a key presence. Over more than four decades, Hosoe captured the full expressiveness and experimentation of Ohno, his face invariably caked in the ghostly white make-up synonymous with butoh. From the stage to the street, from Ohno’s home garden to a marshland in Hokkaido, Hosoe shot the performer in moments of both quiet poignancy and full-throated expression—almost always in the black and white tones that defined his work. They seemed to feed off each other’s practice. ‘My photographing is part of his dance,’ Hosoe once wrote to the photography historian Carole Naggar. In one distinctive image, a kimono-clad Ohno dances along a rickety wooden pathway, holding a parasol high above his white-painted body, appearing like a spectre in the rural landscape.

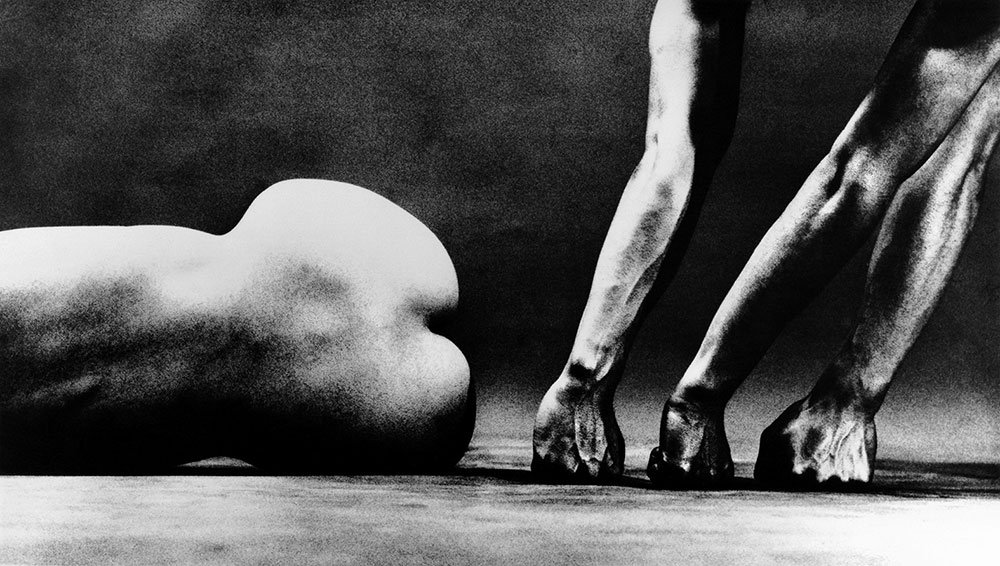

Man and Woman (1959-60), featuring Hijikata and other performers, was Hosoe’s first breakthrough. The series is composed chiefly of grainy black and white shots of human bodies: an elbow meeting pursed lips, three fists pressed into the floor beside a naked torso, and Hijikata’s lithe frame straining against a leaden sky. While photos of the body in black and white may sound completely unremarkable, Hosoe manages to summon a deep emotional charge. The simplicity of the images is part of their power. They are cropped in a way that isolates them from the body as a whole, creating the impression of new vistas: skin like the surface of another planet, a head being carried as if detached or arms that could be elephant trunks. The play of shadows and light would also be a thread in Hosoe’s work.

The series made an impression on Mishima, the prolific and influential Japanese novelist who spectacularly ended his life by ritual seppuku in November 1970, after a shambolic attempt to instigate revolt at a military base in Tokyo. He approached Hosoe almost a decade earlier—shortly after Man and Woman—to photograph him at his elaborate home. Hosoe insisted on taking the photos ‘my own way’, which included wrapping a rubber hose around Mishima’s naked body in a process he described as ‘idol destruction’. In a revealing essay by Hosoe on the shoot, which is included in the book, there is a sense of the photographer testing the limits of his art, and his subject, and he reflects on whether he had gone ‘too far’. He later learned that Mishima’s children were sent away with his wife on the days of the photo shoot as it was considered ‘educationally unsuitable’.

The series would become Ordeal by Roses, and Mishima enthusiastically embraced the outcome. He described the photographer as ‘shrewd as a fox descending the hills to capture a farmhouse chicken’, and admired the ‘undercurrent of darkness’ in his work. The image of Mishima staring intensely into the lens, with a rose covering his mouth, is one of the best known from this series, but also one of its least experimental. In several others, Mishima’s body blends with Renaissance art works and objects, so that he appears like a flickering presence within layers of images. After Mishima’s suicide, Hosoe was mindful that his photos not be ripped from their context and contribute to (further) sensationalising the incident. A new published edition of Ordeal by Roses was delayed until Mishima’s widow expressly asked that it proceed.

During this period, in the 1960s, radical politics, mass protests and avant-garde art were all taking off in Japan, against a backdrop of rapid economic change and widespread dissatisfaction with the postwar status quo. Mass mobilisations took place against the renewal of the country’s security treaty with the United States in 1960, forcing the resignation of Nobusuke Kishi, the prime minister. Hosoe’s work embraced the experimentation and transgression of this era. At a time of ongoing migration from Japan’s rural communities to the cities, Hosoe explored themes and settings of rural life in his work, most notably in Kamaitachi (1965), a series featuring Hijikata and shot in the dancer’s home prefecture of Akita, northwest Japan.

In Kamaitachi, named after the weasel-like creature in Japanese folklore that is said to ride whirlwinds, Hijikata is depicted in constant motion, tearing through the rural landscape, inserting himself among bemused locals and causing general disruption. In one image, he sprints through a paddy field holding a screaming child. In another, he leaps through the air, his white kimono billowing out, as a group of children regard him with quiet curiosity. In a village, an elderly local holds a magnifying glass up to his face, as if inspecting whether this strange presence is real or apparition.

Hosoe, who grew up in Tokyo but was evacuated to the countryside during the war, saw the shoot as an opportunity to explore his childhood memories of that time, as well as to capture Hijikata far away from the conventional stage. As with much of Hosoe’s work, the series was a genuine collaboration, dependent on his direction and skill, as well as Hijikata’s raw creative dynamism as a performer. Such was the uproar created by their sudden, manic appearance in the village that, more than twenty-five years later, Hosoe returned there to apologise. To his relief, upon his arrival he was met by locals with homemade pickles and a banner that proudly stated: ‘Greetings Photographer Hosoe. Welcome to the Home of the Kamaitachi’.

Hosoe is credited with transforming attitudes toward photography in postwar Japan and bringing the practice into the domain of experimental art. Artistically and intellectually, Nakamori states, ‘he helped free the medium of its insular past’. Hosoe’s contribution was also practical: during his career he taught photography, helped establish several galleries and was an active advocate for photographers’ artistic rights. Eikoh Hosoe is a beautifully presented record of his work.

![]()

- Tags: David Hopkins, Eikoh Hosoe, Issue 27, Japan, Yasufumi Nakamori