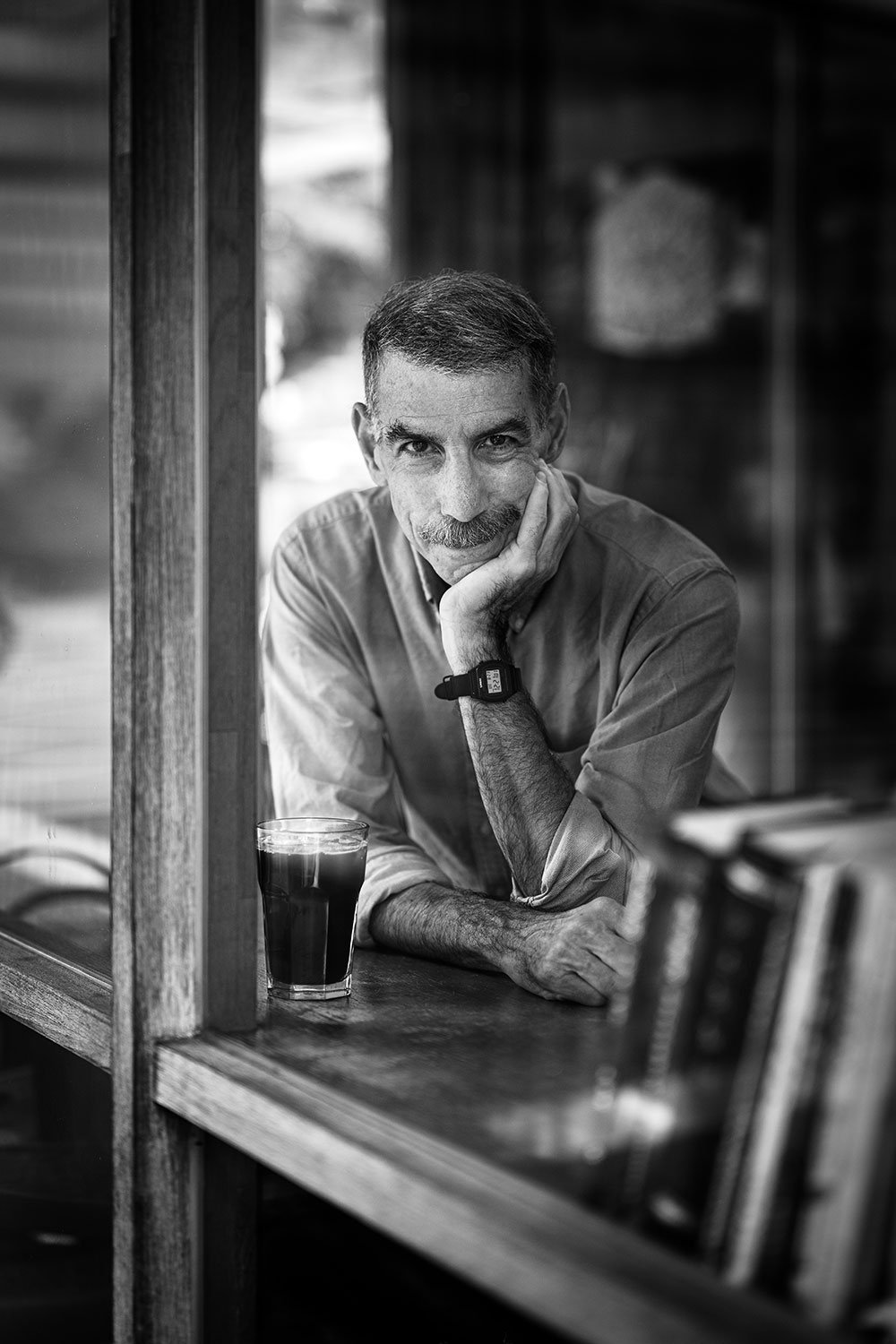

I find Mike Chinoy, who has been a journalist in Asia for almost half a century, sitting at a coffee shop in one of Taipei’s most generic shopping malls. Through the 1980s and 1990s, Chinoy was the face of Asian news on CNN and first on the scene for many of that era’s biggest stories. He filed the first TV news report for American television on the Tiananmen protests of 1989 and was the first to go live from North Korea. (In all, he made seventeen trips to the hermit kingdom and remembers, with a grimace, the ‘Great Leader’, , cracking jokes about shooting bears over dinner.) He also snuck into Afghanistan to interview the Mujahideen and covered everything from the Philippines People Power protests to the first Gulf War.

The former reporter’s trademark moustache and hair are now silvery but still camera perfect. With a glass of lemon tea and a beat-up MacBook in front of him, he is tapping away on an edit of a new documentary about the Taiwanese decathlete Yang Chuan-kwang, whom he describes as “the first person with a Han surname to win an Olympic medal”.

“You know, maybe it’s all those years of staying in hotels, but I find I do my best work in coffee shops,” Chinoy tells me. “It’s much easier for me than working at home. And for what I’m doing now, as long as there’s internet, it doesn’t really matter where I am.”

A native of Northampton, Massachusetts, Chinoy has been in Taipei since early 2022. For the past fifty years, his main bases have been Hong Kong, where he started out as a stringer for CBS radio in 1976, and Beijing, where he opened CNN’s first Asia bureau in 1987.

After leaving CNN in 2006, Chinoy moved on from three-minute news pieces to the long-form narratives of books and documentaries. “I don’t miss the phone calls at three in the morning telling me I’ve got to pack my bags to go cover some awful tragedy in some hellhole,” he quips. In his latest book, Assignment China: An Oral History of American Journalists in the People’s Republic, he’s taken on the role of a meta-journalist, examining how reporting in China has been done, packaged and delivered to the public. The volume collects more than eighty years of journalist stories, from the maverick correspondents of the 1940s, who shuttled between armies during China’s civil war, to the Wall Street Journal’s recent disclosures of the secret fortunes of the Communist Party leadership. It’s a treasure trove for any news junkie; most fascinating perhaps are how some of the biggest stories—including the famous photo of Tiananmen’s “tank man”—almost never made it to press.

While Chinoy and I discuss his book and career, it becomes apparent how deeply the two are intertwined.

You’ve been reporting on China since 1976 and have spent thirty-seven years based in Hong Kong or Beijing. How did you first get interested in China?

I was part of the Vietnam War generation and got interested in China because the official justification for the war in Vietnam was to stop the spread of communism in Asia. The Chinese were portrayed as the bad guys. As somebody who was against the war, I wanted to learn more about China. That’s what sparked my interest.

I was able to make my first trip to China in 1973 through a left-wing newspaper in New York called The Guardian—no relationship to the British Guardian—that had been set up in the 1950s and been sort of a friend of China. After Nixon, they got into the business of organising friendship tours, so I was able to go on this trip for a month in the summer of 1973. We were one of the very earliest groups in. We went to Guangzhou, Shanghai, Beijing and northeast China. It was like the automobile, steel mill, coal mine tour.

What impression did that 1973 tour leave on you?

As somebody who had just graduated from college and wanted to be a foreign correspondent, it really solidified my interest in getting back to China. This was before Americans could study in China or easily visit as tourists, so being a journalist offered one of the few avenues to get back there. That really was the central reason why I decided to be a journalist. I got interested in journalism because I was interested in China, not the other way around.

China had actually been closed to journalists for more than two decades after 1949, with the door only opening slightly in 1971. How did journalists view the prospect of getting back into China as access slowly became possible in the 1970s?

There was this attraction back then. Barbara Walters told me that when going to China with Nixon, she felt it was like going to the moon. There was this sense of exploring unknown, forbidden, mysterious territory. China had been essentially inaccessible to Americans for a quarter century. There was obviously just the appeal of the unknown, if we want to be honest about it.

How did you get your start covering China?

After I got my master’s from Columbia’s journalism school, I got a fellowship through them. But they were running out of money, so they just gave me a one-way ticket to Hong Kong and said, “Good luck.”

My first job was as the radio stringer in the CBS Hong Kong bureau, and I was paid US$35 for each radio spot used. I arrived in Hong Kong on New Year’s Eve 1975, and then in rapid succession: Zhou Enlai died; there was the first Tiananmen Square riot, in which Deng Xiaoping was ousted by the Gang of Four for the second time; the Tangshan earthquake happened with a quarter of a million people dying; Mao died; and then the Gang of Four was purged. So it was this momentous news year in China, but no American journalists could go into China, and there was almost no video. These were all radio, not TV, stories. And they happened just at the moment I had an opening as a radio stringer. So my first year, I cut my teeth on the biggest China stories in many, many years.

If you couldn’t actually get into China, how did you do the reporting?

We spent a lot of time going through the Chinese press. After the Tangshan earthquake, I went to the railway station at the Hong Kong border to see if I could find any eyewitnesses coming off the trains. The only video that existed was from the Cable and Wireless building in Hong Kong, which would record the Canton TV News at 7 p.m. and then make the video available. That’s how the pictures of Zhou Enlai’s funeral came out and how we covered Mao’s death. For me, it was this fantastic opportunity. Like so many journalistic careers, half of it is just being in the right place and shit happens.

CNN launched in 1980 and was a very fledgling organisation when you joined. What was the network like in those early days?

CNN was this sort of insane idea from Ted Turner. People would call it Chicken Noodle News. No one had heard of it, no one took it seriously. And, you know, the pay was abysmal, the hours were long, the benefits were negligible. But it was absolutely wonderful, because Ted Turner was committed to sort of revolutionising television news. Back then, the concept of twenty-four-hour news was unprecedented. It meant, first of all, that you could report something when it happened. You didn’t have to wait until six-thirty in the evening for the nightly news. The pressure was actually that we had to file something every day, because otherwise we would go to black.

I was the fourth foreign correspondent hired by CNN in early 1983, and they hired me as the “fireman correspondent”. They told me, “Your job is that when something happens anywhere in the world, we’re gonna put you on a plane.”

What was your first big story at CNN?

Initially I was based in London, but they said, “Before you get settled in London, would you mind doing some vacation relief for the guy in Beirut?” So off I went to Beirut. With my usual penchant for good or bad timing, within a month of my arrival, the Islamic Jihad blew up the American Embassy. It was the first big suicide terrorist attack. Then they did the same thing with the US Marine barracks later that year. I actually had an appointment at the embassy the morning it was blown up, but at the last minute decided to shoot a feature in south Beirut. We were driving on the seaside road, and I looked out the back window of the car and saw this huge plume of smoke. I said, “Something must have happened. Let’s turn around.” We got there and sixty-plus people died. I would have been in the embassy when the bomb went off. That was one of those what-if moments.

Did you have any other near death experiences?

I’ve been pretty lucky. In 1976 in Thailand, there were big protests against the military, and at a big rally some right-wing guy threw a grenade into the crowd and it rolled, came to a halt at my feet, but didn’t go off. So there have been a few moments.

Beirut was the first time I had really covered a serious war. Not only was there the Islamic Jihad, but the Israelis invaded Lebanon in 1982 and besieged Beirut. Then when the Israelis withdrew, the Druze and the Christians resumed their war. And so you had this situation where everybody was fighting everybody.

I stayed at the Commodore Hotel, which was the great journalists’ hotel in Beirut. The joke was, when you check in, they would say, “Do you want to room on the car bomb side of the hotel? Or the incoming artillery side of the hotel?” Literally, there were nights when I slept in the bathtub, because it protected against shrapnel.

How was TV news changing in the early 1980s?

The last year I was at a major network in Hong Kong—that was 1982 and by then I was at NBC—the whole bureau produced seven stories that made it on to NBC Nightly News. At CNN, in my first three months in Beirut, working alone with a cameraperson, I did a hundred stories, all of which got on the air. So while at the networks you had to fight for airtime, at CNN, you had to fight to let them give you a decent night’s sleep. From a reporter’s point of view, it was like paradise. In those early days of CNN, the mantra was, “We don’t have stars. The news is the star.”

When did you finally get posted to Beijing?

It was always understood that I would go once the CNN organisation was on a strong enough footing to open a bureau in China. It finally happened in 1987. We opened up this bureau with no resources. CNN, at that time, was super cheap. But the appetite for China stories was insatiable.

American audiences wanted to know what life in China was like. Nobody really cared who was up or down in the Politburo. One of the first stories we did was on an international makeup exhibition in Beijing. Dozens and dozens of young women were lining up to be made up. This was not long after the Cultural Revolution, when everybody wore blue and grey and makeup was considered bourgeois. People were desperate for change. And the government was overseeing this. So it was an extraordinarily lively, hopeful, exciting time.

You were one of the first reporters at Tiananmen, and in your new book you give a fascinating account of the relationship between news coverage and the historical impact of the protests. You claim that live coverage of Tiananmen occurred through an accident of history. In May 1989, China planned a summit with Mikhail Gorbachev, which represented a major rapprochement between China and the Soviet Union. China was eager for the international press to cover it, so, in an unprecedented move, they issued hundreds of journalist visas and allowed networks to set up live satellite feeds. It was this, you argue, that shaped the way we remember and think about the June Fourth massacre in Beijing.

Yes, it made a huge difference. In what way precisely, I don’t know. But you’re absolutely right. Compare it to Rangoon in 1988, where the Burmese generals crushed a popular uprising led by Aung San Suu Kyi in quite a bloody way. For that, there were hardly any TV cameras, and there was no live coverage. Granted Burma is a small country compared to China. But had there been wall-to-wall live coverage, that crackdown would be remembered differently. So yeah, Tiananmen was one of those funny things, where timing, coincidence and accidents shaped history in ways that people don’t really think about.

Remember, at that time, to do a live transmission from a remote location, you had to bring in a three-metre satellite dish and kilos and kilos of equipment. We got permission from the Chinese Communist Party to go live from the rostrum of Tiananmen, which is where they planned to have the welcoming ceremony for Gorbachev. But on the morning that Gorbachev arrived, when we looked down on Tiananmen, it was full of protesters. So those are the images we put on air for American audiences. Meanwhile, the Chinese leadership had to whisk Gorbachev in through the back door of the Great Hall of People. The humiliation level for the Chinese Communist Party and for Deng personally, you can’t discount how powerful that was. And the TV coverage magnified it.

You’ve written about this as the “CNN effect”, where live coverage forced politicians to react to events in real time. How did that come into play during Tiananmen?

In the midst of the Tiananmen crackdown, the US secretary of state, James Baker, came on CNN—again, it was an accident. The interview had been pre-booked before the army was ordered into Beijing. During the segment, they came to me for a live report, and I described the scene in Beijing. And then Charles Bierbauer, the host, said, “All right, Mr. Secretary, what’s American policy on this?”

In the US, the public reaction—what people saw—was so strong that the government had to use very tough language. They had to announce all kinds of sanctions. Nonetheless, President Bush, who had served as US envoy [to China in the 1970s], didn’t want to see the relationship go down the drain. He made concerted efforts to signal to the Chinese that, despite all this, he wanted to maintain the relationship. But there’s no question that in the absence of live coverage, you would probably have had a much more mild American reaction. And the degree to which public opinion and perceptions of China changed as people all over the world saw this, it can’t be underestimated.

So Tiananmen was a watershed moment for China but also for the media. It set the stage; for the first time, a crisis in a distant, previously not easily accessible country was covered live and therefore experienced in real time around the world. I know it put CNN on the map in a very big way. It also laid the groundwork for what then happened, in an even more dramatic way, in the first Gulf War, which I also ended up covering.

Tiananmen is one of many episodes in your new book, Assignment China, which pulls the curtain back on how journalists covered China for the better part of the last century. What were your goals for the book? What did you want to show through these oral histories?

There’s an old joke that the two things you don’t want to see the inside of are a sausage factory and a newsroom. And for the same reason—you don’t really want to know what goes into it. But in point of fact, that’s absolutely crucial. The fundamental premise of Assignment China is to show how most people got to know what they know about China: the process by which journalists gathered the news, the decisions they made about what stories to cover, who to talk to, what images to shoot and where to go. It talks about the challenges they faced on the political front—harassment, censorship, fights with their bosses, logistical problems of transmission, how you get your story out—and all of that affects the final product. It’s a very messy process.

You also have the fact that these stories are just intrinsically, extraordinarily interesting. What was it like to be the Associated Press correspondent in Nanjing in 1949 when the Red Army rolled in? What was it like sitting in Hong Kong in 1967, trying to figure out the Cultural Revolution? What was it like going to China on the press plane with Nixon in 1976? Or opening the first New York Times bureau in Beijing? Or covering the rise of China, or the Sichuan earthquake, or SARS, or Covid, or the rise of Xi Jinping?

I’ve always felt that the extent to which you can demystify what journalists do is good for journalists, and good for the product of journalism, because then the consumers of news have a somewhat more realistic idea of what’s involved. Especially today, when everybody has an opinion about the media. The media does this. The media says that. The media has an agenda. The media is biased. The media is anti-China. The reality is it simply doesn’t work that way. And if people can come away from this book with more of a sense of how it does work, then I feel it’ll have made some contribution to public understanding.

![]()

- Tags: China, David Frazier, Free to read, Hong Kong, Issue 33, Mike Chinoy