There’s a wall in east London where the traumas of Hong Kong’s exiles have been playing out in microcosm. In early August, a student artist from China stencilled on it, in large red characters, the twelve core values of the Chinese Communist Party—including prosperity, patriotism and harmony. It may have been satirical, but on Chinese social media, some nationalist users praised the projection of the party’s values overseas. Soon, the characters were covered over with stickers calling Xi Jinping a dictator and with graffiti reading: Free Tibet, Free Xinjiang, Free Hong Kong. On social media, Little Pinks—aggressive online patriots—raged against the defacement.

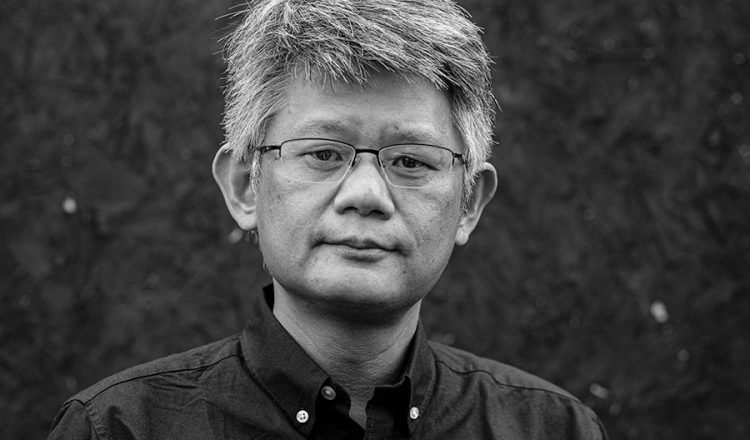

Back in Hong Kong, Christopher Mung’s face has also been appearing on walls in black and white. In July, the authorities put Mung—one of the city’s best-known labour campaigners—on a list with seven other activists, politicians and scholars, offering bounties of HK$1 million (US$128,000) for information leading to their arrests. All of them had long since left Hong Kong for the US, UK, Canada or Australia. They were, in theory, out of reach of the Chinese government, but the authorities nonetheless put up wanted posters around Hong Kong.

The warrants are, Mung says, a sign of how the Chinese government is trying to extend its rule far beyond its borders, and to apply its draconian national security law—which effectively criminalises most forms of dissent in Hong Kong—to people living beyond its immediate reach.

- Tags: Christopher Mung, Hong Kong, Issue 33, Peter Guest