The junta’s guns were aimed at the streets. But much of the resistance had already gone digital—anti-coup messages disguised and snuck into memes, lyrics and profile pictures coordinated by unlikely strategists.

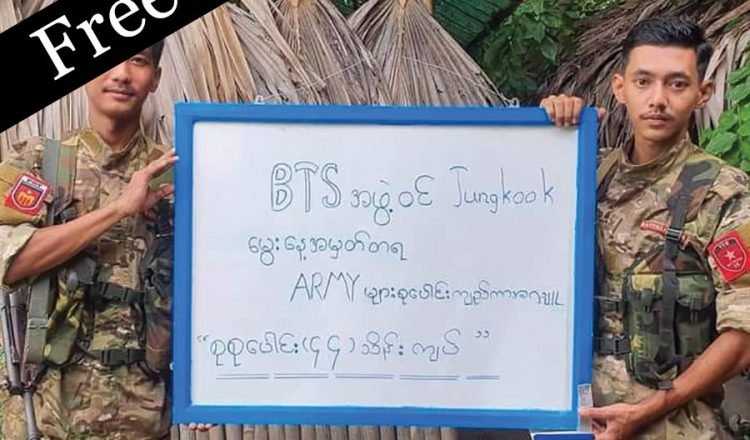

When Myanmar’s military seized power in February 2021, they likely didn’t anticipate having to deal with people who spent their days celebrating pop idols. But the country’s K-pop loving citizens, such as those who belong to fandoms like ARMY—the collective name for fans of the popular Korean boy group BTS, wherever they might be in the world—quickly switched from adoring their perfectly coiffed superstars to fighting a literal military.

As the tanks rolled into Naypyidaw, another kind of mobilisation began taking place online. Fan pages that typically organised birthday fundraisers for K-pop idols started raising money for displaced families and anti-junta protesters. Skills and networks usually reserved for coordinating music-streaming activities (to boost the sales and rankings of favourite groups on charts and music shows) were deployed to organise mutual aid efforts. As the people of Myanmar rose to protest the assault on their fledgling democracy, fans began doing what they know best: create, collaborate, organise. What has emerged is an extensive, subtle and quietly effective network of resistance driven by youthful, decentralised and digitally fluent fandom communities.

Some of us joined because we couldn’t march,” Phoo (not their real name) tells us. “We were too young or too afraid or too far away. But inside [the] fandom, we found purpose. We found healing. We were no longer powerless spectators, we were participants. And in helping others, we found ourselves.”

Administrators of fan pages have become frontline resistance leaders, raising funds and launching digital campaigns. Multiple online platforms are put to use: Facebook is the main space for domestic coordination and connecting with like-minded people. With its hashtags, X (formerly Twitter) has emerged as a practical channel for drawing international attention to what’s happening on the ground in Myanmar. On TikTok, political messaging gets snuck into trendy shortform videos that educate as they entertain, while Telegram is used for activities that don’t need to be published to a wide audience. YouTube serves as a source of income; fan-generated content is monetised and used to finance everything from protest supplies to assistance for internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Of course, these people have never stopped being fans; they’ve simply expanded the scope of their activity and attention. Activism isn’t seen as a divergence from fandom—just an extension of it. Now, idol birthdays are celebrated with fundraisers for IDP camps. Fan fiction has evolved into political parables, while fan art carries messages of courage, resistance and hope. Leveraging the way outsiders see them as “just fans”—and therefore easily dismissed or overlooked—people build networks under the radar. As the state endeavours to suppress dissent online, fans create new hashtags to replace banned ones, concealing messages in plain sight and working collectively to manipulate algorithms and drown out state propaganda.

In a 2021 interview with the tech-focused news website Rest of World, Kay Zin, then just nineteen years old, described how she and her friends taught people how to use Twitter, encouraged them to use hashtags like “#WhatsHappeningInMyanmar” and organised “mass trending parties, where we call on our followers to tweet about a certain issue at a certain time”.

“Most of our followers are 16- to 21-year-old fangirls and fanboys who follow K-pop bands like EXO and BTS and idols like Sehun, Chanyeol, and Jungkook,” Kay Zin said. “Before the coup, people mocked K-pop fans, but now we’re the ones actively taking part in online activism.”

This is all risky work. People can be detained for speaking out on social media, and posts constantly disappear as people grow afraid of doxxing and state retaliation. Some fandom pages have vanished overnight; others see their page admins arrested by state forces. Security considerations underpin the foundation of fandom action: people use VPNs and pseudonyms, encrypt their chats and purge their phones after online campaigns. Fandoms, previously propelled by a shared love for a pop star or group, are now driven by the need for survival. And survival means resistance.

How does one shut down a fandom? It has no hierarchy; there’s no clear leader to be arrested, detained or killed. Fandoms can move quickly, unburdened by bureaucracy. There’s no need for consensus, only momentum—which, in today’s digital age, can be generated by a single viral post. Things can get done as long as enough people are willing to participate. Unlike formal political parties, armed groups or organisations, fandoms are amorphous and anonymous, able to form and re-form around attempts to suppress them.

Belonging to such a group can be a lifeline in dark times. At its core, fandom is about emotion—shared, amplified and performed. It’s not only about parasocial relationships with celebrities but also about feeling a connection to fellow fans. And when the weight of the coup and the state of the country becomes unbearable, fans in Myanmar can find solace in one another.

Although some local celebrities—such as Daung, an actor, and Paing Takhon, a model and actor—publicly supported the anti-coup movement, most of the international celebrities these young fans admire have never made any public statement about the situation in Myanmar. This is nothing new: K-pop idols typically steer clear of anything overtly political or potentially controversial. As Gi-Wook Shin, Haley M. Gordon and Maleah Webster of the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center observed in a commentary for The Diplomat: “K-pop idols’ silence is particularly conspicuous in comparison to their global fanbase, which has proved to be a formidable source of human rights advocacy around the world.”

The stars themselves might be silent—and possibly not even very aware of Myanmar’s political crisis and conflict—but there’s already plenty of material out there for fans to make meaning for themselves. Myanmar ARMY have interpreted BTS’s “Love Yourself” concept—communicated via album titles, song lyrics and even a global campaign in collaboration with UNICEF—as a call for self-preservation and courage in a time of national crisis. As people experience burn out, depression and anxiety, other fans within the community are providing a space of safety and understanding. Phrases like “you are not alone” and “we are still here” are frequently shared within fandom circles. Emotional labour, like digital work, is crowdsourced. There’s always someone online, someone listening.

Apart from safety, though, the shapeless, decentralised nature of fandoms can pose their own challenges. The movement can feel fragile and under constant threat from mass reporting campaigns led by military supporters. Things flow wherever and whenever online attention is harnessed—while this spontaneity can be a strength, the lack of centralised leadership also means that long-term sustainability and strategy is difficult, perhaps impossible, to achieve.

The fandoms active in Myanmar are diverse: while some support a group as a whole, others zero in on specific members. Even during these tough times, fandoms regularly plan events to honour their idols’ milestones—album releases, birthdays, debut anniversaries, among others. These events can be very effective in directing people’s attention—and money—toward making meaningful contributions. The impact of such action, still ongoing four years after the coup, is difficult to study and quantify. But there are some data points, and these numbers tell their own story. Through diverse campaigns, ARMY in Myanmar has, by early 2024, reportedly raised a remarkable 1 billion kyat (US$476,190) for the resistance. Hailangs—fans of Huang Zitao, a Chinese rapper and former member of the K-pop group EXO—raised more than 40 million kyat (US$19,047) for IDPs and ethnic resistance forces. BLINKs—fans of the Korean girl group BLACKPINK—planned a sizable fundraising drive, resulting in concrete contributions to humanitarian and anti-coup causes: food sent to IDP camps, medical supplies for the nationwide Civil Disobedience Movement and even resources for resistance fighters.

In a country suffocated by fear and violence, fandoms have become spaces of expression and empowerment. In a world that often overlooks the power of young people online, fan communities have emerged as an unseen engine of revolution in Myanmar. This is not resistance as commonly understood, but it’s a story of how joy turned into defiance. It’s an example of how being part of a community—however it’s organised—can empower people to do more together than they could ever have achieved alone. As a K-pop fan tells us: “We didn’t choose this war. But we chose each other.”

![]()

[/wcm_restrict]

- Tags: Free to read, Htaike, Issue 40, Myanmar, Nway