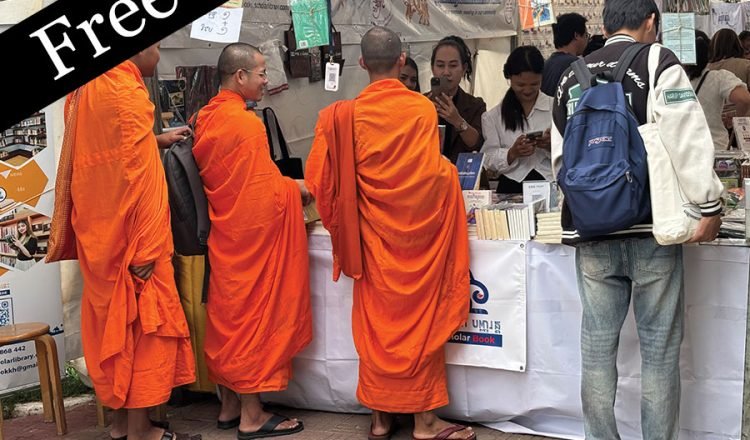

It’s busy at the 11th Cambodia Book Fair. Over four days in December, outside a convention centre in Phnom Penh, visitors throng the aisles in hopes of finding a favourite title or meeting a writer. The vibe is decidedly upbeat.

Romance and fantasy books seem especially popular. Twenty-six-year-old Chea Seng Iy keeps getting interrupted as gaggles of teenage girls arrive for selfies or an autographed copy of her first novel, Zoom Zone.

“Like ‘friend zone’, ‘lover zone’, ‘ex zone’,” she says, explaining the book’s interlocking stories of three high school couples in her hometown of Sihanoukville. “It’s my first book and it may be the last one, writing it was so hard!”

At the Phnom Penh Used Books stall, twenty-one-year-old Borney Sok and her friends try to interest a visitor in purchasing a “blind date”—a secret book wrapped in brown paper—for US$6.99. “[In Cambodia] a new book is US$12 to US$14, so it’s a big discount,” she says, hopefully pitching their gently read collection of classics. “You find some pretty good ones!”

But the longest queues form at the tables of up-and-coming Khmer publishing houses like Seavphovjivet (The Book of Life), which was launched in 2018 and now carries thirty-five titles. Thavry Thon, its founder, proudly surveys the scene as young readers wait their turn to buy a book—perhaps even Storm, which she co-wrote with the famed Cambodian writer Mao “Rabbit” Samnang.

“Wow, she’s already finished my book,” Thon whispers as she hands an autographed copy of her latest volume back to a starry-eyed young customer. “This one is my very first time writing in the third person as a novel. I’m so happy we did this!”

She might be the boss, but at such moments Thon can’t help bubbling over with the enthusiasm of a writer who, not so very long ago, was herself a young reader with a dream.

Photo: Tom Marshall

Thon was born on Koh Ksach Tonlea, an island forty kilometres south of Phnom Penh, in 1989. That was the year Vietnam finally left after a decade-long occupation in the People’s Republic of Kampuchea. Ten years after the end of their genocidal rule, the Khmer Rouge were still armed and holding ground on the Thai border, with active fighting continuing for most of the coming decade. Times were hard.

Thon tells the story of how she got her start in her memoir, A Proper Woman. Her first job was to haul buckets of water from the Bassac River and gather firewood to boil it. As a grade school student she collected tamarind leaves after morning classes, harvested peanuts for US$1.75 a day during the holidays and carried loads of guava on her bicycle to sell at the school gates. Other kids teased her for being so poor, but she didn’t care. She was willing to do anything to keep going to school.

Thon’s mother grew vegetables, tended pigs and converted meagre profits into small bits of gold that could be hidden away for future use. Her father—one of the lucky ones who returned unscathed after being pressed into service as a child soldier for the Khmer Rouge—ran an ad hoc ferry service and farmed for long hours on distant plots. Everyone worked all the time, but there was never any question about whether Thon and her brothers would stay in school.

As Thon grew older, many of her female classmates—the ones whose families didn’t see the point of all that learning, the ones who teased her the most—were plucked out of school to help on family farms. Her own grandfather urged their family to do the same or maybe even send her to work in a garment factory until she could be married off. That was what proper Cambodian girls were supposed to do.

Thon had different ideas. She dreamed of travelling to distant lands on one of those airplanes that soared high above the village. She dreamed of becoming a writer of books that people would love to read. Surely that wasn’t too much for a young girl from a tiny island to ask?

Seavphovjivet’s office has the feel of a thriving family business. Several employees scurry around managing invoices and checking shipments of books piled up near the front door. Thon’s husband, Tomas Hanak, who manages the company’s finances, carries their firstborn son with one arm while peering at his computer monitor.

Everyone pitches in. Thon’s older brother, Rithy, is off coding somewhere or holding meetings downtown. Some of the publishing house’s start-up capital came from his success as founder of Koompi, Cambodia’s first personal computer. Thon’s mother keeps everyone fed during the busy book fair season. Her father, wiry and strong, slips into the room to lend a hand with the baby. He’ll soon be heading back to the village—it’s a ninety-minute ride on a tuk-tuk—where there’s always more work to be done.

These days, Thon’s energies are balanced between the thrill of writing—inspiring and motivating readers with works that feature trailblazing young Cambodian women—and running the business. Much has changed since Seavphovjivet’s first books were published in 2018. Back then, publishers didn’t pay much attention to the physical quality of their books and bootleg copies were everywhere. “I saw the market, it was there,” Thon says. “I’m a writer, too. I’m not happy if someone steals my work.”

Piracy wasn’t the only problem. Back in 2018, Cambodian booksellers had no shelf space and even less patience for homegrown authors. Thon often got blank stares from bookstore owners; once, she had to haggle with a store for a simple payment on books sold. Today, there’s a thriving Khmer-language section at the big Kinokuniya bookstore downtown and doors are flying open for Thon and her writers. Their books can be found all across the country, and free copies of the Khmer edition of A Proper Woman are distributed to NGOs, prisons and schools. One copy was spotted on a classroom shelf in remote Varin High School in the north of the country, closer to Thailand than Phnom Penh.

Of course there are worries. The company has been bracing itself for the possibility of getting entangled in a US–China trade war and the likelihood of an economic slowdown. Tomas plans to print fewer books next year and keep a bit more cash on hand, just in case. But Thon has faith in her readers. She shares a recent Facebook post from a fan: “I have the courage to speak to you because I read your book.”

Riem Sokchamroeun, a first-time author who recently published a memoir of her battle with breast cancer, says Thon helped her find her voice. She has since been overwhelmed with requests for interviews and speaking engagements. “This kind of book, my journey, we can say it’s the first one in Cambodia,” she says, describing the stigma around discussing cancer publicly. “People stay quiet.”

Back at the book fair, it’s clear that many readers and their families have arrived with titles in mind and money to spend. One of them is twenty-five-year-old Pich Kanha, who has come solely to meet her hero, Thavry Thon, and buy her latest book.

Kanha moved to Phnom Penh to live with her sister when she was just ten years old. She managed to earn money, finish school and find a job as an assistant in an architecture firm. But she felt desperately alone. Thon’s coming-of-age story in A Proper Woman gave her courage. “It was the first book I found that really inspired me,” she says of Thon’s memoir.

Rithy Phoung, twenty-one, is a Book Fair worker who has started exploring titles on leadership and motivation. He says he’s finding his groove. “When I was young, I thought reading was very boring. Now I’m finding my flavours. Once you find your flavours, you read more.”

The rapid development of the Cambodian publishing industry is a sight to behold for Sothik Hok, vice-president of the National Book Fair’s organising committee. “When we started in 2011, we had around ten booths and there were maybe five publishers,” he recalls. Now there are nearly 300 booths and 160,000 visitors, and Cambodia has at least fifty publishers that meet professional standards for editing and production, he says. It’s still a fledgling, fragile industry, but it’s growing fast.

Hok is hopeful for the future. There’s still a lack of public libraries in Cambodia, but half of all primary schools in the country now have at least a small one. The reading-focused SIPAR organisation, of which Hok is director, even sets up a popular mobile library right in front of the National Palace on weekends.

“We have to develop the reading habit in Cambodian society, especially in the middle class,” he says. “You have to start very young, build a culture of reading and encourage people to buy books for other people, children and the community.”

This fits right in with Thon’s plans: “In the next five years we want to focus more on the children’s market, because our readers are becoming parents.”

For many people in Cambodia, reading for leisure—let alone buying a book—is still considered a luxury, a non-essential part of the daily struggle of life. But reader by reader and page by page, that is starting to change.

![]()

- Tags: Cambodia, Free to read, Issue 39, Tom Marshall