Welcome to the Mekong Review Weekly, our weekly musing on politics, arts, culture and anything else to have caught our attention in the previous seven days. We welcome submissions and ideas and look forward to sparking lively discussions.

Mekong Review Weekly will be on hiatus until next year while we revamp our design. We’d like to thank our readers for their support.

To sign up for the newsletter, click here

c

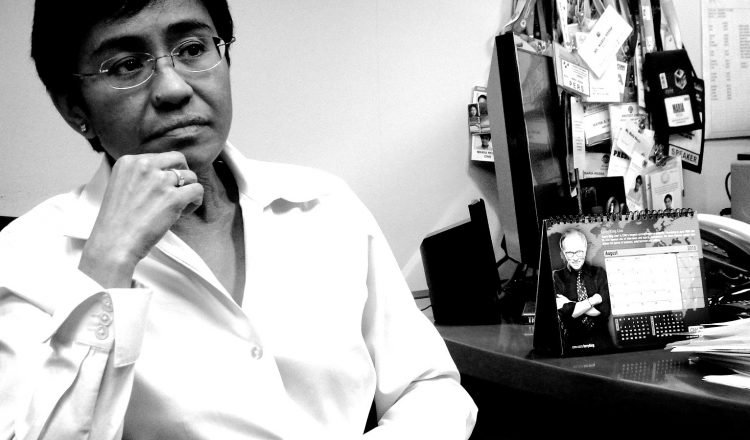

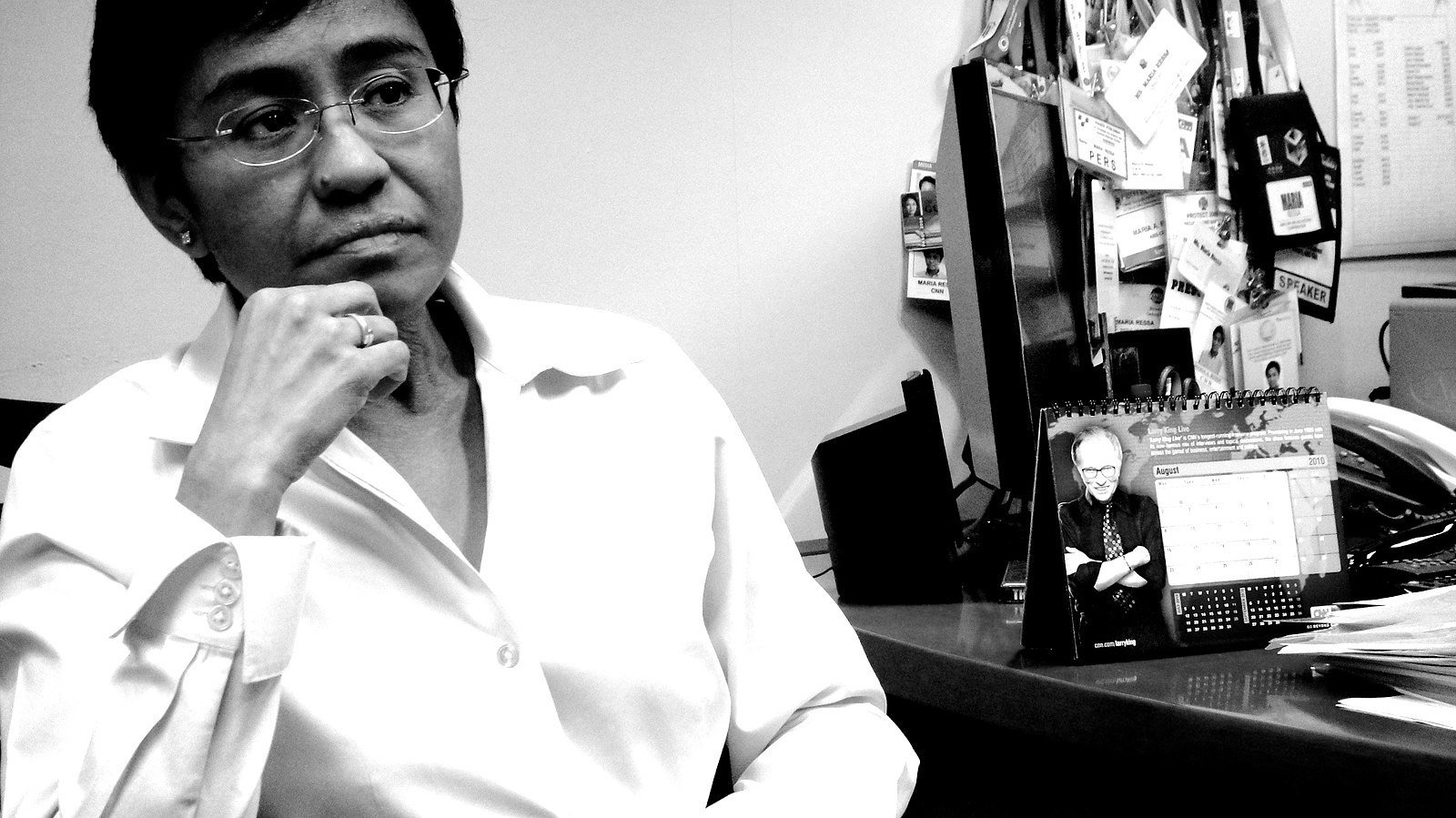

Courage under fire

Maria Ressa, Filipino-American journalist and author, made history last week when she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize along with Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov ‘for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression.’ For decades, Ressa’s hard-hitting investigations have won her accolades and enemies. The online news site Rappler—co-founded by Ressa and launched in 2012—has become among the most ardent defenders of press freedom in Southeast Asia.

Ever since President Rodrigo Duterte took office in 2016, Rappler has been relentless in exposing the depths of government malfeasance. Their work on Duterte’s ‘war on drugs’, which has resulted in thousands of extrajudicial killings, has been particularly hard-hitting. For this, both Ressa and her publication have become prime targets.

Rappler has kept a running tally of cases against them: as of August, there were seven open cases and more than a dozen prior cases. In a welcome development, two cyberlibel charges have been dismissed in recent months. But the clouds hang heavy. Ressa is appealing a 2020 cyberlibel conviction and if the case is not overturned, she faces up to six years in prison—still more if the other cases result in convictions.

The attacks against press freedom in the Philippines mirror that across the region, which saw a steep decline in the latest World Press Freedom Index. While the situation is most dire in Myanmar, post-coup, and in Hong Kong, following the draconian national security law, countries across Asia have followed a larger global trend of worsening repression.

Still, Ressa maintains in an interview with Rappler that ‘there is no better time to be a journalist. The times when it is most dangerous are the times when it is most important. So this is the best time to be a journalist, if you’re just starting out. Journalism will test you, mentally, intellectually, physically, spiritually, morally—you learn to draw the lines.’

In our forthcoming November issue, author Richard Heydarian reviews a new book on the Duterte phenomenon. We spoke with him about Ressa, Rappler and what this win means in light of domestic and international political realities.

Duterte has been an outspoken critic of the media, with his supporters often following suit. Can I ask how news of this prize has been received in the Philippines?

The fact that it went to journalists—one from Russia, one from the Philippines, two of the most dangerous places for journalists—says a lot about growing international recognition of the distinct threats posed to reporters and free thinkers in general across the world, especially amid the upsurge in authoritarian populism as well as a democratic recession across the world. In the case of Ressa, she was also one of the journalists who was a Time Magazine Person of the Year, along with the late Jamal Khashoggi. So I think this issue of journalists under threat has been captured in the global imagination for a few years and Ressa has been very much front and centre as far as this is concerned.

Nonetheless, the Nobel Peace Prize has not garnered the kind of reaction that maybe a lot of people were expecting, especially those partial to Ressa and appreciative of her indomitable and courageous work as one of the upholders of democracy in the Philippines.

There are a number of issues. First of all, Duterte remains popular, so critics getting awards doesn’t necessarily sit well with a lot of supporters of the president. Second, as far as Ressa is concerned, she hasn’t necessarily had the best relationship with a lot of people in the Philippine media. So there were tensions throughout the years.

Rappler consciously presents itself as a maverick start-up media company, which is upending a supposedly not-so-dynamic media landscape. But, obviously, as far as the Philippines is concerned, Rappler is just one of many platforms, and is not even the biggest platform, when it comes to calling out the excesses of the Duterte administration. ABS-CBN, once the biggest media network in the country—shut down last year by Duterte allies—had been at the forefront of shedding light on extrajudicial killings and all sorts of abuses and misuses of power by the Duterte administration. So there’s also this sense that that award, yes it’s supposed to be a recognition of journalists’ contributions, did not create the kind of upsurge of support and solidarity that it should have.

Do you see the prize lending any extra layers of protection for Ressa or Rappler? Is this likely to result in some of the cases against them being dropped?

As far as Ressa is concerned, they have been facing tremendous amounts of legal and online harassment. But the kind of threats they have been facing are not necessarily the kind of threats that journalists in Russia are facing. Journalists, even in big cities, are just being murdered there. That hasn’t been the case, thankfully, in the Philippines. And as far as the Duterte administration is concerned, while it has overseen networks of disinformation, while it has incarcerated a former senator for criticising its drug war, the kind of repression of the mainstream media, especially in major cities like Manila, is not comparable to what we see in places like Russia, or even in places like Turkey, and definitely like what we see in authoritarian systems like China. So I think that’s the context we have to keep in mind here..

This is the first time in 86 years that journalists have received a Nobel Peace Prize; what does this prize say about the current state of democracy?

The timing of the award is good because the Philippines is preparing for the next elections and there’s growing disillusionment with Duterte’s mismanagement of Covid-19, there have been corruption scandals left and right. So Duterte’s popularity has been on the wane. He had a 21-point decline since last year. But since his approval rating has been so high, he’s still enjoying majority support. That may change in the coming months as Duterte becomes a lame duck and people become more hopeful about a new kind of governance.

We see the opposition is rebranding itself, rebooting liberal politics. We see centrist candidates, charismatic candidates also coming out and criticising Duterte, even if they used to have good relationships with Duterte. And the prospect of a Marcos presidency next year, under Ferdinand Marcos Jr, has also riled up and mobilised sections of civil society and the opposition. So I think Ressa’s Nobel Prize, the first by a Filipina, kind of plays into the broader landscape of shifting tide against Duterte and also growing mobilisation and sense of urgency on the part of the opposition and centrists who are not necessarily just worried about another Duterte winning the presidency, in this case Sara Duterte or any Duterte successor, but potentially another Marcos winning the presidency.

In memoriam

The writer retires

Peter Zinoman

This story came to mind in reading Unruly Waters, Sunil Amrith’s ambitious and absorbing study on the importance of water in shaping Asia’s past, enabling its present and threatening its future. Despite the centrality of rains, rivers, coasts and seas in the region, water — hiding in plain sight, as it were — until relatively recently has received little sustained attention from scholars, who have more or less taken it for granted or subsumed its consideration under other topics, agriculture, most notably. It is unlikely that scholars or anyone else will do either of these things again, for among Amrith’s many accomplishments is to make crystal clear the case for water’s importance.

Read more here

Call me Ant

Sunisa Manning

When Anthony Veasna So’s story collection Afterparties debuts, or on the 100-day anniversary of his passing, or on his birthday, I will sit with Anthony’s work and let his voice come alive again. But right now I couldn’t stand it: such vibrancy might deceive me into thinking that this has been a grotesque misunderstanding. Whenever it is that we are able to emerge from isolation, I will find it hard not to go to his building, not to haunt Mission Dolores, not to scroll through his social feeds, unbelieving once again.

With his loss, the title of his short story collection, Afterparties, has taken on a grim double entendre. It would be like Ant to throw his own afterparty, wherever we go when we leave this realm. He feels near. I have almost texted him. I have the feeling he’s watching our grief. I can imagine him giving his droll sideways grin, saying: LOL, I thought you’d send bigger flowers. It would be very like Anthony to post selfies from the other side. It’s not so bad, he’d say. Your skin’s amazing here.

Read more here

Check it out:

The recently launched Queer Indonesia Archive has been amassing a treasure trove of photographs, magazines, films and more ‘reflecting the lives and experiences of queer Indonesia.’ Volunteer-run, the project aims to digitise and catalogue everything from oral histories to blogs. At a moment when LGBTQ+ rights are under threat, QIA looks to be a critical historical corrective. Check out the archive and learn more here.

![]()

- Tags: Newsletter